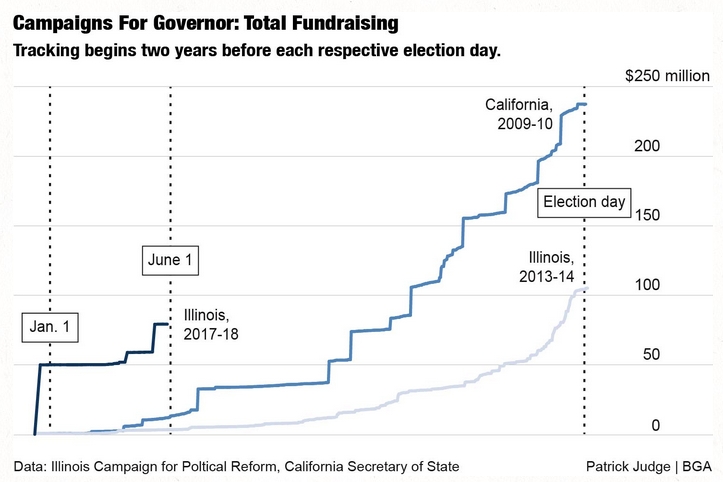

As Illinois approaches a record third year without a budget, the state is well down the road toward another controversial landmark—topping California’s 2010 distinction of holding the most expensive governor’s race in U.S. history.

That contest between eventual winner Jerry Brown, a Democrat, and Republican Meg Whitman cost $252 million. But the 2018 Illinois race to keep or unseat incumbent Bruce Rauner is already one-third of the way there, and well ahead of the fundraising pace of the Brown-Whitman faceoff, with the general election still 17 months away.

Rauner, a wealthy investor who reported income of more than $188 million his first year as governor, has already chipped in $50 million of that into his re-election coffers. His friend Ken Griffin, a billionaire hedge fund founder, gave another $20 million to Rauner.

Among a broad field of declared Democratic contenders, billionaire J.B. Pritzker has so far committed more than $7 million of his own money while making clear there’s a lot more where that came from.

“What’s happening in Illinois is really extreme, but that doesn’t mean it’s an aberration across the country,” said Kent Redfield, a University of Illinois Springfield professor of political science who specializes in campaign finance issues. “We’re getting awfully close to a plutocracy.”

The amounts spent on state political races across the country are soaring as states increasingly become costly battlegrounds for business and labor regulations, taxes, gun and abortion policies and Medicaid spending. The stakes will get even higher as the 2020 Census approaches, with the results then used to draw new districts for legislative and U.S. House seats.

In the four election cycles from 2010 through 2016, races for governor, lieutenant governor, supreme court and legislatures across the nation cost a combined $8.9 billion, according to the Montana-based National Institute on Money in State Politics.

It was more than a century ago that Marc Hanna, the Ohio industrialist and famous Republican political fixer, said, “There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money, and I can’t remember what the second one is.” That remains true today.

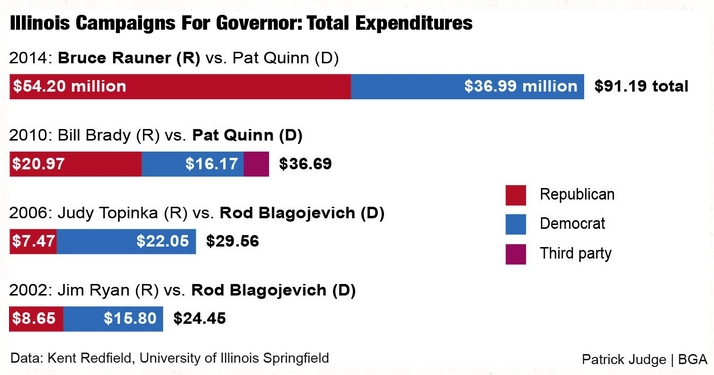

The spending growth has been particularly stunning in Illinois. The 2006 race for Illinois governor cost $29.6 million, the 2010 race cost $37 million and the 2014 race $91 million. Rauner’s campaign alone accounted for $54 million of that 2014 total.

Down the ballot, a $1 million legislative race in Illinois used to be an oddity. There were seven for House and Senate seats in the 2008 Illinois election, costing between $1 million and $2 million. Last year 23 topped $1 million, with five between $5 million and $6 million, according to Redfield’s analysis of state campaign finance records.

Isolating just on House races, there were a dozen in 2014 where spending topped $1 million each, and the combined cost of those races was more than $18 million. By last year, the number of million dollar plus races had grown to 16 and the overall cost to more than $52 million.

“Just think of all that money and the dollars that haven’t gone to higher education, social services and other programs hurt by the budget gridlock,” said Sarah Brune, executive director of the Illinois Campaign for Political Reform. “This kind of spending never loses its shock value.”

It’s certainly not going out of style. Griffin, the founder and CEO of Citadel LLC, is the Republican governor’s largest outside contributor, donating almost $27 million since Rauner first became a candidate in 2013. In a speech to the Economic Club of Chicago that year, Griffin issued a call to arms to business leaders saying, “We need to pick up the phone. We need to pick up the pen.”

People from both parties heard him. Richard Uihlein of packaging giant Uline Corp., real estate mogul Sam Zell, Michael Sacks of Grosvener Capital, a giant asset manager, and Fred Eychaner of media publisher Newsweb Corp. helped swell campaign coffers for governor and statewide offices, as well as the Chicago mayor’s race, by $128 million between 2013 and 2016 election cycle, according to Redfield’s analysis.

Nearly half of that, $61 million, came from Rauner and his wife, Diana. If Pritzker, a venture capitalist and heir to the Hyatt Hotel fortune, wins the Democratic nomination, a general election battle with Rauner is likely to consumed less by issues than the enormous amounts of personal money both can throw into their races.

“More and more outside money, and more and more wealthy people either running themselves or contributing,” said David Yepsen, the former director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

The prospect of Illinois seriously challenging the California spending record is even more remarkable because the Golden State has three times the population of Illinois. What’s more, Illinois is home to just one of the nation’s top 20 media markets, where campaign ads get pricier to run, while California has three of those most expensive markets.

California’s 2010 governor’s race provides a cautionary tale on the limits of big money. Brown, then a former governor mounting a comeback, was outspent 4-to-1 by Whitman, the founder and former CEO of eBay. She spent $177 million – all but $33 million from her own pocket – and still lost by 1 million votes.

It’s also interesting to note that by June 1, 2009—a comparable point in that election cycle to where Illinois is now—all candidates for California governor combined had raised slightly over $11 million, with Whitman accounting for most of that, according to California election records. The amount already raised for the 2018 Illinois governor’s race exceeds that sevenfold.

Whitman’s expensive flop hardly deterred big political spending. Two years later, in a recall campaign against Wisconsin Republican Governor Scott Walker, both sides blew through a combined $80 million in campaign contributions in a state with less than one-sixth the population of California. In 2014, the regularly scheduled governor’s race cost another $80 million.

“I think some of this can be traced to Ronald Reagan and his returning more power and decision-making to the states,” said Mike McCabe, the former executive director of the election watchdog group Wisconsin Democracy Campaign.

Increased campaign spending accelerated in the 2000s, creating “an arms race,” McCabe said, with more expensive governor and legislative races. It spread to state supreme court races because the legality of some of the important legislation that came out of statehouses would ultimately be determined by the states’ highest courts.

“Now it’s working its way down to local city council and school board races,” said McCabe, author of the 2014 book “Blue Jeans in High Places: The Coming Makeover of American Politics.” “I call it the Washington-ization of state politics.”

As political gridlock tightens its hold on Washington, many of the policy battles occur in the states – public employee collective bargaining curbs in Wisconsin; taxes, gun regulations and right-to-work in Missouri; abortion restrictions and bans on sanctuary cities in Texas.

Some states with Republican legislatures are moving to pre-empt the authority of Democratic-controlled cities to raise the minimum wage or, in the case of North Carolina, enshrine LGBT rights. The power of states is likely to grown even more if President Donald Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress move to give states more control over Medicaid.

The current political gridlock in Illinois is in many ways a reflection of the state’s status a political outlier in the rust belt. In recent years, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri and Michigan have elected Republican governors and legislatures who set to work enacting labor restrictions, tax cuts and regulatory changes endorsed by business lobbies.

Illinois, however, remains a largely Democratic fortress – with the exception of Rauner in the governor’s office – and the tension created by that dynamic helps explain the flood of campaign cash.

“I think there’s a belief that there’s more bang for the buck in the states, especially with so much gridlock at the national level,” Redfield said. “That’s why you’re seeing this, and no one is willing to unilaterally disarm.”

This story was written and reported for the Better Government Association by Tim Jones.

Spread the word