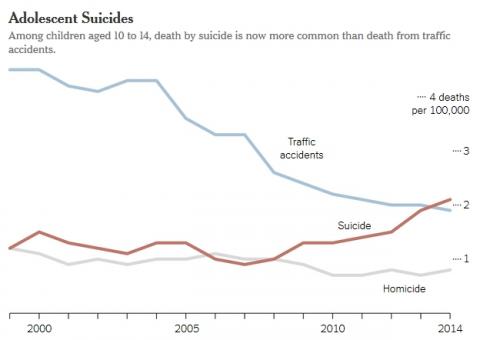

WASHINGTON — It is now just as likely for middle school students to die from suicide as from traffic accidents.

That grim fact was published on Thursday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They found that in 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, the suicide rate for children ages 10 to 14 had caught up to their death rate for traffic accidents.

The number is an extreme data point in an accumulating body of evidence that young adolescents are suffering from a range of health problems associated with the country’s rapidly changing culture. The pervasiveness of social networking means that entire schools can witness someone’s shame, instead of a gaggle of girls on a school bus. And with continual access to such networks, those pressures do not end when a child comes home in the afternoon.

“It’s clear to me that the question of suicidal thoughts and behavior in this age group has certainly come up far more frequently in the last decade than it had in the previous decade,” said Dr. Marsha Levy-Warren, a clinical psychologist in New York who works with adolescents. “Cultural norms have changed tremendously from 20 years ago.”

Death is a rare event for adolescents. But the unprecedented rise in suicide among children at such young ages, however small the number, was troubling and federal researchers decided to track it. In all, 425 children ages 10 to 14 killed themselves in 2014. In contrast, 384 children of that age died in car accidents.

“This graph is really surprising,” said Sally Curtin, an expert at the National Center for Health Statistics who analyzed the data. “We think of traffic accidents as so commonplace.”

The crossing-over point was reached in part because suicide had spiked, but also because fatal traffic accidents had declined.

In 1999, the death rate for children ages 10 to 14 from traffic accidents — about 4.5 deaths per 100,000 — was quadruple the rate for suicide. But by 2014, the death rate from car crashes had been cut in half, part of a broader trend across the entire population. The suicide rate, however, had nearly doubled, with most of the increase happening since 2007. In 2014, the suicide death rate was 2.1 per 100,000.

Far more boys than girls killed themselves in 2014 — 275 boys to 150 girls — in line with adults in the general population. American men kill themselves at far higher rates than women. But the increase for girls was much sharper — a tripling, compared with a rise of about a third for boys.

The reasons for suicide are complex. No single factor causes it. But social media tends to exacerbate the challenges and insecurities girls are already wrestling with at that age, possibly heightening risks, adolescent health experts said. (The data published Thursday did not include methods, but an earlier report gave those details.)

“Social media is girl town,” said Rachel Simmons, the author of “Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls.” “They are all over it in ways that boys are not.”

Statistically, girls dominate visual platforms like Facebook and Instagram where they receive instant validation from their peers, she said. It also is a way to quantify popularity, and take things that used to be private and intangible and make them public and tangible, Ms. Simmons added.

“It used to be that you didn’t know how many friends someone had, or what they were doing after school,” she said. “Social media assigns numbers to those things. For the most vulnerable girls, that can be very destabilizing.”

The public aspect can be particularly painful, Dr. Levy-Warren said. Social media exponentially amplifies humiliation, and an unformed, vulnerable child who is humiliated is at much higher risk of suicide than she would otherwise have been.

“If something gets said that’s hurtful or humiliating, it’s not just the kid who said it who knows, it’s the entire school or class,” she said. “In the past, if you made a misstep, it was a limited number of people who would know about it.”

Another profound change has been that girls are going through puberty at earlier ages. Today girls get their first period at age 12 and a half on average, compared with about 16 at the turn of the 20th century, according to “The New Puberty,” a 2014 book that describes the phenomenon. That means girls are becoming young women at an age when they are less equipped to deal with the issues that raises — sex and gender identity, peer relationships, more independence from family. Girls experience depression at twice the rate of boys in adolescence, Ms. Simmons said, a pattern that continues into adulthood.

What is more, they live in a culture of fast answers and immediate change. That compounds the pressure.

“For a young girl who starts to develop breasts, hips, body hair — it’s a long haul before you land,” Dr. Levy-Warren said. “You don’t really know how you’re going to look for a number of years, and a lot of kids don’t know how to wait anymore. It’s just so painful.”

She added, “There’s this collision of emotional need, social circumstances and a sense of needing an immediate answer.”

Depression is being diagnosed more often these days, and adolescents are taking more medication than ever before, but Dr. Levy-Warren cautioned that it was not clear whether that is because more people are actually depressed, or because it is simply being identified more than before.

Suicide is just the tip of a broader iceberg of emotional trouble, experts warn. One recent study of millions of injuries in American emergency departments found that rates of self-harm, including cutting, had more than tripled among 10- to 14-year-olds. “This is particularly concerning as this type of injury often heralds suicidal behavior,” the researchers wrote.

Jan Hoffman contributed reporting from New York.

What to Do If You Need Help

The National Institute of Mental Health recommends this site. It also warns that reporting on suicide can lead to so-called suicide contagion, in which exposure to the mention of suicide within a person’s family, peer group or in the media can lead to an increase in suicides.

There are many groups that help people having suicidal thoughts. One, Crisis Text Line, inspired by teenagers’ attachment to texting but open to people of all ages, provides free assistance to anyone who texts “help” to 741-741.

If you prefer to talk on the phone, N.I.H. recommends the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Spread the word