Will Republican senators vote yes on a bill this unpopular? To hang on to their jobs, senators have to keep only voters in their own states happy, not the whole nation. Perhaps red-state senators, or even some senators in swing states, might think their states are friendlier to the bill than the nation as a whole.

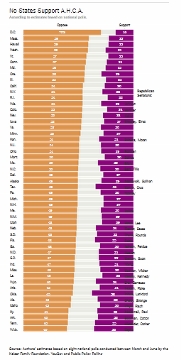

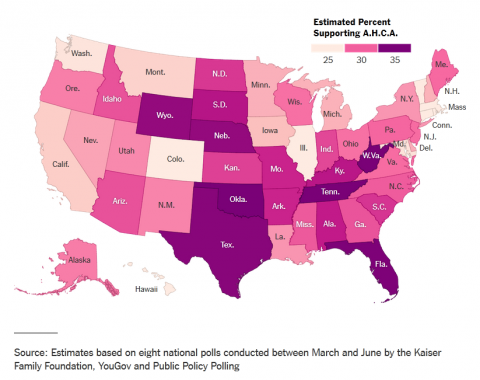

Our research indicates that is not the case. To get a sense of support by state, we combined recent polls to estimate support for the A.H.C.A. in every senator’s home state. Our estimates indicate that not one state favors it.

Even though very few state polls have been conducted on views of the A.H.C.A., we are able to estimate views on the bill in each state using a statistical method called M.R.P. (multilevel regression and postratification) and eight national polls that the Kaiser Family Foundation, YouGov and Public Policy Polling shared with us on people’s views on the A.H.C.A.

While no polling system is infallible, our M.R.P. model combines respondents’ demographic characteristics, their state and their views of the A.H.C.A. to estimate the probability that a voter of a certain age, race and gender, and in a state with certain characteristics, would support the proposal. It then estimates support for the bill within every state based on each state’s demographics. Models like this have been used to accurately predict public opinion in states on other topics, and in last week’s election in Britain.

We found that Republicans have produced a rare unity among red and blue states: opposition to the A.H.C.A.

For example, even in the most supportive state, deep-red Oklahoma, we estimate that only about 38 percent of voters appear to support the law versus 45 percent who oppose. (Another 17 percent of Oklahomans say they have no opinion.) Across all the states that voted for President Trump last year, we estimate that support for the A.H.C.A. is rarely over 35 percent. A majority of Republican senators currently represent states where less than a third of the public supports the A.H.C.A. By comparison, President Trump received 33 percent of the vote in Massachusetts.

How many senators might lose their seats as a result of supporting the bill? A recent study found that Democrats who supported Obamacare lost about six percentage points in the vote in 2010 — a dangerous omen for the 15 sitting Republican senators who won their most recent elections by less than that number. For example, if the A.H.C.A. costs Republicans as much support as Obamacare cost Democrats, senators like Jeff Flake of Arizona and Dean Heller of Nevada might be in danger of losing their seats. We estimate that only 28 percent of the public in Nevada supports the A.H.C.A., while only 31 percent of Arizonans support it.

With this said, it’s hard to know just how politically damaging supporting the A.H.C.A. would be. On the one hand, no major bill this unpopular has passed in decades, but some voters might forget about the A.H.C.A., or change their opinions, by the time some senators face re-election.

But the picture of public support is bleak in the home states of many reported G.O.P. swing votes on the bill. In Susan Collins’s Maine, Lisa Murkowski’s Alaska, Mr. Flake and John McCain’s Arizona, Cory Gardner’s Colorado, Bill Cassidy’s Louisiana, Rob Portman’s Ohio, Lindsey Graham’s South Carolina and Mr. Heller’s Nevada, we estimate that public support is under a third, and clear pluralities oppose.

With A.H.C.A. support in the subbasement, Republican senators have indicated they hope to make changes to the law. Although we can’t be sure exactly what they will change or how it might influence public support, the YouGov data indicate that Republicans in the House had little success softening the public’s opposition with their own modifications. In fact, support for the A.H.C.A. was even lower in the three YouGov polls after the House made its changes than in the two YouGov polls conducted before it.

Cynics might worry that senators care too much about their donors or primary voters to pay heed to general public opposition in their states. But evidence shows that when politicians learn that a majority of their constituents oppose a bill, many change their votes as a result. In one study, academics randomly assigned some legislators to receive information on public opinion in their districts, and found that legislators were much more likely to vote along with constituency opinion when they were informed of it.

But critics of the bill shouldn’t assume Republican senators know where their states stand. Research shows that politicians are surprisingly poor at estimating public opinion in their districts and states, Republicans in particular. G.O.P. politicians tend to overestimate support for conservative health care views by about 20 percentage points — meaning Senate Republicans might see their states as just barely supporting the A.H.C.A. Our analysis indicates this view would be mistaken.

[Christopher Warshaw is an Associate Professor of Political Science at M.I.T. You can follow him on Twitter at @cwarshaw. David Broockman is an Assistant Professor of Political Economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.]

Spread the word