Why a Trespassing Trial This March Has Caught the Attention of Activists on Both Sides of the Abortion Movement

On the first Saturday in December, patients were arriving at the Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic in Virginia. At the Big Lots! parking lot across the street, about a dozen anti-abortion activists prayed in a circle. If all went according to plan, they’d spend at least part of that day in jail.

“From the fear of being wrong, deliver me, Jesus,” they prayed, repeating after Lauren Handy, who calls herself a “Catholic anarchist.”

“I don’t recognize the civil authority of government, only God’s authority,” she would tell Rewire about a month later, at her first court hearing over the trespassing charges she incurred that Saturday.

The activists crossed the street until they reached the clinic, which offers first- and second-trimester abortions in addition to gynecological care. Handy took red roses, as did activists Linda Mueller and Michael Webb. The roses came with little notes that read, in part: “A new life, however tiny, brings the promise of unrepeatable joy.”

As Handy tells it, the trio entered the clinic. They tried to hand roses to patients in the waiting room, as clinic staff ushered patients to another room, trying to avoid the protesters. The activists prayed out loud, begging women to cancel their appointments, and refused to leave. When police arrived to arrest them for trespassing, they went limp, forcing officers to carry them out in wheelchairs or on stretchers.

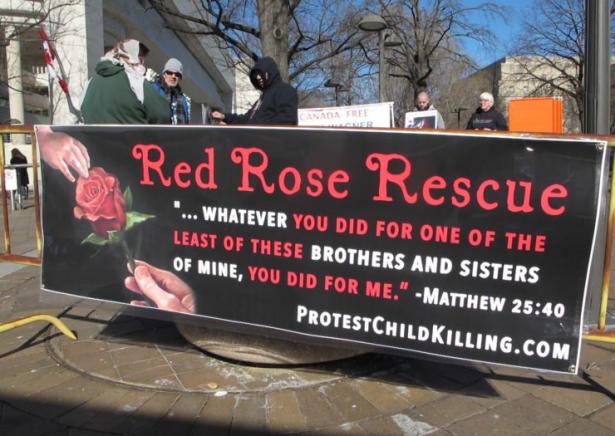

Such was the second-ever Red Rose Rescue, the latest effort from the militant corner of the anti-abortion movement that’s ultimately trying to bring enough chaos to clinic waiting rooms and parking lots to interrupt access to care.

So far, they have staged coordinated protests inside five clinics in five different cities. Their new tactic, which officially debuted last September, is loosely based on an old one. At its height in the late 1980s, the so-called rescue movement’s goal was to stop access to reproductive health clinics. In practice, activists used their bodies to blockade clinics, glued door locks, and, in a few cases, bombed facilities and killed staff.

The Red Rose Rescuers are taking a decidedly softer approach: Rather than physically preventing patients and staff from getting through doors, they are walking in, refusing to leave, and trying to engage with patients about to have abortions. They say they’re effectively bringing the ubiquitous tactic known as “sidewalk counseling”—where activists stand on the sidewalk outside of clinics and try to persuade women not to get abortions—inside.

But many of the participants in this new tactic come from that older rescue school. This crop of Red Rose Rescuers combines millennials like Handy, who is 24, with veterans of the old movement, some of whom in the past engaged in radical tactics, such as destroying clinic property and stealing fetal remains from pathology labs.

Organizers told Rewire their goal is to bring Red Rose Rescues to reproductive health clinics all over the country, all of the time.

But first, they are waiting to see how courts start ruling on their tactics, organizers told Rewire. Several of the activists who staged direct actions at clinics in September and December 2017 have since faced misdemeanor trespassing, obstruction of justice, and unlawful entry charges, all of which have thus far either been dismissed, or resulted in probation and/or small fines. In some of the cases, activists have appealed their convictions to higher courts. The next round of trials, at which Handy and Mueller will face misdemeanor trespassing charges, will take place in Alexandria, Virginia, on March 9.

Providers and advocates worry that if courts continue to respond with what they believe are mere slaps on the wrist—and if they disregard the past criminal records of some defendants—clinic staff and patients will see an increase in harassment and intimidation. Already, they have been on edge since anti-choice extremist Robert Lewis Dear Jr. shot up an abortion clinic two-and-a-half years ago, killing three people. Additionally, providers have been reporting rising rates of threats and vandalism in recent years, in part, they say, because of increased political rhetoric against abortion rights. Just in the last month, one extremist threatened to blow up a clinic in Indiana, and another drove a truck through a Planned Parenthood clinic in New Jersey, injuring three people, including a pregnant woman.

In interviews with Rewire and in public statements, the Red Rose Rescuers insist their intentions are peaceful. Nevertheless, some of the organizers’ backgrounds and thirst to return to the rescue days worry providers and advocates, who believe the Red Rose Rescuers could incite future violence at clinics.

“These are very dangerous developments,” said duVergne Gaines, who directs the Feminist Majority Foundation’s National Clinic Access Project, which works to help ensure safety for patients and providers at reproductive health clinics.

Advocates also see the protests as clear violations of the federal Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act, which was designed to protect access to clinics and make it a federal crime to use tactics like clinic blockades, intimidation, and threats of force.

“They try to maintain them as innocent as much as possible,” Gaines said. “But they are inviting people—anyone, especially individuals that may have violent inclinations—to breach the private interiors of these facilities, where patients and physicians and clinicians and administrators and other individuals are. It is illegal. It is dangerous and should not be whitewashed.”

Bringing Rescue Back

The Northland Family Planning Center in Sterling Heights, Michigan, offers a range of reproductive health services. According to its website, it tests for and treats sexually transmitted infections, provides birth control, offers urgent care when patients need immediate treatment for problems like bladder and urinary tract infections, and provides abortion care up to 24 weeks’ gestation.

On the morning of September 15, 2017, four activists arrived at Northland’s waiting room. Outside, other anti-abortion activists circled the building with video cameras and narrated the inaugural Red Rose Rescue.

That same morning, four women and two priests walked into the Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic—the one that would be targeted a second time in December. The protesters wouldn’t budge when asked to leave.

The third protest, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was the only one that didn’t end in arrests. Two activists entered the University of New Mexico Center for Reproductive Health, which trains future OB-GYNs to perform abortions. But they fled before police arrived, according to a blog post by the coordinators of the action, Bud and Tara Shaver.

All arrested activists were released on their own recognizance, and many returned to these same clinics that very day and resumed picketing outside.

Less than three months after the first Red Rose Rescue, three more groups—consisting of many of the same people—repeated the actions, this time in Washington, D.C.; West Bloomfield Township, Michigan; and again at the same clinic in Alexandria.

After they were released from jail later that day, Handy and her group relocated to the sidewalk outside Capital Women’s Services in Washington, D.C., where they loudly sang as police carried out Fr. Stephen Imbarrato, Julia Haag, and Joan McKee.

The video anti-choice activists shot displays a frenetic scene. In a blog post on the clinic’s website, staff describe their patients’ fear and discomfort.

“On Saturday, December 2nd, Capital Women’s Services was infiltrated by anti-choice militants who harassed, demeaned and disrespected our patients and who physically prevented our medical staff from entering our facility,” the post reads. “Due to the actions of these criminals, our patients were left feeling scared, frustrated, humiliated and demeaned. They deserved better than the judgement and harassment leveled at them by people who refused to acknowledge the humanity of our patients.”

The Red Rose Rescuers are tight-lipped about their specific plans going forward, but it is clear that these actions have been the result of intense planning and coordination. And what’s also clear is that even in the face of recent trespassing convictions, these activists are trying to expand their actions, not back down.

A theology professor at Michigan’s Madonna University and the director of Citizens for a Pro-Life Society, veteran activist Monica Migliorino Miller is one of the Red Rose Rescue movement’s main founders. She told Rewire in an interview this January that she is currently trying to expand the network of Red Rose Rescuers by finding new regional leaders to run local branches.

And in February, Miller made an appeal for more rescuers, on a radio show hosted by anti-abortion leader Mark Harrington, saying that in order to continue the actions, they needed people “willing to lay down their lives and be there.”

Even if you don’t recognize Monica Migliorino Miller’s name, you probably recognize her work, if you’ve been anywhere near a reproductive health clinic in the last 20 years.

Many of the images of fetuses displayed on giant posters that protesters wield outside of clinics across the United States every day are derived from fetuses that Miller, with the help of prominent activist Joseph Scheidler and others, took from the trash barrels of a Chicago pathology lab in 1988. As has been documented by historian Johanna Schoen in her 2015 book Abortion After Roe, these activists routinely broke into this pathology lab over a period of nine months and stole around 5,000 fetal remains waiting to be picked up for incineration.

As she told the New York Times a few years ago, Miller stored these remains in her apartment in Michigan so they could be photographed and used for future anti-abortion literature. She would eventually bury them in a cemetery.

She acknowledged to the Times that many of the fetuses appeared to be older than when most abortions occur.

Miller has not always denounced violence made in the name of anti-abortion activism.

During a hearing related to trespassing at Wisconsin clinic in 1993, Miller told the court, “If a police officer is escorting a woman into an abortion clinic and somebody were to shoot the police officer, I could not say that pro-lifer did something immoral.”

What she was talking about is the idea of “justifiable homicide”—that killing a provider or a clinic volunteer or security guard who is assisting in an abortion can be justified if the reason was to save a life.

Decades after that statement in court, Miller published a book in 2012 titled, Abandoned: The Untold Stories of the Abortion Wars. In it, Miller calls her “first musings” on justifiable homicide “hasty and imprudent.” She writes that she resolved that “the tragedy of abortion can only ultimately be resolved through non-violence.”

A year prior, at a freezing-cold March for Life-related rally, Miller had called for abortion opponents to get more militant.

“To stop abortion, to be involved with this injustice, to want to see it end, you can’t live a normal life anymore,” Miller told the crowd who had gathered that day in front of a Planned Parenthood clinic that was still under construction, as reported by Robin Marty, for DAME magazine.

“On the day that this death mill [the D.C. Planned Parenthood] will open, will there be anybody here, will somebody lay their body in front of the door, will you handcuff yourself to construction equipment? Come on guys, think about it, let’s be creative, what are you willing to do to stop this place from being built?”

For a year, Miller carried that sentiment with her. Finally, in 2017, she started emailing fellows of the former rescue movement to join her in a resurgence of this tactic.

“That’s the key to growing the rescues themselves, if local leaders are able to recruit and plan efforts,” Miller told Rewire outside of the Canadian embassy, where she and a few fellow Red Rose arrestees had gathered to protest the fact that Canadian anti-abortion activist Mary Wagner, their movement’s inspiration, is back in jail in Toronto for violating the terms of her probation.

Health providers and advocates are concerned that, in addition to the immediate disruption to services, anti-choice activists are potentially reviving a tactic that so limited access that the federal government created a law to specifically defend the right—not just to have an abortion, but to be able to enter clinics that offer it.

In the 1980s and early ’90s, there were thousands of activists willing to carry out so-called rescues, which often involved staging human blockades in front of clinic entrances, gluing the locks of clinic doors, and destroying medical equipment. In short, their goal was not just to protest, but to physically prevent individual abortions.

Activists maintained the movement’s intentions were peaceful and nonviolent, though it is clear that providers and patients felt differently. And their tactics did attract some violent extremists. Some started using bombs and guns to accelerate the movement to end abortion access.

In 1994, following a series of clinic bombings and shootings, Democratic President Bill Clinton signed the FACE Act into law. FACE made it a federal crime to try to prevent someone from accessing medical services at a reproductive health clinic by physically blocking the entrance to a clinic, or by using the threat of force or intimidation to prevent providers from doing their jobs.

So while picketing remains a day-to-day reality at most abortion clinics across the United States, the law effectively tamped down this more radical “rescue” tactic.

Now, however, these activists are currently trying to figure out what they can get away with before triggering a lawsuit under FACE or similar state laws.

Red Rose Rescuers are not the only activists to attempt to reintroduce rescue tactics to the anti-abortion movement. But the organizers behind the Red Rose Rescues argue that their actions do not violate the FACE Act because they are not physically blocking access to clinics.

From day one, Miller was quick to point out in her video that “the Red Rose Rescues did not block the doors to the abortion center or the hallway leading to the procedure rooms.”

Handy told Rewire the same thing: They are not blocking entrances. But elsewhere, she’s admitted their intentions are to halt operations at abortion clinics.

“As long as I was in there, abortions couldn’t be performed,” Handy said during a January radio appearance on the Pilgrim’s Progress Radio Broadcast, talking about her December Red Rose Rescue. “And so, it gave the mothers longer opportunity to change their mind.”

Asked by Rewire to respond to that point—that she knew she was disrupting services—Handy said she can’t control others’ actions.

Miller told Rewire that the point of the Red Rose Rescues is not about challenging FACE. Though in the same breath, she added, “If that opportunity presents itself, then we will.”

Meanwhile, abortion-rights advocates like Gaines fear the return of the rescue days. She argues that these actions—however peaceful their stated intention—could motivate extremists to enter clinics with violent intentions. She believes they are unquestionably FACE violations.

“It’s intimidation and terror and disruption, which is actually what the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act was designed to combat, especially when these clinics are being targeted in a concerted effort across state lines, which is what you have here,” Gaines said. “This is an effort to intimidate and terrorize abortion providers and the patients they serve.”

Gaines said that the Feminist Majority Foundation’s National Clinic Access Project—along with the National Abortion Federation, Planned Parenthood, and law-enforcement agencies—is trying to provide security and safety help to clinics.

“Our goal is to do everything we can to prevent this from happening and to prevent violence from happening,” Gaines said. “When you are actively encouraging other people to breach, to trespass into a facility—I mean, how dare they? How dare they, considering Robert Lewis Dear happened not long ago? It’s outrageous that they would believe that they are operating in an atmosphere of impunity.”

The core group that has revived the rescue technique are practiced protesters unafraid to risk prison time or penalties to further that cause. They are fundamentalists, and they are frustrated with the pace of the anti-abortion movement thus far.

“The engineers of this so-called Red Rose Rescue are not just any Joe, Dick, and Harry,” said Gaines. “Their hands are unclean.”

Miller essentially shrugged when asked to respond to fears of abortion-rights advocates that these actions could encourage extremists to arrive at clinics with the intention to harm providers and patients, as Dear did in 2015 when he stormed a Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs and fatally shot three people. Soon after, he declared himself a “warrior for the babies.”

“I think that’s rhetoric,” Miller said. “I think that they are overacting. And I don’t believe it’s going to come to that.”

The Legal Strategy Behind the Protests

So far, the protesters in each misdemeanor trespassing case have turned down plea deals. They’ve all pleaded not guilty, but their objective is not so much to avoid penalties but to make a controversial legal argument in court.

Known as the “necessity defense,” this is the argument that unlawful activity is justifiable because it will prevent an imminent, more serious harm than the unlawful activity in question. For example, a woman who drove drunk to escape her allegedly abusive husband used the necessity defense in a 2013 case in Minnesota.

Many jurisdictions do not recognize this defense, and in general it’s a very difficult argument to be allowed to use, let alone win with. A rare example where the necessity defense was deployed successfully is the case of Texan Tim Stevens, who in 2008 was acquitted of marijuana possession charges after his attorney argued he needed the marijuana to relieve a severe vomiting illness associated with his HIV infection.

Joan Andrews Bell, at 70, is among the seasoned veterans of the rescue movement and has been arrested hundreds of times. Notably, she employed notorious anti-choice sniper James Charles Kopp before he went on a murderous spree targeting abortion providers.

As journalist Jon Wells writes in his 2013 book, Sniper: The True Story of Anti-Abortion Killer James Kopp, in 1997, Kopp worked as a volunteer at Good Counsel Homes, a home for single mothers based in Hoboken, New Jersey, which Bell founded with her husband, Chris. According to Wells, Bell was actually one of Kopp’s “earliest inspirations in the movement.” He writes that Kopp was inspired to join the rescue movement after Bell entered an abortion clinic in Pensacola, Florida, in 1986 and tried to tamper with medical equipment. She was sentenced to five years in prison for that offense, and ended up serving about half that time.

Kopp befriended Bell and began participating in rescues that involved blockading and vandalism. By 1998 his tactics took a fatal turn when he hid in the woods behind Dr. Barnett Slepian’s home in upstate New York and killed the OB-GYN with one shot.

Bell participated in the September rescue at the Alexandria clinic. But she’s actually been trying to rekindle the rescue movement on her own, for the past decade.

In 2009 Bell started a training camp for future rescuers called Gethsemane, named after the garden in New Testament where Jesus is said to have frequently prayed with his disciples, including the night before he was crucified.

The number varies from year to year, but Bell told Rewire that there’s usually a handful who stay at her farmhouse every year. They learn the tactic, she said, and they commit to resisting arrest at clinics for an entire year.

Still, anti-abortion protesters have been trying to use the “necessity defense” in court for decades to attempt to justify a range of crimes committed in the name of their anti-abortion ideology, from trespassing at clinics to murdering doctors. These activists argue that abortion is murder and thus a more serious harm than trespassing, destroying the private property of a clinic, or even killing a doctor who provides abortion.

Judges rarely accept such arguments. And if history serves, Red Rose Rescuers are unlikely to be acquitted using the necessity defense. However, part of their goal is simply to be able to make that case in public.

Handy said this is “part two” of the Red Rose Rescues. Part one is the “public witness” in front of clinic patients, police, street passersby, and the media. Part two, she said, is public witness in the courts. And part three, when rescuers are sent to jail, is public witness in jail, to explain to other prisoners their anti-abortion ideology.

So far, courts have found Red Rose Rescuers guilty of trespassing in four out of six trials—with several of the defendants facing similar charges from multiple actions.

Last November, the six protesters that resisted arrest at the Alexandria clinic in September were the first among the Red Rose Rescuers to go to trial. They were charged with obstruction of justice and trespassing, both misdemeanors. The judge dismissed the obstruction of justice charges for all six defendants but found each guilty of trespassing, which according to court records, carried one year of unsupervised probation and $89 in court fees. According to Handy, who was present at the court that day, the defendants’ attorney, Chris Kachouroff, tried to argue that the protesters acted out of necessity. The judge listened but refused to consider the argument, saying it was inapplicable to the trespassing charge, she said.

In early February, Michael Webb was found guilty by a different judge in the same Alexandria General District Court for his Red Rose Rescue at the Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic in December. Handy and Mueller were present at the same rescue as Webb, but their trial was postponed until March 9. Webb has appealed the decision to the Alexandria Circuit Court.

Also in February, a six-person jury convicted protesters who participated in the September 2017 Red Rose Rescue at the Northland Family Planning Center in Michigan of trespassing and sentenced them to two years of non-reporting probation. Following the trial, Miller told the Macomb Daily that she will continue organizing Red Rose Rescues in spite of the probation sentence, even though that could have legal ramifications.

As the newspaper reported, the defendants—Matthew Connolly of Minnesota, Will Goodman of Wisconsin, college student Abby McIntyre of Indiana, and Miller—have appealed the conviction on the basis that the judge rejected their necessity defense.

However, the judge did allow each defendant to make a statement explaining why abortion is murder and why their actions were necessary. And that, in itself, is a win, activists say.

After a preliminary hearing in Handy and Mueller’s case at the Alexandria General District Court in Alexandria, their attorney, William Hassan, huddled with his clients and about a dozen activists who had come to court in solidarity with their fellow Red Rose Rescuers.

“Expect the hearing to be anticlimactic,” he told the group, referring to their forthcoming trial in March. “They’re still going to convict. The point is to get this on the record, why we were there.”

The group that participated in the second Michigan-based Red Rose Rescue, which includes Connolly, Goodman, and Miller, as well as Robert Kovaly and Patrice Woodworth, were also convicted of trespassing and await sentencing, which is scheduled for March 14, according to the Oakland Press News. The Press News reported that as a condition of their bond, the five defendants in this case can have no contact with reproductive health clinics unless it is to seek medical advice.

But, as the Press News reported, this time the judge had not allowed Miller and the other defendants to testify about abortion as part of their defense.

For the three protesters who have been charged with unlawfully entering Capital Women’s Services in Washington, D.C., in December, their lawyer is also planning a necessity defense for their trial, which is scheduled for June. Judge Frederick Weisberg will rule on whether to accept this argument at a pre-hearing trial scheduled for May.

During a preliminary hearing in February, the three defendants rejected plea offers where probation would be waived on the condition they agree to stay away from this clinic. Weisberg appeared to be somewhat sympathetic to the protesters. He called their actions “a matter of conscience.” And on agreeing to delay the trial at the defense attorney’s request, Weisberg said, “You don’t worry about a danger to the community in a case like this.”

On the other hand, Weisberg balked at defense attorney Paul Kiyonaga’s request to present witnesses at the pre-trial hearing to make the case for why he should either be able to argue the necessity defense or what he called the “belief defense.”

“I doubt I would need an expert witness to tell me the law,” the judge snapped.

But the big legal question that remains in all of this is whether these Red Rose Rescuers will be charged under the FACE Act. Both the supporters and critics of this movement believe its growth hinges in part upon that question.

The Department of Justice (DOJ), currently under the leadership of Attorney General Jeff Sessions, an outspoken opponent of abortion rights, has not publicly acted on the Red Rose Rescues. The DOJ declined to comment for this story.

Critics of this movement actually include anti-abortion organizations.

Just last week, the group Sidewalk Advocates for Life published a 20-minute video condemning the Red Rose Rescue movement, and other types of rescues, as strategically and legally reckless for the movement at large. The video features former clinic workers who have since become organizers within the anti-choice movement, who describe what these Red Rose Rescuers are doing as likely terrifying from the perspective of the patients. The video also quotes legal experts who advocate on behalf of anti-choice causes, such as Albuquerque-based attorney Michael Seibel, who warns that just because the DOJ has not yet filed a federal lawsuit against Red Rose Rescuers doesn’t mean they won’t.

“Why haven’t they done anything about the FACE Act yet?” Seibel asks, referring to the DOJ. “Most likely it is to rope in as many pro-life organizations as possible in order to limit their activities. Twenty-two years as a trial lawyer tells me, I’m going to wait until they keep doing it over and over and over and over again because there’s a five-year statute of limitations the way I read it on the FACE Act. So, they could bring this up to five years later.”

Indeed, it remains to be seen if, when, and how the DOJ will respond to these actions. But one thing that seems clear is the Red Rose Rescues are not happening in a vacuum.

There appears to be a growing restlessness spreading across certain corners of the anti-abortion movement. The past two decades have been dominated by efforts to limit abortion access via state legislatures and the courts. As Rewire’s reporting frequently demonstrates, these legislative efforts have successfully hindered access to legal abortions. But anti-abortion activists like Joan Andrews Bell, Handy, and Miller think change is moving too slowly.

And they are not the only collective of individuals to feel this way.

Last May, in Louisville, Kentucky, about a dozen activists associated with the Texas-based group Operation Save America (OSA) kneeled on the concrete in front of EMW Women’s Surgical Center, physically blocking access to the clinic’s door. (Rewire took a deep dive into OSA’s history and forward-looking strategy in our recent audio documentary Marching Toward Gilead.)

Initially, the protesters only faced local trespassing charges, which were subsequently dropped. Rusty Thomas, OSA’s president, told Slate‘s Michelle Goldberg last July that he had wanted to see what kind of friend he had in Trump’s administration. He said that he was pleasantly surprised to see no charges from the Justice Department.

But they came.

On July 17, 2017, the DOJ charged ten individuals with multiple felony counts under the FACE Act.

The case is ongoing. At a preliminary hearing on July 24, during the same week of OSA’s national event held also in Louisville, Assistant U.S. Attorney Jessica Malloy, representing the DOJ, tried to build a case that Operation Save America had effectively intimidated clinic staff and patients. She asked one of the witnesses, a young woman referred to in the case by the pseudonym Jane Doe, about her experience approaching the clinic for an early morning appointment and seeing the door blocked by a dozen protesters.

With tears, Doe recalled what some of the protesters told her as she approached: “‘You’re already a mother, and you’re making a terrible decision.’”

“It was hard,” Doe explained. “It made you feel sad. It was stressful. It was intimidating. It was already difficult.”

She said the situation was “scary,” adding, “I’m not very big.”

Sofia Resnick is an investigative reporter for Rewire. She has uncovered abuse and exposed religious influence on academic research and public policy in the areas of reproductive health and LGBT discrimination. Prior to joining Rewire, Resnick was an investigative reporter for the American Independent, an online publication based in Washington, D.C. She has worked for the Austin Chronicle in Austin, Texas. She has a master’s degree in journalism from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

Spread the word