Of the 2 million working-class voters the country’s largest labor union plans to persuade this presidential election, a quarter will come from Ohio.

With outsized influence in picking presidents, which can be measured in the flood of political activity and outside interest, Ohio has attracted an army of trained canvassers who will pound the pavement in mostly white, blue collar neighborhoods across the state.

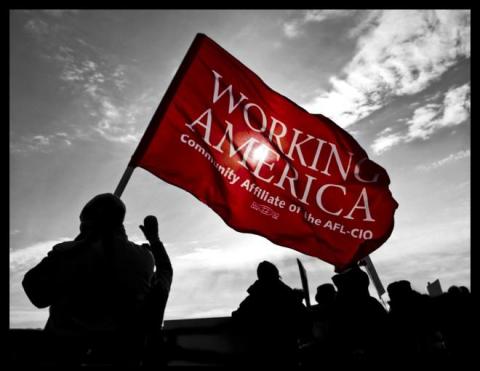

Some 70 canvassers in Ohio will likely triple by Election Day as Working for America, an organizing group focused on empowering non-unionized workers, seeks to understand and harness economic concern to tip the election for Democrats.

The effort is funded by the rank-and-file membership of the nation’s largest umbrella union group, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (or AFL–CIO), and about 1 million Ohioans. Over the past 12 years, the labor group has held repeat conversations on their front porches to advance progressive policies and candidates.

The group gathers data from the intimate interactions, held year-round in Ohio and elsewhere. The data snowballs with each election and issue campaign, giving the organization’s analysts a sense of where to send canvassers and what to talk about.

While candidates and political parties use mostly volunteers to get the public to help them optimize ad spending, Working America aims to shape attitudes in face-to-face conversations, usually standing on a front stoop with a cracked screen door or a barking dog between a canvasser and a malleable voter.

Capturing minds

Working America canvassers, who make $15 an hour after 90 days, show up at a headquarters in either Cleveland, Columbus or Cincinnati at 1 p.m. for daily eight-hour shifts, which include dinner time when laborers are likely to be home.

Trained and guided, they drive in any direction for up to 90 minutes. This puts their reach in northern Ohio from the outskirts of Toledo to Youngstown and Canton. Previous campaigns included rural southeastern Ohio, where Republicans — knowing Donald Trump did well there in the primary — are deploying their own canvassers to exploit the conservative tilt of coal-country Democrats.

On a recent afternoon in June, Cleveland resident Soren Norris, who normally trains Working America canvassers, displayed his power of persuasion for a reporter who tagged along in Cuyahoga Falls.

White voters, some retired and most of moderate income, opened doors in a row of well-maintained Cape Cod homes. The neighborhood is a vestige of the middle class life.

At one house a dog — riled by the knocking — bit its Trump-supporting owner. The woman will not likely receive a return visit as Norris failed to shake her support of Trump.

Neighbor Caleb Parker will. The small aircraft mechanic supported Gov. John Kasich in Ohio’s Republican primary. He usually votes Republican.

But Parker, 40, resents Trump’s condemnation of Muslims, though he supports a temporary halt on immigration and respects the billionaire’s business acumen.

“I’ve always thought America should be run like a business, long before I thought of Donald Trump,” said Parker, who said he weathered the recent recession better than most.

A stalwart Republican voter, he doesn’t “like what the Democratic Party has planned for socialism, especially with health care … But I am still torn,” he added. “I guess what I’m saying is I’m supporting the Republican Party and Trump is most likely going to get nominated to represent it. But I’m still not happy with what he has to say. I am happy with his success as a businessman.”

Conversations count

Working America Deputy Director Matt Morrison said the group relies on a “mountain of data” to shape its plans.

“And and in Ohio specifically, we know unequivocally that if you want to change voter turnout in a certain way — dollar for dollar, pound for pound — the best way to do that is to go door to door and have face-to-face conversations,” he said.

Morrison built the road map of voters for canvassers to follow. They travel to working-class neighborhoods with more than 90 percent white residents. Household incomes are below $75,000. And they turn out big for the swing state’s elections, based on past results.

In 2012, when Working America’s Ohio operation was a third its current size, these battleground voters represented nearly 49 percent of ballots cast, Morrison figured.

“We won’t be that far off that year,” he said of 2016. “When you have a cohort that large, you must have a clear understanding of what is driving their economic behavior.”

Disappearing dream

Gauging economic angst fuels each conversation. Ancillary concerns aren’t disregarded. They’re redirected to favor a pro-labor solution.

Canvassers ask how the recession of 2008-2009 impacted each life, who’s to blame for it and which candidate is best suited to increase wages and continue job growth.

Responses vary. But most talk personally about a middle class squeeze and a disappearing American Dream.

Opening his front door, James LaPlant explained that after graduating with a criminal justice degree from Kent State in 2009, he entered the college’s police academy with optimism.

Some of his professors had helped launch the local academy two years before, when job prospects for police officers were as good as they are today.

LaPlant, and others at the time, were less fortunate.

Police departments from Mahoning to Summit County, where LaPlant applied, trimmed low seniority officers. Those who remained had higher salaries that strained budgets when, as the staffing demanded, they worked overtime. Plus, veteran officers stayed longer on the force to nurse their recession-ridden retirement accounts back to health.

As the first of his three children was born a year later, LaPlant decided to go back for an accounting degree. Now 32, crunching numbers and looking to purchase a first family home this summer, LaPlant said there’s “too many fingers to point” at who’s to blame for the recession.

The son of a factory worker and farming pipe-fitter, LaPlant’s generation has less buying power than his parents’.

“I think the American Dream today is just making enough to support your family for the majority of the country,” he said. “The middle class is pretty much gone.”

LaPlant opposes Trump as much as his Bernie Sanders-supporting wife.

“Dude, you’re on board,” Norris, the canvasser, said after listening quietly.

Between now and November, another Working America employee will return to LaPlant’s front porch and ask him to visualize Election Day: when and where will he vote, what he’ll eat for breakfast? “Plan-making,” as the psychological tactic is called, increases the chances that a would-be voter actually does.

Tough times

Some conversations are painful.

Kathy Cutlip, a retired teaching aide in Medina City Schools, moved with her husband to Cuyahoga Falls last year, buying a home well below its appraised price. Relocating offered a retirement closer to their daughter. Limiting their options, though, was life after losing $200,000 in savings when the stock market crashed.

“We had investments that went down the tubes,” said Cutlip, who reckoned the couple’s diversified investment portfolio suffered less than others.

Norris tapped Cutlip’s concerns into his iPad, shielded from the rain by a Ziploc bag. Scanning the next home on his list, he can see who lives there, how many times Working America has visited before and even what was discovered each time.

Norris considered the stories he’s heard when asking people to open up instead of picking from a list of pre-selected concerns.

“It’s pretty powerful,” said Norris, who worked in Ohio on Senate Bill 5, the failed 2010 gubernatorial re-election of Ted Strickland, Barack Obama’s two presidential campaigns and labor issues, like raising the minimum wage in communities from Anchorage, Alaska, to West Philadelphia.

“I’ve been doing this for a while,” he continued. “People sometimes open up and start crying on the porch. This is more powerful than a TV ad.”

Spread the word