In the summer of 1955, Mamie Till lived what could be described as a classic American life in the predominantly African-American South Side of Chicago. She lived with her son Emmett, who was 14 years old at the time. Family had always been important to Till, and she hoped to use the summer to reconnect with relatives in Nebraska.

She wanted Emmett to join her, but he insisted on visiting his cousins in his mother’s native Mississippi. Till relented and saw her son off on a train to Mississippi. When Emmett said goodbye to his mother, his youthful face was healthy and full of life and potential.

He returned to her in a casket.

Emmett had been brutally tortured and murdered. His crime: reportedly flirting with a white woman. For this, two white men abducted Emmett from his uncle’s home in the dead of night to send a distinct message to Emmett and other African-Americans who dared forget their place in American society.

They beat him, dragged his bruised and bloodied body across the ground, and then shot him in the head. As if their actions had not been disgusting enough, the two men then bound Emmett to a metal fan and tossed his body into the Tallahatchie River.

Emmett’s body was discovered days later, mutilated almost beyond recognition. His uncle was only able to positively identify Emmett thanks to the ring he wore, engraved with his father’s initials. His mother had given him the ring, just the day before his departure.

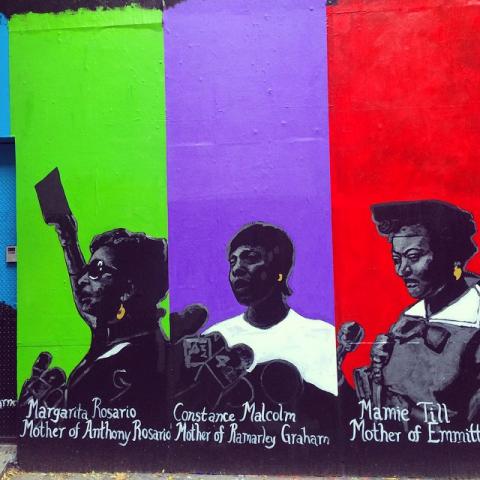

In a stunning act of defiance, Mamie Till chose to leave her son’s casket open during his funeral, which she insisted on making open to the public, and to leave it on display for five days. With the emotion of a grieving mother, Till said she wanted to “let the world see what has happened.” The world responded to her call: tens of thousands came to view Emmett’s casket, and pictures of his brutalized body ran in Black newspapers across the country.

With the acquittal of her son’s murderers in September 1955, Till’s dreams of justice for Emmett died. At the same time, a lifelong passion for racial justice was born within her.

If Emmett’s murder galvanized the civil rights movement, then Mamie Till became one of its most public faces. She tirelessly toured the country with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), using her son’s story to bring attention to racial injustice nationwide. Motivated by the memory of her son, she began working with children, encouraging them to view the world with love, not hate. She gave interviews about her son over the course of four decades in order to bring the message of racial justice to a wider audience.

“People really didn’t know that things this horrible could take place,” Till lamented. Thanks to one mother’s efforts, the burgeoning movement for more robust civil rights was brought into the homes of thousands of previously unaware Americans.

Decades later, the extreme, extrajudicial brutality Emmett Till encountered is almost inconceivable. Nevertheless, violence against African-American bodies still takes place today, sustained by a criminal justice system that provides everything but justice. And mothers like Mamie Till are still at the forefront of the fight for justice for their children and all children.

In the early 2000s, Tarsha Jackson, much like Mamie Till, lived in a loving home with her children in the suburbs of Houston, Texas.

At age 10, Tarsha Jackson’s special needs son, Marquieth, was arrested on a ridiculous charge: breaking a $50 window.

Marquieth was kept for nine months in a juvenile detention center until he was ultimately transferred to the Texas Youth Commission. Marquieth was incarcerated for three years and six months in the Texas Youth Commission, during which he was physically, sexually, and verbally abused.

He was only 11.

Though Marquieth ultimately fared better than Emmett Till, his case is also heartbreaking. His arrest was entirely legal, undertaken by those explicitly tasked with protecting children like Marquieth: the police. The maltreatment he suffered during incarceration was committed by a system supposedly interested in his well-being.

The justice system failed Marquieth just like it failed Emmett Till.

In this failure, Tarsha Jackson, like Mamie Till before her, found an opportunity to ignite change.

Jackson became one of the most visible faces fighting for the reform of the juvenile justice system in Texas, eventually directing Texas Families of Incarcerated Youth (TFIY), a family-based juvenile justice advocacy organization.

Under her leadership, TFIY gathered other concerned mothers to lobby passionately the Texas state Legislature. These efforts culminated in various legislative successes, including a prohibition on sending juveniles to detention facilities for Class C (or low level) misdemeanors and an unprecedented Parents Bill of Rights.

In her current capacity as the Harris County Director for the Texas Organizing Project, Jackson leads the effort to advance juvenile justice reform through direct action, grassroots lobbying, and electoral organizing.

Jackson is one of a growing number of family members nationwide, mostly mothers, who have taken up the mantle to advocate for juvenile justice reform, one of the most pressing issues of our time.

Their work has been chronicled in a new report from the Institute for Policy Studies entitled “Mothers at the Gate: How a Powerful Family Movement Is Transforming the Juvenile Justice System.”

These mothers are carrying the flag that Mamie Till held high, using their status as mothers to guide their activism and engage the hearts of others.

When reflecting on the circumstances of her son’s death, Till said simply but profoundly, “I realized that this was a load that I was going to have to carry.”

Today, mothers like Tarsha Jackson, struck by their own personal tragedies, are not only carrying their loads, but working to ensure that other mothers never have to.

Ebony Slaughter-Johnson is an intern for the Criminalization of Poverty Project at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Spread the word