Hillary Clinton Was Politically Incorrect, but She Wasn't Wrong About Trump's Supporters

This week Matt Lauer was subject to withering criticism for his ineffectual interrogation of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. In a litany of complaints, one rose above all—Lauer’s failure to challenge Trump’s mendacious claim that he opposed the Iraq War. That Trump was lying is not a matter of opinion, but demonstrable fact.

>Lauer’s inability to cite the record was a striking journalistic failure—but one related to the larger failures implicit in political reporting today. Political reporting, as it is now practiced, is a not built for a world where outright lying is one candidate’s distinguishing feature. And the problem is not limited to the lies the candidate tells, but encompasses the lies we tell ourselves about why the candidate exists in the first place.

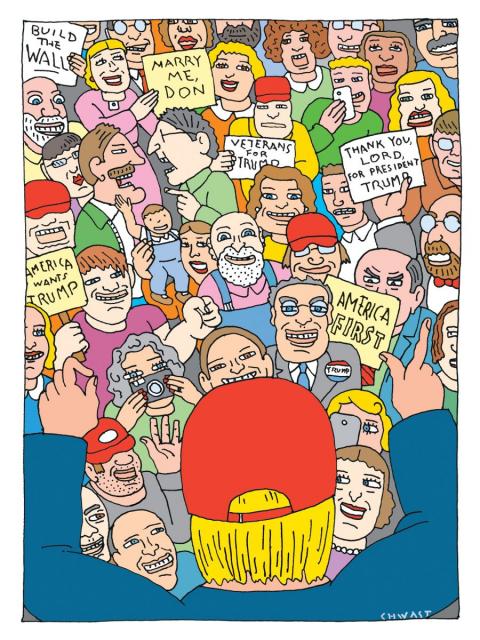

Yesterday, Hillary Clinton claimed that roughly “half of Trump’s supporters” could be characterized as either “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic — you name it.” Clinton hedged by saying she was being “grossly generalistic” but given that no one appreciates being labeled a bigot, that statement still feels harsh––or if you prefer, “politically incorrect.”

Clinton later said that she was “wrong” to say “half,” but reiterated that “it’s deplorable that Donald Trump has built his campaign largely on prejudice and paranoia.”

One way of reporting on Clinton’s statement is to weigh its political cost, ask what it means for her campaign, or attempt to predict how it might affect her performance among certain groups. This path is in line with the current imperatives of political reporting and, at least for the moment, seems to be the direction of coverage. But there is another line of reporting that could be pursued—Was Hillary Clinton being truthful or not?

Much like Trump’s alleged opposition to the Iraq War, this not an impossible claim to investigate. We know, for instance, some nearly 60 percent of Trump’s supporters hold “unfavorable views” of Islam, and 76 percent support a ban on Muslims entering the United States. We know that some 40 percent of Trump’s supporters believe blacks are more violent, more criminal, lazier, and ruder than whites. Two-thirds of Trump’s supporters believe the first black president in this country’s history is not American. These claim are not ancillary to Donald Trump’s candidacy, they are a driving force behind it.

When Hillary Clinton claims that half of Trump’s supporters qualify as “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic,” data is on her side. One could certainly argue that determining the truth of a candidate’s claims is not a political reporter’s role. But this is not a standard that political reporters actually adhere to.

Determining, for instance, whether Hillary Clinton has been truthful about her usage of e-mail while she was secretary of state has certainly been deemed part of the political reporter’s mission. Moreover, Clinton is repeatedly—and sometimes validly—criticized for a lack of candor. But all truths are not equal. And some truths simply break the whole system.

Open and acknowledged racism is, today, both seen as a disqualifying and negligible feature in civic life. By challenging the the latter part of this claim, Clinton inadvertently challenged the former. Thus a reporter or an outlet pointing out the evidenced racism of Trump’s supporters in response to a statement made by his rival risks being seen as having taken a side not just against Trump, not just against racism, but against his supporters too. Would it not be better, then, to simply change the subject to one where “both sides” can be rendered as credible? Real and serious questions about intractable problems are thus translated into one uncontroversial question: “Who will win?”

It does not have to be this way. Indeed, one need not even dispense with horse-race reporting. One could ask, all at once, if Clinton was being truthful, how it will affect her chances, and what that says about the electorate. But that requires more than the current standard for political media. It means valuing more than just a sheen of objectivity but instead reporting facts in all of their disturbing reality.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is a national correspondent at The Atlantic, where he writes about culture, politics, and social issues. He is the author of The Beautiful Struggle and Between the World and Me.

Spread the word