When major beer label Budweiser announced they would rename their product “America” through the 2016 U.S. election, it raised droll hackles from a variety of observers. George Will suggested in the conservative National Review that the beer was less than fully American because it was produced by a foreign-owned firm, an irony also observed in the more liberal Washington Post. John Oliver’s HBO staff did what most US media did in 2016, and took the opportunity to give more TV time to the Trump campaign, in this case to mock Trump’s taking credit for the name change. Most commenters counted themselves clever for being aware the Bud label is foreign-owned, but all of them missed the real point: It’s not that “America” is foreign-owned, but that it’s owned by a brand-new global semi-monopoly that perfectly represents the power-mongering of neoliberal capitalism.

Macrobrew

There are indeed American men and women who will tell you it broke their hearts when in 2008 Anheuser-Busch was bought by the InBev transnational. InBev is itself a product of the merged Belgian InterBrew giant and the Brazilian conglomerate AmBev, as Barry Lynn reviews in his book on market concentration, Cornered. Lynn observes that this merger, along with 2007’s union of Miller and Coors under South African Breweries’ control, meant that beer-loving America was subject to corporate decisions made further and further away, and thus “basically reduced to reliance on a world-bestriding beer duopoly, run not out of Milwaukee or St. Louis but out of Leuven, Belgium, and Johannesburg, South Africa.”

And now, just Belgium! Unmentioned in any of the recent rash of commentary was that “America’s” owner AB InBev itself announced this year a $108 billion purchase of SAB Miller, which together would sell about 30% of the world’s beer, including 45% of total beer sales in the United States. The merger would create a “New World of Beer” in which AB InBev will have “operations across multiple continents and a host of countries,” as the business press described it. The Financial Times projected that the combined global giant is expected “to control almost half the industry’s total profits.” SAB Miller will also benefit from bringing its operations under AB InBev’s umbrella, since the latter pays an incredibly low effective tax rate in its Belgian corporate home, paying well under 1% on its nearly $2 billion profit in 2015.

Of course, regulators have to approve large-scale mergers in each of the many, many countries in which the merged empires do business. The European Union’s competition laws, and antitrust law in the United States, are meant to bring legal action against monopolists, or firms planning to merge into something close to one. But in the neoliberal era, a capital fact is the steep drop-off of anti-monopoly suits—the business press has reported that, from Reagan to Obama, the repeated promise to aggressively enforce limits to market concentration “hasn’t worked out that way.” And indeed, for the proposed hopsopoly the news is so far, so good. In addition to Australia and South Africa, the European Union is set to allow the consolidation, China’s Ministry of Commerce okayed the plan and the U.S. Justice Department approved the $100 billion deal, with reservations (see below).

These approvals require certain divestments—sales of pieces of the corporate empires before, or just after, they merge. Such sales can keep market concentration numbers just low enough for regulators to sign off. Yet these deals are so big that the divestments are themselves concentrating the market—Molson Coors is buying AB InBev’s share of their currently joint-owned MillerCoors for $12 billion. These spun-off assets mean Molson Coors will itself have a 25% share of the U.S. beer market, second only to the new SAB-AB InBev combination. In the same way, Constellation Brands became the third-largest American brewer by buying several beer labels from the Mexican firm Grupo Modelo back in 2013, when InBev was buying it and needed to divest a few brands to appease regulators.

Tapping the Craft Keg

Smaller-batch craft beers produced by independent microbrewers provides limited escape from monopolized beer. Constellation paid a full $1 billion for the California craft brewer Ballast Point, in a move the Wall Street Journal suggested “signals that the craft-beer industry, which has a roughly 10% market share in the U.S., has crossed a threshold and become a big business that large brewers expect to continue to grow in the years to come.” The growth potential of microbrews is a valuable opportunity for the majors, especially considering that beer’s share of total U.S. alcoholic-beverage spending fell in 2015 for the sixth straight year, and not just to its perennial foe—wine—but also to liquor as the craft cocktail trend flourishes. And this is in spite of the industry spending over a billion (yes, billion) dollars annually just on TV ads.

This all means that the future growth center of microbrews is increasingly essential to the industry majors, as are export markets. But the growth hopes for microbrews are dimming. The industry must look fearfully at the slowing growth of craft labels, with a mid-single digit growth rate in 2015-16, down from double digits in previous years. What growth there is, is concentrated in the labels held by the industry giants. Market observers notice that while niche labels are still taking market share from the majors, albeit more slowly, “AB InBev’s own U.S. craft portfolio ... increased sales 36% in the first half [of 2016]. After a spate of acquisitions, most notably that of Goose Island, AB InBev is the third-largest craft brewer in the country,” although that reflects the fragmented contours of that market segment. In the less concentrated craft market, few beers have a large market share, unlike in large-scale commercial brewing. The Journal notes, “Craft beer accounts for just 1% of the company’s total volume,” still an important future growth center for what they call “big beer.”

That slowing craft growth is having big effects on the markets for beer ingredients, especially hops, the flowering body of the Humulus lupulus plant used to give beers their bitter or sweet flavors. Hops suppliers haven’t been able to keep up with spiking demand from craft brews for a wide array of obscure varieties, despite a growing proportion of U.S. hops growers producing for small labels since the global brands’ hops are now mostly grown in Germany. The slow-growing plant, and the fast-changing demand for particular varieties have limited the ability of hops growers to keep pace, and with the market’s own growth now slowing, the fear is rising of an oversupply in the industry if crops are only harvested as demand fades. The very small size of the many craft labels, and their uncertain prospects, means farmers are often resistant to committing their production to obscure microbrewers.

Economies of Ale

Scale economies occur when a firm’s per-unit costs decrease as the scale of production increases. Typically observed in industries, like manufacturing, that have high up-front costs, economies of scale arise from “spreading” a large starting investment over a growing amount of output. A brewery that cost $10 million to build, and which produces one million cans or bottles in a year, would have a per-unit fixed cost of $10. Producing ten million cans, the per-unit fixed cost is just a dollar per can. The big costs of brewing tanks, sturdy equipment for mixing the ground grains and the flavorful hops, the cost of the actual brewery structure itself—all add to a brewery’s starting investment and create the potential for scale economies.

Economies of scale are usually observed at the plant or factory level, but can also arise at higher levels of operation, including in administration. For example, two large companies may merge and then lay off one of their human resources departments, if one computerized HR office can handle all the employees at the new, merged firm. But these returns to scale, associated with a higher level of market concentration, are often counterbalanced by increasing layers of corporate bureaucracy and the challenges of managing large commercial empires.

So returns to scale constitute strong incentives for firms to grow, both in dollar terms and in market share, gaining scale and profitability. They do have limits, but once firms have reached large and cost-efficient sizes they are often happy to go on growing or merging, in order to gain more market power. The result is that in many industries, from the manufacturing sector to telecommunications to financial services, rich competitive markets give way over time to other market structures, including the few large companies of an oligopoly or the single colossal monopolist.

Growth-seeking is also driving the major brewers toward foreign markets, as the New York Times’ DealBook feature observes that “in China, Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller are betting on premium products,” with “the two beer behemoths” buying up large stakes in China’s top- selling brands. “Together, the international brewers account for about one-third of the overall beer market in China. As they pursue a merger, given their dominance, Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller are expected to prune their portfolio in China to keep regulators happy,” and indeed the popular Snow brand was ultimately sold off to a Chinese state-owned company. These different growth prospects are all threatened by a gradual worldwide reconsideration of health benefits of modest alcohol consumption. While public health agencies had for years considered small amounts of alcohol to have some health upsides (mostly heart-related), the emerging view is that these benefits are outweighed by health risks, leading to a growing number of health agencies amending their guidance to recommend lower levels of consumption.

As with other industries, from tobacco to chemicals, the industry is pushing back in significant part by getting directly involved in the research process. A former cigarette-industry executive now working for booze giant Diageo claimed in the press that a study critical of alcohol advertising was “junk science” and said, “We push back when there are dumb studies.” This raises again the prospect of “science capture,” the growing phenomenon of private entities with a material interest attempting to influence the scientific process. Indeed, some are funding their own research, the findings of which unsurprisingly support the economic activity of the industry doing the funding.

High-Proof Political Economy

The corporate beer empires aren’t shy about using their newly enlarged market power, either. Cornered author Barry Lynn recounts a classic episode in which Anheuser-Busch targeted Boston Beer, the owner of Sam Adams:

For reasons still not entirely clear, the giant firm unleashed a devastating, multifront assault by armies of lawyers, lobbyists, and marketers who accused Boston Beer (to the government and to the public through the media) of deceptive packaging. Anheuser-Busch then followed up with an even more devastating second assault, in which it locked Boston Beer products out of the immensely powerful distribution networks that it controls. Ultimately, an arbitrator rejected all of the megafirm’s contentions, and Boston Beer survived to brew another day, but the company, less than 1% the size of Anheuser-Busch, was left on the verge of bankruptcy.

Boston Beer remains the second-largest U.S. craft brewer, but the industry has not forgotten this power play.

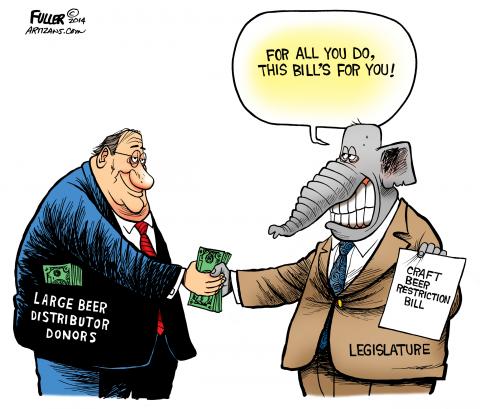

And today’s even-bigger corporations are brewing up new retail-level strategies. The Journal reports that AB InBev had planned to “offer some independent distributors in the U.S. annual reimbursements of as much as $1.5 million if 98% of the beers they sell are AB InBev brands.” The money would come in the form of the conglomerate footing the bill for distributors’ share of marketing costs, like displays at the retail level. The move has craft brewers crying foul, and understandably, since it leaves independents with a pitifully small fraction of store display space and promotion dollars left for them to fight over. The incentive plan also requires that distributors only carry craft brewers that operate below certain low thresholds of annual production, which most do.

The importance of this corporate proposal lies in the middle-man layer of the industry, created by state laws at the end of Prohibition. Beer brewers must sell their output to distributors, who then sell it on to the retailers where you pick up a six-pack. While there are hundreds of distributors in the United States, most are under agreement to sell exclusively either product from AB InBev or MillerCoors. But in addition to deals like these, the beer manufacturers are also able to buy and operate their own distributors—the state of California is investigating AB InBev after it bought two distributors in the state, with concerns about the giant declining to carry independent micros. The company presently owns 21 distributors in the United States and has further used its gigantic revenues to continue buying up independent brewers like Goose Island—now part of the global company and thus available to AB InBev’s distributors—on its terms.

Raise a Glass

Opiate of the Masses

Fittingly, the first great scholar of capital concentration, Karl Marx, was a product of the beer-loving German people. Marx pioneered the study of capitalism’s near-universal gravitational tendency, and for today’s economy we have an analytical vocabulary to help understand the growth of capital.

- Concentration of capital, the growth of market share by a few big firms within a market.

- Consolidation, the growth of corporate capital by buying firms in separate industries.

- Capital accumulation, the overall growth in the capital stock of an economy.

Marx wrote in his giant classic study, Capital, that “The laws of this centralization of capitals, or of the attraction of capital by capital,” depended ultimately on “the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions.” In other words, fancier technology and more expensive investments make it harder for small brewers to operate at the low costs of established firms.

Many more conservative economists have resisted this conclusion, and insisted that free markets have an enduringly competitive character, even in older industries. Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian economist and one of the conservative world’s most revered thinkers, derided the argument that “technological changes have made competition impossible in a constantly increasing number of fields. ... This belief derives mainly from the Marxist doctrine of the ‘concentration of industry.’”

Marx might reply by raising a glass in toast, filled with amber-hued global corporate beer.

Popular opposition to the megamerger has been scattered, in a year punctuated by billion-dollar mergers in agriculture, chemicals, insurance, and drugs. In South Africa, a market important enough to require merger clearance as a condition of the deal (and the “SA” in “SABMiller”), a labor union objected to the deal’s terms. Among those terms are rules covering a 2010 issue of SAB shares to workers and retailers, which would have matured in 2020. The union membership prefers to “cash out” earlier, or be granted an up-front payment in addition to the existing shares. Labor opposition to market concentration is always notable, although this case revolves more around the treatment of the workforce on a quite specific compensation issue, rather than an objection to capital accumulation in general. The ultimate approval of the merger by the South Africa’s Competition Tribunal was significantly a foregone conclusion. As Bloomberg observes, South Africa’s bond rating has been downgraded, reflecting world investor fear of policy changes not to their advantage. This meant that the country’s leader, President Jacob Zuma of the African National Congress (ANC), was especially eager to approve the megadeal, all the more after recent poor showings for the ANC in local races. This led to unusually prompt action by Zuma—Bloomberg noted in March 2016 that “SABMiller itself is still waiting for approval to merge its African soft-drink bottling assets, 15 months after it filed the request,” while the AB InBev-SAB merger took just half that time.

A number of other unions represent organized brewery workers in the United States, including the Machinists, the Operating Engineers, the Auto Workers, and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT). The IBT lodged an objection to a particular feature of the deal, writing a letter to the Attorney General requesting antitrust scrutiny of the related closure of the “megabrewery” operated by MillerCoors in Eden, N.C. While MillerCoors is to be sold to Molson as part of the deal, the closure does affect the market significantly, particularly since the huge facility produces 4% of all U.S. beer output, making the reduction more than can be compensated for at other facilities. This significant tightening of supply raised the question of antitrust violation to the IBT, due both to the further concentration of the market but also to the fact that the facility was essential for rival brewer Pabst, which for years has not brewed its own hipster swill but has had it produced by Miller under contract at the Eden brewery. Miller had previously indicated it has no interest in maintaining the deal past its expiration. The U.S. legal settlement appears to make no mention of this issue, but Pabst is now suing Miller over the terms of their brewing agreement, and the IBT lawsuit against Miller continues. For their part, unions from the acquiring company have also been skeptical, noting that the giant corporation has cut its Belgian workforce in half, to just 2,700 over ten years. The Times reports, “They also predict that the company will load up on debt to buy SABMiller, leading to pressure for further cutbacks.” Beyond labor, the large and still-growing craft sector of the marketplace has looked with suspicion on industry consolidation for some time and had a clear eye of the stakes, if not typically engaging in action beyond contacting legislators or regulators. The press in brewery-heavy St. Louis describes how craft independents view the deal “warily,” as “smaller breweries remain worried a larger A-B InBev will have more influence on what beers retailers stock on their shelves and hamper access to supplies such as hops.” They also see influence-building intent behind legislation the corporations have supported, like a bill passed by the Missouri state legislature allowing brewers to lease large commercial coolers to retailers. Craft brewers oppose the governor signing the bill, “arguing only large brewers such as A-B InBev can afford to buy the coolers, which will likely be filled by retailers with A-B brands.”

Likewise, industry rag All About Beer Magazine has expressed enormous skepticism of not just the new megadeal but the whole history of consolidation in the industry, in the United States and the UK. In a beautiful expression of widespread market- skepticism, Lisa Brown wrote, “This is about a company that has historically used the strategy of controlling and purchasing the wholesale tier of the industry now getting much more influence and potential control of that sector, while also gaining a lot more spending money for lawyers and lobbying.” Reflecting these popular sentiments, the Brewers Association—the industry group representing the many small craft brewers and independent labels—requested significant safeguards from the Department of Justice should the deal clear. It wanted an end to AB InBev’s preferential distribution and limits to its “self-distribution” plans, since influence over distributors gives big brewers an additional potential lever of power over retailers. Evidently the DoJ heard the complaints, because (happily for today’s craft drinkers) the department’s allowance of the merger came with numerous conditions on top of the planned divestments, with some directed at these kinds of maneuvers. The department limited AB InBev from enforcing distributor incentive deals (like the one above), and crucially imposed a cap of 10% on the proportion of AB InBev’s sales that can be sold through wholly-owned distributors. This is intended to limit the giant’s influence over distribution and hopefully reserve shelf space for independent labels.

The agency further put the Big Beer giant under a new requirement to submit for approval all acquisitions of craft beers for the next ten years, benefiting consumers desiring a wider range of brews, and preserving more successful independents from corporate concentration. These requirements, resulting from demands for redress from retailers and craft brewers, do sound satisfyingly stringent. However, the firm retains enormous market power, is strategically positioned to grow in developing markets (especially in Africa), and can be expected to work to undermine or evade these rules in the future. As always, antitrust rules keep oligopoly from maturing into full monopoly, and impose meaningful limits on anticompetitive practices, at least when enforced aggressively. That enforcement tends to ebb and flow however, and it’s unclear how the Trump administration will prioritize breaking up giant mergers with its emerging neoliberal shape.

With the worldwide trend for tighter corporate ownership and global oligopoly, it’s the investor class that’s getting fat off our beer. A more aggressive labor movement of organized malters and brewers, reinforced by irate craft consumers, could resist further job cuts and demand bolder regulatory roadblocks to this consolidation. Or better yet, rather than choosing your poison between super-concentrated markets or moderately concentrated ones, an incensed and tipsy anticapitalist movement could take over these global giants’ facilities and brew the beers themselves.

There are few consumers who enjoy shop-talk about their personal favorites more than beer drinkers, providing a natural opportunity for sharing this and other episodes of capitalist globalization. Raising consciousness about capitalism’s predations, even in beer, could encourage a movement to socialize brewing. In a democratically managed economic system, the freewheeling ethos of the microbrew movement would be free to flourish without being blackballed out of the market by the majors, or bought out if they manage to succeed.

Now that would be a happy hour!

Spread the word