When you combine 19th Century Man and 21st-century powers, you get U.S. President Donald Trump. And when you refuse to accept Trump, you get the most amazing phenomenon of the week: the public stand of the Joint Chiefs of Staff against their commander in chief.

This is unprecedented in U.S. history. Never before have the generals and admirals been so united. There was a “revolt of the admirals” against the reduction of naval forces over air force bombers; and the Joint Chiefs of Staff worked together against Chairman Colin Powell and President George H.W. Bush on the issue of tactical nuclear weapons in the ground forces.

But there is no precedent for this united front, a calculated provocation against the president who is capable – legally and temperamentally – of dismissing them all, even if it also means the resignation of Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

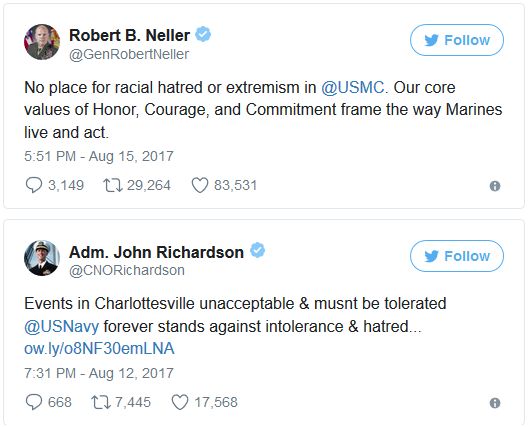

Tweets instead of obedience: that’s what Trump received from the chiefs of staff of U.S. Naval Operations, the Marine Corps, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Air Force, along with the head of the National Guard this week.

It’s all the fault of the Bavarians, of course. They deported Trump’s grandfather, Friedrich, back to the country to which he had immigrated when they discovered he hadn’t done his military service. Had the grandfather not returned to America, the Trumps would have remained in Germany. It’s fascinating to wonder with whom they would have identified during Hitler’s reign.

Donald Trump, who was born a year after the end of World War II, grew up in the home of a real estate mogul who was known for discriminating against black tenants. When Trump declares “Make America Great Again” or wears his red hat with the slogan in white letters, his intent is clear: to make America white again. Had he traveled in a time machine back to the American Civil War, he would no doubt have preferred to be Jefferson Davis – president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865 – rather than Abraham Lincoln, who freed the slaves.

There’s a great irony in Trump’s clash with senior army officers over his comments about events in Charlottesville. Trump, who with his aching feet evaded the draft during the Vietnam War, revels in the military atmosphere. He’s an armchair strategist whose armchair happens to be located in the world’s most important office.

There, he plays the general and coins alliterative phrases like “fire and fury” and “locked and loaded.” Yet he is now the target of fire and fury from the very officers he so admires – and while he is still taking pleasure in those who embrace the legacy of the South’s rebellion 150 years ago, he himself is the subject of a rebellion (if only a verbal one).

That’s not an obvious development, because the U.S. military is by nature conservative, somber, sanctifying of tradition. All the social changes to which it has become accustomed were forced on it from the outside, by presidents or congressional legislation. Even when it spearheaded change, it didn’t volunteer but was dragged into it by orders.

It’s hard to break down the divisions between branches of the armed forces, between officers and soldiers, between men and women. And the military is still basically a Southern organization. The Southern states are disproportionately represented by the location of bases, camps and headquarters. The Pentagon itself; senior officers’ residences; Joint Base Langley Eustis; the Atlantic Fleet in Norfolk, and more – all are in Virginia. The same is true for North and South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida. And most of the bases there are named after Confederate generals – enemy commanders in the Civil War.

There are two main reasons for this: family dynasties of the generals of George Washington, a Virginian, up to the fourth and fifth generation; and congressional power to appoint, budget and maintain bases – to provide employment for local voters – even when they are unnecessary, and maintaining them means less money for more important security activities.

The South rarely defeated veteran legislators, old and even very elderly, whose status helped their constituents. The separate arms of the military were proud of their patrons – congressmen from Virginia and Georgia. And they, because of the Civil War and Lincoln the Republican, belonged to the Democratic Party, which contained the contradictory trends of Northern and Western openness and Southern racism.

That was the situation facing Democratic presidents. When Lyndon B. Johnson wanted to soften the strong opposition of Democratic senators to legislating civil rights, he had to take into account that they were the strongest supporters of the Vietnam War. He had to choose his priorities: Social progress won, but lost him the presidency.

Because Southern Democrats were identified with the very worst kind of racism, in the early 1930s Franklin D. Roosevelt had the brilliant idea of creating a political alliance among all the ostracized – blacks, trade union members, Catholics (Irish, Italians), Jews. His victory ended 12 years of Republican rule. During World War II, he forced the army to recruit black soldiers and include them in combat, not only in office jobs and auxiliary forces – nearly always in separate units, under white commanders.

Black Americans’ participation in the war helped justify their demand for freedom in a country that presumed to fight for freedom worldwide. In 1948 (and only after baseball had disbanded its “color lines”), President Harry S. Truman forced the army to end the segregation of races in its ranks. The army obeyed. This didn’t help black soldiers outside their bases in the South, where discrimination remained – not only in the Deep South, but also in a North-South border state like Maryland. When the commander of the U.S. Naval Academy discovered black naval cadets were being refused entry to bars in Annapolis, he whispered a threat to forbid white colleagues from visiting. The owners caved.

Black officers successfully commanded mixed battalions in Vietnam, but again it was a Democratic president, Jimmy Carter, who had to promote a slew of black officers to the ranks of general. Carter appointed Clifford Alexander as the first black U.S. Secretary of the Army, in 1977. Alexander ordered affirmative action regarding promotions of colonels to brigadier general, on the way to becoming major generals. As a result, experienced and sophisticated officers such as Colin Powell, who previously were fated to retire as colonels, were promoted to the highest positions – four-star generals.

Powell – national security adviser toward the end of President Ronald Reagan’s administration – remained in the army even when George H.W. Bush offered him the position of CIA chief or deputy secretary of state, and was eventually appointed chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. His winning personality and success in the 1991 Gulf War attracted the next generation of blacks who were mulling whether to study in a military academy for four years and serve for 20 to 40 years.

That didn’t change the military’s conservative nature – it merely updated the policy regarding women in combat units and gay people; the old discrimination against Jews had already disappeared, based on the promotion of David L. Goldfein and others. When Bill Clinton was elected the next Democratic president (a Southerner, like every president following John F. Kennedy – until Barack Obama broke the sequence), he encountered strong and uniform opposition by senior officers to the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” (DADT) policy on military service by gays, bisexuals and lesbians, which was permissive for its time (1994).

Young sergeants were impressed by the president; generals and colonels less so, and they remained rebellious. They were also angry at Clinton – and Dick Cheney and Newt Gingrich – who were all comfortably engaged in advanced studies while others of their age were mired between Saigon and Da Nang during the Vietnam War.

The U.S. military would collapse if black soldiers were to leave tomorrow in protest at tacit support for racists by their commander in chief: They comprise one in five in the ground forces; one in six in the Air Force and U.S. Navy; and one in 10 in the Marines. The military command cannot permit such a rift.

John Kelly is the first general to serve as White House chief of staff since Alexander Haig worked for Richard Nixon. Haig played a major role in transferring the government from Nixon, who resigned in 1974, to his vice president, Gerald Ford. Kelly may find himself in a similar situation between Trump and Vice President Mike Pence.

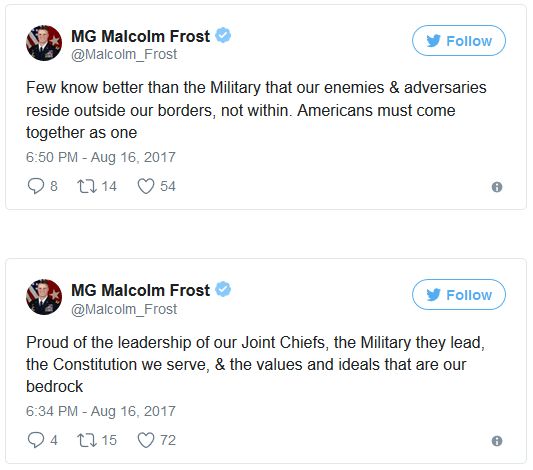

He who lives by Twitter falls by Twitter. All week, Trump has been increasingly under Twitter attack by the generals. Maj. Gen. Malcolm Frost, until recently the army spokesman, tweeted on Wednesday: “Few know better than the Military that our enemies & adversaries reside outside our borders, not within. Americans must come together as one. Proud of the leadership of our Joint Chiefs, the Military they lead, the Constitution we serve, & the values and ideals that are our bedrock.” Only one position, the highest, the source of all orders, was not mentioned.

This is a crisis of values the likes of which America has never known before, because it has never known a character like Trump.

____________________________________________

Amir Oren is a senior correspondent and columnist for Haaretz and a member of the newspaper's editorial board. He writes about defense and military affairs, the government and international relations.

Spread the word