By Sally Bedell Smith

Penguin/Random House, 624 pages

Hardcover: $32.00 (E-book also available)

April 4, 2017

ISBN-10: 1400067901

ISBN-13: 978-1400067909

For at least a decade, senior aides at Buckingham Palace have been quietly finessing arrangements for the moment when the Queen dies and her son Prince Charles becomes sovereign. One of their chief concerns, apparently, is that republicans may try to use the interval between the death of the old monarch and the coronation of the new one to whip up anti-royal sentiment. In order to minimize the potential for such rabble-rousing, they propose to speed things up as much as decorum will allow: in contrast to the stately sixteen-month pause that elapsed between the death of King George VI, in February, 1952, and the anointing of the Queen, in June, 1953, King Charles III will be whisked to Westminster Abbey no later than three months after his mother’s demise.

The threat of a Jacobin-style insurgency in modern Britain would seem, on the face of it, rather remote. Despite successive royal scandals and crises, support for the monarchy has remained robust. In the wake of Princess Diana’s death in 1997, when the reputation of the Windsors was said to have reached its nadir, the Scottish writer Tom Nairn sensed that the crowds of mourners lining the Mall had “gathered to witness auguries of a coming time” when Britain would at last be freed from “the mouldering waxworks” ensconced in Buckingham Palace. But, almost twenty years later, roughly three-quarters of Britons believe that the country would be “worse off without” the Royal Family, and Queen Elizabeth II, who recently beat out Queen Victoria to become the longest-reigning monarch in British history, continues to command something approaching feudal deference. Last year, to honor her ninetieth birthday, legions of British townspeople and villagers turned out to paint walls and pick up litter, in a national effort known as “Clean for the Queen.”

There is some reason to doubt, however, whether such loyalty will persist once the Queen’s son, now sixty-eight years old, ascends the throne. His Royal Highness Prince Charles Philip Arthur George, Prince of Wales, K.G., K.T., G.C.B., O.M., A.K., Q.S.O., P.C., A.D.C., Earl of Chester, Duke of Cornwall, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles, and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland, is a deeply unpopular man. Writers in both the conservative and the liberal press regularly refer to him as “a prat,” “a twit,” and “an idiot,” with no apparent fear of giving offense to their readership. In a 2016 poll, only a quarter of respondents said that they would like Charles to succeed the Queen, while more than half said they would prefer to see his son Prince William crowned instead. Even among those who profess to think him a decent chap, there is a widespread conviction that he does the monarchy more harm than good. “Our Prince of Wales is a fundamentally decent and serious man,” one conservative columnist recently wrote. “He possesses a strong sense of duty. Might not it be best expressed by renouncing the throne in advance?”

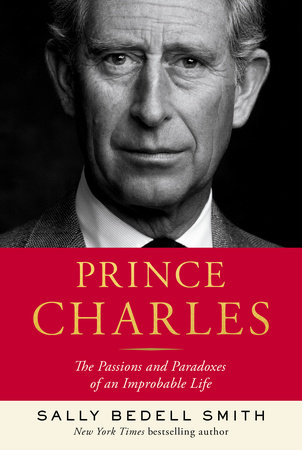

How this enthusiastic and diligent person, who has frequently stated his desire to be a good, responsible monarch, managed to incur such opprobrium is the central question that the American writer Sally Bedell Smith sets out to answer in a new biography, “Prince Charles: The Passions and Paradoxes of an Improbable Life” (Random House). Hers is not an entirely disinterested investigation. As might be inferred from her two previous alliteratively subtitled works—“Diana in Search of Herself: Portrait of a Troubled Princess” and “Elizabeth the Queen: The Life of a Modern Monarch”—Smith is an avid monarchist. For anyone invested in the survival of the royals, Prince Charles presents a challenge, and Smith’s stance is very close to what one imagines a senior palace aide’s might be: Charles is far from ideal, but he is what we’ve got, and there can be no talk of mucking about with the law of succession and replacing him with his son. Once you start allowing the popular will to determine who wears the crown, people are liable to wonder why anyone is wearing a crown in the first place.

Smith’s mission is, therefore, to reconcile us to the inevitability of King Charles III and to convince us that his reign may not be as insufferable as is generally feared. Having had the honor of meeting the Prince “socially” on more than one occasion, she can attest that he is “far warmer” than the tabloids would have you think. She can also vouch for his “emotional intelligence,” “capacious mind,” “elephantine memory,” “preternatural aesthetic sense,” “talent as a consummate diplomat,” and “independent spirit.”

Early on, however, it becomes apparent that Smith’s public-relations instincts are at war with a fundamental dislike of her subject. The grade-inflating summaries she offers at the beginning and the end of the book are overpowered by the damning portrait that emerges in between. The man we encounter here is a ninny, a whinger, a tantrum-throwing dilettante, “hopelessly thin-skinned . . . naïve and resentful.” He is a preening snob, “keenly sensitive to violations of protocol,” intolerant of “opinions contrary to his own,” and horribly misled about the extent of his own talents. (An amateur watercolorist, he once offered Lucian Freud one of his paintings in exchange for one of Freud’s; the artist unaccountably demurred.) He is a “prolix, circular” thinker, “more of an intellectual striver than a genuine intellectual,” who extolls Indian slums for their sustainable way of life and preaches against the corrupting allure of “sophistication” while himself living in unfathomable luxe. (He reportedly travels with a white leather toilet seat, and Smith details his outrage on the rare occasions when he has to fly first class rather than in a private jet.) Although the book would like to be a nuanced adjudication of the Prince’s “paradoxes,” it ends up becoming a chronicle of peevishness and petulance.

Prince Charles was three years old when he became heir apparent. Asked years later when it was that he had first realized he would one day be king, he said that there had been no particular moment of revelation, just a slow, “ghastly, inexorable” dawning. Doubts about his fitness for his future role were raised from the start. As a timorous, sickly child, prone to sinus infections and tears, he was a source of puzzlement and some disappointment to his parents. His mother, whom he would later describe as “not indifferent so much as detached,” worried that he was a “slow developer.” His father, Prince Philip, thought him weedy, effete, and spoiled. Too physically uncoördinated to be any good at team sports, too scared of horses to enjoy riding lessons, and too sensitive not to despair when, at the age of eight, he was sent away to boarding school, he was happiest spending time with his grandmother the Queen Mother, who gave him hugs, took him to the ballet, and, as he later put it, “taught me how to look at things.” Neither physical demonstrativeness nor sensitivity to art was considered a desirable trait by the rest of his family. Charles told an earlier biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby, about a time when he ventured to express enthusiasm about the Leonardo da Vinci drawings in the Royal Library at Windsor; his parents and siblings gazed at him with an embarrassed bemusement that, he said, made him feel “squashed and guilty,” as if he had “in some indefinable way let his family down.” (Charles has continued to define himself against his family’s philistinism, boasting in his letters and journals of his intense, lachrymose responses to art, literature, and nature.)

In an effort to build the character of his soppy, aesthete son, Prince Philip sent him to his own alma mater, Gordonstoun, a famously spartan boarding school in Scotland founded on the promise of emancipating “the sons of the powerful” from “the prison of privilege.” Charles—the jug-eared, non-sportif future king—was a prime target for bullying, and when he wasn’t being beaten up he was more or less ostracized. (Boys made “slurping” noises at anyone who tried to be nice to him.) That he survived this misery was largely due to the various dispensations he was afforded as a V.I.P. pupil. He was allowed to spend weekends at the nearby home of family friends (where he could “cry his eyes out” away from the jeers of other boys) and, in his final year, was made head boy and given his own room in the apartment of his art master. He had taken up the cello by this point, and, although he was, by his own admission, “hopeless,” the art master arranged for him to give recitals at the weekend house parties of local Scottish aristocrats.

Throughout Charles’s youth, he was pushed through demanding institutions for which he was neither temperamentally nor intellectually suited, and where rules and standards had to be discreetly adjusted to accommodate him. When he went to Cambridge University, the master of Trinity College, Rab Butler, insisted that he would receive no “special treatment.” But the fact that he had been admitted to Trinity at all, with his decidedly below-average academic record, suggested otherwise, as did the colloquium of academics convened to structure a bespoke curriculum for him, and the unusually choice suite of rooms (specially decorated by the Queen’s tapissier) that he was granted as a first-year student. When he received an undistinguished grade in his final exams, Butler said that he would have done much better if he hadn’t had to carry out royal duties.

In the Royal Navy, which Charles entered at his father’s prompting, his superiors, faced with his “inability to add or generally to cope well with figures,” sought to “build in more flexibility and to tailor duties closer to his abilities.” They changed his job from navigator to communications officer, and his performance reports laid diplomatic emphasis on his “cheerful” nature and “charm.”

Even Charles’s love life was choreographed for him with the sort of elaborate care and tact usually reserved for pandas in captivity. Throughout his twenties, his public image was that of a dashing playboy. But this reputation appears to have been largely concocted by the press and his own aides, in an effort to make an awkward, emotionally immature young man more appealing and “accessible” to the British public. Charles’s great-uncle Lord Mountbatten blithely informed Time that the Prince was forever “popping in and out of bed with girls,” but to the extent that this was the case it was thanks mostly to the assiduous efforts of his mentors. Having told Charles that a man should “have as many affairs as he can,” Mountbatten offered up his stately home as a love shack.

Mountbatten also set to work finding a suitable woman for Charles to marry. At the time, virginity was still a non-negotiable requirement for the heir apparent’s bride. (“I think it is disturbing for women to have experiences if they have to remain on a pedestal after marriage,” Mountbatten wrote to Charles.) Thus, Camilla Shand, the “earthy” woman with whom Charles fell in love at the age of twenty-three, was regarded as an excellent “learning experience” for the Prince but decidedly not wife material. Charles seems to have accepted this judgment and the stricture on which it was based, more or less unquestioningly. Almost a decade later, his misgivings about marrying Lady Diana Spencer, a woman twelve years his junior, whom he did not love, or even know very well, caused him to weep with anguish on the eve of their wedding, but he went through with it anyway, believing that, as he wrote in a letter, it was “the right thing for this Country and for my family.”

When that marriage exploded, Diana’s superior instincts for wooing and handling the press insured that Charles emerged as the villain of the piece. But it seems safe to say that the union visited equal misery on both parties. One of the chief marital shocks for Charles was Diana’s lack of deference. He had assumed that the slightly vapid teenager he was settling for would at least be docile, but she turned out to be the biggest bully he had encountered since Gordonstoun. She taunted his pomposity, calling him “the Great White Hope” and “the Boy Wonder.” She told him that he would never become king and that he looked ridiculous in his medals. When he tried to end heated arguments by kneeling down to say his prayers before bed, she would keep shrieking and hit him over the head while he prayed.

Charles had always disliked the playboy image that had been thrust upon him, feeling that it did a disservice to his thoughtfulness and spirituality, and part of what he hoped to acquire by getting married was gravitas: “The media will simply not take me seriously until I do get married and apparently become responsible.” The strange artificiality of his youthful “achievements,” and the nagging self-doubt it engendered, seems to have left him peculiarly vulnerable to the blandishments of advisers willing to reassure him that he was actually a brilliant and insightful person, who owed it to the world to share his ideas.

The canniest of these flatterers, and the one who had the most lasting impact, was Laurens van der Post, a South African-born author, documentary filmmaker, and amateur ethnographer. He dazzled Charles with his visionary talk—of rescuing humanity from “the superstition of the intellect” and of restoring the ancients’ spiritual oneness with the natural world—and then convinced Charles that he was the man to lead the crusade. “The battle for our renewal can be most naturally led by what is still one of the few great living symbols accessible to us—the symbol of the crown,” he wrote to the Prince. It’s no wonder that Charles was seduced. The life of duty opening up before him was a dreary one of cutting ribbons at the ceremonial openings of municipal swimming pools and feigning delight at the performances of foreign folk dancers. Here was an infinitely more alluring model of princely purpose and prerogative.

Under the influence of van der Post and his circle, Charles began exploring vegetarianism, sacred geometry, horticulture, educational philosophy, architecture, Sufism. He received Jungian analysis of his dreams from van der Post’s wife, Ingaret. He visited faith healers who helped him uncork “a lot of bottled feelings.” Staying with farmers in Devon and crofters in the Hebrides, he played at being a horny-handed son of toil. He travelled to the Kalahari Desert and saw a “vision of earthly eternity” in a herd of zebras. On his return from each of these spiritual and intellectual adventures, he sought to share the fruits of his inquiries with his people.

Over the years, Charles has set up some twenty charities reflecting the range of his Bouvard-and-Pécuchet-like investigations. He has written several books, including “Harmony,” a treatise arguing that “the Westernized world has become far too firmly framed by a mechanistic approach to science.” He has sent thousands of letters to government ministers—known as the “black spider memos,” for the urgent scrawl of his handwriting—on matters ranging from school meals and alternative medicine to the brand of helicopters used by British soldiers in Iraq and the plight of the Patagonian toothfish. He has given countless speeches: to British businessmen, on their poor business practices; to educators, on the folly of omitting Shakespeare from the national curriculum; to architects, on the horridness of tall modern buildings; and so on.

The stances he takes do not follow predictable political lines but seem perfectly calibrated to annoy everyone. Conservatives tend to be upset by his enthusiasm for Islam and his environmentalism; liberals object to his vehement defense of foxhunting and his protectiveness of Britain’s ancient social hierarchies. What unites his disparate positions is a general hostility to secularism, science, and the industrialized world.

“I have come to realize,” he told an audience in 2002, “that my entire life has been so far motivated by a desire to heal—to heal the dismembered landscape and the poisoned soul; the cruelly shattered townscape, where harmony has been replaced by cacophony; to heal the divisions between intuitive and rational thought, between mind and body, and soul, so that the temple of our humanity can once again be lit by a sacred flame.”

The British tend to have a limited tolerance for sacred flames. They are also ill-disposed to do-gooders poking about in their poisoned souls. (“The most hateful of all names in an English ear is Nosey Parker,” George Orwell once observed.) What’s more, Charles’s sententious interpretation of noblesse oblige leaves him open to the charge of overstepping the constitutional boundaries of his position. A constitutional monarchy requires that the sovereign—and, by extension, the prospective sovereign—be above politics. Their symbolic power and their ability to work with elected governments in a disinterested manner depend on their maintaining an impeccable neutrality on all matters of public policy. The Queen’s enduring inscrutability is often cited as one of the great achievements of her reign, and she has fulfilled her duties to everyone’s satisfaction, with no mystical knowledge beyond dog breeding and horse handicapping. Charles’s refusal to shut up about his views and his brazen efforts to influence popular and ministerial opinion have provoked much ridicule, as well as more serious rebukes. Both Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair had occasion to complain—to him and to the palace—about his interference in the legislative process. “I run this country, not you, sir,” Thatcher is alleged to have told him. But Charles has shown no signs of repentance. Indeed, he has repeatedly indicated that he intends to continue his “activism” after he ascends the throne. “You call it meddling,” he told an interviewer nine years ago. “I would call it mobilizing, actually.”

Historically, the question of how the Prince of Wales should occupy himself while waiting for his parent to die has rarely found a satisfactory answer. Many heirs to the throne have incurred opprobrium on the ground of moral turpitude. A hundred and fifty years ago, in “The English Constitution,” Walter Bagehot noted the temptation for bored princes to become fops and fornicators, and concluded that “the only fit material for a constitutional king is a prince who begins early to reign.”

But Charles, who has been waiting to become king longer than any previous Prince of Wales, does not boast a distinguished record of degeneracy. His greatest known sin is to have resumed his relationship with Camilla while still married to Diana. It’s true that some of the revelations regarding this infidelity were not strictly consonant with the dignity of a future king. In an alleged transcript of a phone conversation between the adulterous couple, the public learned that the Prince yearned to be his ladylove’s tampon. But while it is certainly a dark day for England when the Italian press is emboldened to speak of the heir apparent as “Il Tampaccino,” few have gone so far as to suggest that Charles is too debauched to become king.

Oddly, and perhaps rather tragically, the severest damage to his reputation has come not from his modest history of vice but from his strenuous aspirations to virtue. “All I want to do is to help other people,” he has written. The fact that so many are ungrateful does not deter him: he accepts that, like any of the great men in history who have dared to go against the grain, he must endure derision. “It is probably inevitable that if you challenge the bastions of conventional thinking you will find yourself accused of naivety,” he observed in the introduction to “Harmony.” He is honor-bound to ignore the scorn, and to march on. In 2015, when the Guardian won a ten-year battle to release two batches of the meddlesome “black spider memos,” under Britain’s Freedom of Information Act, he was unabashed. A spokesman defended the Prince’s right “to communicate his experiences or, indeed, his concerns or suggestions to ministers” in any government, and, by then, the law had been obligingly changed to make much royal correspondence exempt from future release. Not long after, there appeared a two-volume, 1,012-page compendium of Charles’s articles and speeches from 1968 to 2012. The books, which retailed at more than four hundred dollars a set, were illustrated with his own watercolors and bound in forest-green buckram on which his heraldic badge—three feathers, a crown, and the motto “Ich dien,” meaning “I serve”—was emblazoned in gold.

Author Sally Bedell Smith is the author of bestselling biographies of Queen Elizabeth II; William S. Paley; Pamela Harriman; Diana, Princess of Wales; John and Jacqueline Kennedy; and Bill and Hillary Clinton. A contributing editor at Vanity Fair since 1996, she previously worked at Time and The New York Times, where she was a cultural news reporter.

[Reviewer Zoë Heller is a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books. She has published three novels, including “Notes on a Scandal.” ]

Spread the word