Billy Graham saved my soul. In 1973, I was ten years old, growing up in a working-class clan in North Carolina, and I had a problem: I liked boys. Also, men. And even though my family's Methodist church served up the mildest form of Protestantism – no dire warnings about fornicators and sodomites and feminists from our pulpit – it was impossible not to know, from a million cultural cues and a fair number of spankings I'd received for "acting sissy," that this was not good. So when I heard that the world's most beloved televangelist was coming to Raleigh that September for one of his extravagant "crusades," I begged my parents to take me. It didn't take much. They knew what they were dealing with. Maybe Billy Graham could straighten out their boy.

Though Trump's hardly a model of Christianity, the vast majority of evangelicals say they'll vote for him — here's how he pulled that off

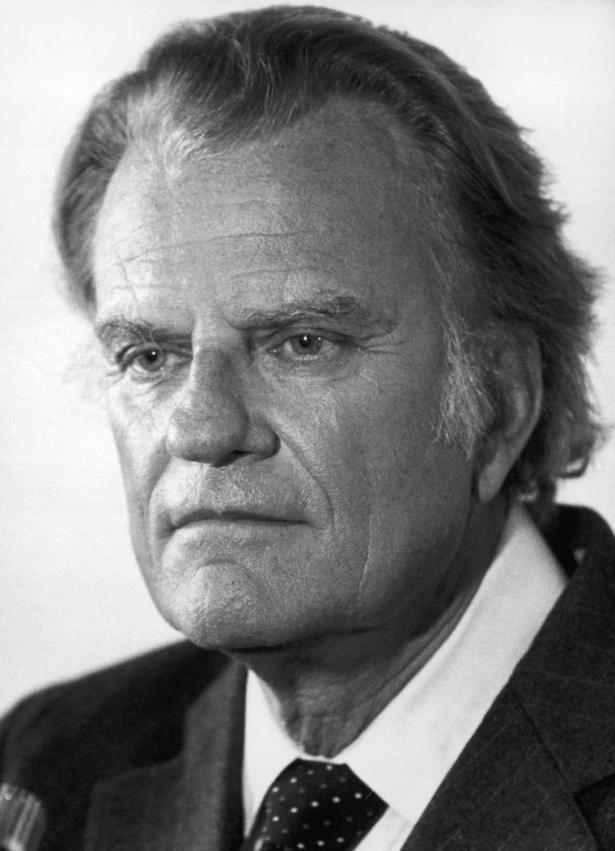

Graham was then at the apex of his powers, both religious and political. Since the late 1940s, when two of the country's most powerful publishers – William Randolph Hearst and Henry Luce – helped turn the ambitious blond hunk of North Carolina farmboy into a national celebrity, Graham had merged old-time fundamentalism with modern media to create a wildly popular civic religion. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association produced movies, radio shows, magazines and syndicated newspaper columns. Its crusades were television spectacles watched by millions of families like ours. They sometimes became headline news: Just a few years earlier, a single night of "crusading" in Seoul, South Korea, was attended by a jaw-dropping 1.1 million people. You might have called Billy Graham the rock star of Biblical literalism, except that he was bigger than Elvis and the Beatles combined.

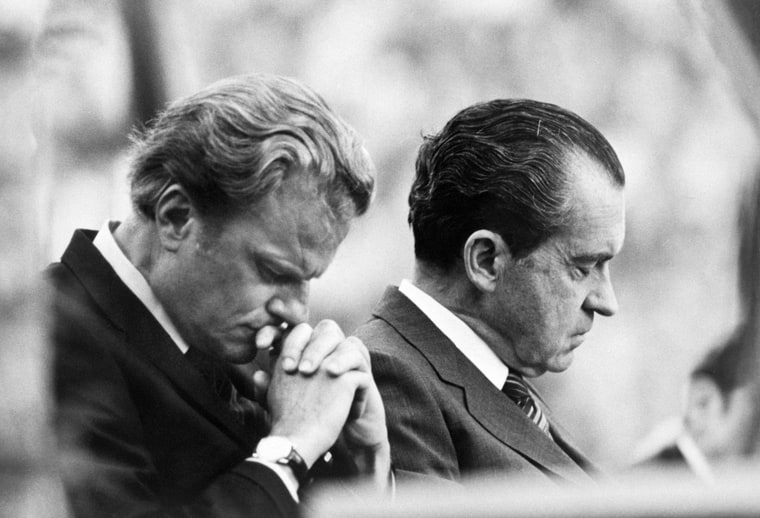

The Carolina Crusade of 1973 was held in N.C. State University's football stadium (no indoor arena could contain Graham's multitudes). His crusades were massive undertakings; staffers would move to a future host city three years in advance to organize and publicize, ensuring a maximum number of souls in the seats. The stands were nearly packed on the cool crisp night when we emerged from an hours-long traffic jam and took our seats for the show. I don't remember much about the singing and warm-up acts, nor the particular message Graham preached that night. And I had no idea that thanks to his long and tight friendship with President Richard Nixon, he was on the cusp of the one big public-relations disaster of his long and charmed career: According to newspaper accounts, Nixon's confidante was already, it seems, in damage-control mode. "This Watergate thing has become almost symbolic of everything that's wrong in America," he said. "And there's a little bit of Watergate in all of us. The Bible says all have sinned and come short of the glory of God. And I think we all have some repenting to do, including Billy Graham."

It would be years before anyone knew how much repenting Graham needed to do for his relationship with Nixon, or for his nefarious behind-the-scenes efforts to derail John F. Kennedy (because, Catholic) in 1960 and George McGovern (because, liberal) in 1972, or for the murderous advice he'd given both Lyndon Johnson and Nixon for conducting the war in Vietnam. None of it mattered to me, anyway. The man was here, in the flesh, and even from the distance of the bleachers he seemed bigger than life, radiant, a modern-day warrior Jesus ready to whip Satan's ass at a moment's notice.

Graham's performance was always much the same: He'd prowl the stage for 40 minutes or so, his resonant baritone lifting and lowering for effect, his huge hands chopping the air, offering a mix of corny jokes, op-eds on world and national events from a Biblical perspective, laments about the decay of American morality, and some of the most vivid images of hell and heaven, damnation and salvation, any preacher has ever painted. (In Heaven, he'd promised years before, "We are going to sit around the fireplace and have parties, and the angels will wait on us, and we'll drive down the golden streets in a yellow Cadillac convertible.")

I sat rapt and anxious throughout the proceedings, feeling a familiar guilty stirring of excitement as Graham repeatedly turned Jeeeeesus into the sexiest word you've ever heard. But the preachment was just a preliminary to the real action at any Billy Graham crusade; everything was leading up to the moment of truth, the "invitation." The big choir would start singing his signature altar-call hymn – "Just as I am, without one plea … O Lamb of God, I come, I come" – as Graham dropped his voice to a soft pleading purr: "If there is trouble in your life, if you're so weary you feel you can't carry on, then come on down and give your heart to Jesus and know what a full life can be. I want you to raise your hand and come on down. Just come, just come. See all the people giving their heart to Jesus, everybody giving their heart to Jesus…" At that signal (though I didn't know this either, at the time), paid staffers would start moving from the back of the stands toward the field, as if they were going down to be saved, so others would feel comfortable following suit.

My heart raced, my pants bulged, my head swam. I put up my hand, and, chaperoned by my father, headed down on shaky legs to be saved, along with thousands of others. Counselors were stationed around the stage, as Graham continued his seductive patter and the choir kept on singing. I repented, I confessed, I felt hands on my head, praying over me. I signed up to receive literature. And then it was over. I was born again. Everything would be different.

But nothing changed. The evil was still in me. And later that fall, I'd learn from Billy Graham just how evil I was. One morning in November, the local paper was open on the kitchen table when I went down to breakfast, turned to Graham's syndicated column, "My Answer." The headline was certainly eye-catching: "Homosexual Perversion a Sin That's Never Right." That day's question had come from a budding lesbian: "I'm a girl, and I love another girl!" wrote "M.D." "However, I am worried about my Christian life. My attention has been called to I Corinthians 6:9 [Neither the sexually immoral nor idolaters nor adulterers nor men who have sex with men...will inherit the kingdom of God] Please help."

Graham was happy to help. "Let me say this loud and clear!" he wrote. "We traffic in homosexuality at the peril of our spiritual welfare. Your affection for another of your own sex is misdirected, and you will be judged by God's holy standards." But there was hope! "You don't have to succumb to this insidious temptation," Graham wrote. "Reformation" is possible, he said. "Seize it while there's still a chance."

I have never known despair greater than I felt, reading those words. I had already tried to seize salvation, and it had eluded me. I would torment myself for another 20 years trying to find it, trying to "reform," dating women, attempting suicide, never quite able to shake the voice of Billy Graham promising me eternal damnation, even after I knew it was all a lie. Graham wasn't given to ranting about particular kinds of sins and sinners like Jerry Falwell or Pat Robertson. So when he was quoted elsewhere calling homosexuality "perversion that leads to death," it was no small thing for all of us confused kids out there. This was the voice of God on Earth, America's White Jesus, telling our parents that they were right to worry – and, if needed, to beat the gayness out of their child for the sake of his or her soul, or (worse) send them to "conversion therapy." And the voice was telling us that our loves and desires would, if pursued, land us in hell for eternity.

So spaketh the man who, upon his death on Wednesday at age 99, was almost universally lauded – just as he'd have wanted – as "America's pastor." A beloved figure of moderate and mainstream Christianity. A man who integrated his crusades in the 1950s, befriended Martin Luther King Jr. and infuriated the Ku Klux Klan. A trusted spiritual adviser to presidents, royals and celebrities. The rare evangelical superstar who eschewed partisan politics and never fell into moral disgrace. Or, as Barack Obama tweeted, "a humble servant who prayed for so many – and who, with wisdom and grace, gave hope and guidance to generations of Americans."

It's positively miraculous how Billy Graham's shiny reputation survived, intact, till the day he died – so much so that even a person as astute as Obama could laud him as an untarnished American treasure. But then Graham was, as a historian friend of mine commented the other day, a "stone hustler from the start," one of the greatest self-promoters ever born. Graham carefully cultivated a reputation for personal integrity and moderation, despite the fact that he was not only a virulent homophobe, but a few other not-so-Godly things as well: Jew-basher, aspiring war criminal, back-stabbing political operator and Christian Dominionist predicting imminent apocalypse, for starters.

The first thing that seemed to set Graham apart from the general run of fundamentalist preachers was his famous insistence, in the 1950s, on integrating his crusades. In 1957, during a historic crusade at Madison Square Garden in New York, Graham even invited MLK to deliver a prayer. "There is no room for segregation at the foot of the cross," Graham famously thundered. This gave him the halo he wore for the rest of his days. "He is on the plus-side of history," said the Rev. Jesse Jackson on hearing of Graham's death.

The reality was a good bit more complicated: Once the Freedom Buses started rolling South, and civil disobedience spread in the early 1960s, Graham's support for civil rights dissipated. When King wrote his famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail in 1963, Graham told reporters the Alabama preacher should "put the brakes on a little bit." He began to criticize civil-rights leaders for focusing on changing laws, rather than "hearts." He mocked King's "I Have a Dream" speech, saying, "Only when Christ comes again will the little white children of Alabama walk hand in hand with little black children." And he broke with King altogether over his opposition to the Vietnam War, which Graham enthusiastically championed.

Graham always insisted, contrary to all evidence, that he had no interest in politics. In truth, he was a Machiavellian back-room operator. In 1960, when Nixon faced John F. Kennedy, Graham said that if Kennedy was a real Catholic, he'd do whatever the Pope wanted him to do as president rather than follow the Constitution. Graham convened a meeting of Christian leaders in Montreux, Switzerland (among them was young Donald Trump's pastor, Norman Vincent Peale) to scheme about how to keep the Catholic out of the White House. Eight days later, Graham sent Kennedy a fawning letter, promising not to raise "the religious issue" during the campaign and vowing his ardent support if Kennedy won. After Kennedy's assassination, Graham flattered his way into a friendship with Lyndon Johnson – they once reportedly went skinny-dipping at the White House pool. But the minister's role was mostly to provide moral justifications for Johnson's escalation of hostilities in Vietnam.

In 1969, with his friend Nixon finally in the Oval Office, Graham advised him to try and end the Vietnam conflict in a blaze of glory, with a bombing campaign that Nixon himself estimated would kill one million civilians. This was too much even for Nixon, but not for America's Pastor. Graham provided a steady stream of military and political counsel to Nixon, including copious notes about campaign strategy in 1972.

When the tapes that sealed Nixon's doom came out, and the vulgarity and hatefulness of the president were revealed, Graham pronounced himself "shocked" at the kind of language the president used, in addition to his criminal behavior. It would be decades before tapes of Graham's own conservations with Nixon were made public. In brief conversations from 1972 and 1973, Graham comforts and cheers Nixon during his darkest hours, partly by engaging in anti-Semitic banter. The Jews, he told Nixon, were the ones "putting out the pornographic stuff." Prominent Jews, Graham said, "swarm around me and are friendly to me. They don't know how I really feel about what they're doing to this country."

On the 1972 tape, Graham and Nixon were talking about the president's reelection campaign. When Graham mentioned he had a meeting coming up with the editors of Time, Nixon aide H.R. Haldeman commented, "You meet with all their editors, you better take your Jewish beanie." Graham is heard laughing, and asking, "Is that right? I don't know any of them now." The conversation continued:

Nixon: "Newsweek is totally, it's all run by Jews and dominated by them in their editorial pages. The New York Times, The Washington Post, totally Jewish too."

Graham: "The stranglehold has got to be broken, or the country's going to go down the drain."

Nixon: "You believe that?"

Graham: "Yes, sir."

Nixon: "Oh boy, so do I. I can't ever say that, but I believe it."

Graham" "No, but if you get elected a second time, then we might be able to do something."

Whatever Graham and Nixon wanted to "do" with the Jews, Watergate got in the way. As George Will tartly concludes, "One can reasonably acquit Graham of anti-Semitism only by convicting him of toadying."

Nixon's downfall was only a temporary embarrassment for Graham, a small blemish on a sterling reputation. While publicly swearing off politics for good, he insinuated himself into the favor of Gerald Ford, then Jimmy Carter. When the Moral Majority came together in the late 1970s, turning evangelicals into a political wing of the Republican Party, Graham kept his distance – and made sure everyone knew it. It was another brilliant PR move. The truth, however, was that Graham made the new wave of evangelical politics possible. "Without him," says Randall Balmer, Dartmouth theologian and author of Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory, "we'd be living in a different world. … Evangelicalism today would have virtually no political or cultural relevance whatsoever."

Graham's special gift was portraying himself as a different kind of evangelical. The most famous and most heavily self-promoted Christian of the entire 20th century was big on promoting his humility, and his personal moral rectitude. He famously insisted that everyone call him "Billy." He refused to make himself insanely wealthy, taking only a comfortable (and publicly disclosed) salary from his organization. He instituted the "Graham rule" for himself and his associates – he'd never be alone in any room with any woman but his (long-suffering) wife, to avoid temptation and even the appearance of impropriety. It was a purposeful strategy to ignore the Elmer Gantry-ish excesses of the famous American evangelists who'd come before him. And it worked like magic. When scandals destroyed some of his imitators in the 1980s, like Jim and Tammy Bakker, Graham's operation looked even more like a model of rectitude in comparison.

But despite his showy flag-waving, despite the conflation of Christianity and Americanism that he trafficked in, Graham was no small-d democrat. Quite the contrary: He was an ardent theocrat. "Every type of government has been permeated with corruption, evil, and greed," he proclaimed in the wake of Watergate. "But there's one type we have not tried. That is a theocracy, with Christ on the throne and the nations of the world confessing him. Someday His flag will wave over every nation in the world."

Billy Graham reputedly mellowed and became more tolerant of religious differences in his later years, even as he turned over his vast empire to his more overtly bigoted son, Franklin. Maybe, he even suggested at one point, you didn't have to be a born-again Christian to attain heaven. But he never evolved on the "gay question." Quite the contrary, in fact. At a rally in 1993, he speculated that AIDS might be a "judgment" from God. "I could not say for sure, but I think so," he said. He knew this was bad PR, and two weeks later, he apologized. "I don't believe that," he claimed, "and I don't know why I said it." But he never disclaimed the infamous "My Answer" column from 1973, never took back his description of homosexuality as "a perversion that leads to death."

In 2012, in his last public act, Graham took out full-page newspaper ads in 14 North Carolina newspapers calling for passage of a law banning same-sex marriage. "At 93," he wrote, "I never thought we would have to debate the definition of marriage. The Bible is clear – God's definition of marriage is between a man and a woman." That same year, he met with Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential nominee, and pledged his support. Graham issued a statement that stopped short of endorsing Romney – he wasn't political, after all! – but made it clear enough: "I hope millions of Americans will join me in praying for our nation and to vote for candidates who will support the biblical definition of marriage, protect the sanctity of life and defend our religious freedoms."

Next week, Graham's corpse will lie in state at the Capitol rotunda – only the fourth private citizen to be so honored, and the first since Rosa Parks in 1995. This is a disgrace. But in a certain way, it's also right and fitting – as oddly appropriate as Graham's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. If Billy Graham was, ultimately, a conniving hypocrite with a layman's grasp of the Bible and a supernatural lust for earthly power, he was also a quintessential American success story. He was not so much "America's pastor" as its greatest evangelical entrepreneur – the man who launched a whole separatist (and lucrative) Christian media culture, who laid the foundations for megachurches and prosperity ministries, who brought Jesus back into American politics. He was a public-relations savant, a shameless sycophant who whispered sweet nothings to power in lieu of hard truths. He demonstrated what fortunes could be made, and what human glory could be attained, by transforming evangelical Christianity into a patriotic corporate entity. If that's not American, by God, what is?

Read more of Bob Moser's contributions to Rolling Stone here.

Spread the word