Uber and Lyft's Effort to Disrupt Public Transportation Will Hurt the Environment and Screw the Poor

A 15-minute Uber ride or a 30-minute transit ride? For affluent city dwellers who increasingly prefer comfort and convenience, this choice is a no-brainer. However, this choice is a privilege that remains out of reach for those who live in transit-dependent low-income communities, who face many barriers to accessing ride-hailing services.

Uber competing with taxis is old news, but many now worry that ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft compete with public transit for riders. Not only can ride-hailing service be incredibly convenient, nowadays it can be dirt cheap, increasing the appeal of simply opening the mobile app. This trend may come as no surprise to cities with limited and inefficient transit that are losing their poor, transit-dependent riders in droves to gentrification.

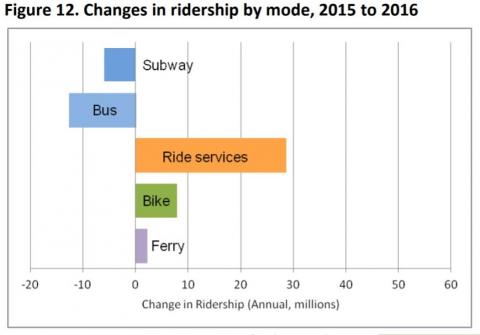

However, a 2017 study shows that even in New York City, Lyft and Uber ridership is increasing, as subway and bus ridership declines. When ride-hailing services threaten even the best public transit network in the country, you know we have a major problem. The graphs below show the changes in ridership by mode from the baseline of the previous year.

This drop in ridership and revenue indicates has made it harder for some cities to invest in public transit. Given this reality, cities may rely more heavily on shared mobility services such as bikesharing, carsharing, luxury commuter shuttles and ride-hailing services to replace public transit trips. Some public transit agencies are already testing this idea, and are providing subsidies to ride-hailing companies as a substitute to transit.

So who will be most harmed by less public transit service? Well, everyone who breathes dirtier air or sits in clogged traffic as transit use declines will be hurt, but transit-dependent low-income communities of color will suffer most. And city leaders can’t just ask these riders to replace their usual bus routes by downloading a ride-hailing app. Lyft and Uber don’t work for all demographics, especially those in rural areas, and those without access to banks or smartphones.

And while ridesharing fares have become cheaper over time, generally they are still much more expensive than public transit. While Lyft and Uber have vague “anti-discrimination” policies on their websites, there are no specific procedures to prevent discriminatory practices such as drivers going offline to avoid requests in lower-income areas.

A study showed that African-Americans faced 30 percent longer wait times and were twice as likely to have their ride cancelled as their white counterparts. Before cities open the floodgates to shared mobility services—Uber and Lyft in particular–they must take smart steps to reduce the harm to transit-dependent communities of color.

San Francisco recently began taking proactive steps to address potential harms of shared mobility services by approving a set of Guiding Principles for Management of Emergence Transportation Services to be used in all decisions and policies relating to these shared mobility options, including ride-hailing, microtransit, bike and carsharing, etc. The principles cover ten categories, including equitable access, sustainability, congestion, fair labor practices, and the need to complement as opposed to competing with transit. This marks a step in the right direction in reigning in the shared mobility industry and ensuring equity and sustainability are meaningful parts of their business models.

While the shared mobility industry can play an important role in our transportation system, it must not be allowed to completely replace biking, walking, and clean public transit. Lyfts and Ubers contribute to congestion and pollution, and failure to regulate them enables the automobile addiction of cities worldwide. A report from New York City shows ridesharing companies have caused a net increase of 600 million vehicle miles traveled, resulting in a 3 to 4 percent upsurge in traffic. Duke University released a report concluding that a single-occupancy vehicle emits 89 pounds of CO2 per 100 passenger miles, while a full bus emits only 14 pounds.

Meanwhile, the rapid growth of electric buses and other clean technologies will only further increase the efficiency of public transit—strengthening the argument that public transit is cleaner and more efficient than Lyfts and Ubers, and therefore should be a top priority in transportation planning. That’s one of the reasons the No Uber Oakland campaign has made working with—and not undermining—public transit one of its demands of the ride-hailing giant.

Greenlining’s Mobility Equity Framework seeks to ensure that the business objectives of shared mobility companies do not eclipse investments in clean forms of transportation such as walking, biking, and public transit. Low-income communities of color need greater access to clean, affordable transportation options that serve as connectors to economic opportunity. This framework will prioritize clean transportation options that align with equity and sustainability goals, before hastily rolling out the red carpet for the shared mobility industry.

Hana Creger is the environmental equity coordinator at the Greenlining Institute. Follow her on Twitter @hanacreger.

Spread the word