WASHINGTON — Seymour M. Hersh didn’t even want to write a memoir.

He had been on contract for a book about Dick Cheney, the former vice president. He had spent four years reporting it, amassing dozens of files of what he called explosive material, only to find that his sources had gone jittery amid a government crackdown on leakers. He went to his publishers at Alfred A. Knopf, “hat in hand,” and said he couldn’t go through with it. He offered to mortgage his Manhattan pied-à-terre to repay the advance.

“They said, ‘Write a memoir,’ and I said, ‘No way,’” Mr. Hersh, 81, recalled the other day. “I don’t write about my family, and I never do.”

Plus, the Sy Hersh story — the story of a working-class Jewish kid from the South Side of Chicago, who through serendipity and toil had exposed the horror of the My Lai massacre, revealed domestic and foreign abuses by the C.I.A. and harried Washington’s elite for a half-century — was not finished.

“I’m still doing it,” Mr. Hersh said, sounding both matter-of-fact and defiant.

Not for the first time in his career, the editors prevailed. “Reporter,” a 355-page memoir, will be released on Tuesday. The book is by turns rollicking and reflective, sober and score-settling. It reconstructs his reporting on Vietnam, his feuds with Henry Kissinger, the foibles of former bosses like A.M. Rosenthal at The New York Times and William Shawn at The New Yorker. It also exhumes journalism’s flush, predigital heyday — when newspapers felled presidents and Mr. Hersh, as a newbie at The Times, was put up at the Hôtel de Crillon while on assignment in Paris.

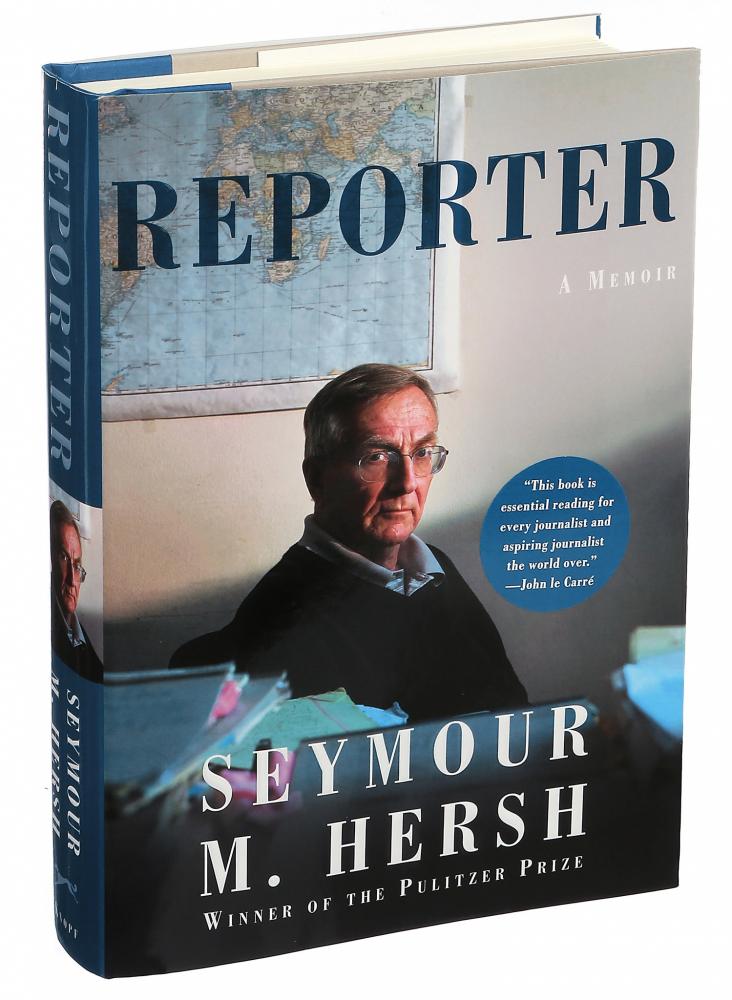

“Reporter: A Memoir” will be released on Tuesday. The 355-page book is by turns rollicking and reflective, sober and score-settling.CreditSonny Figueroa/The New York Times

Sentiment, though, is scarce, befitting the flinty style of Mr. Hersh, who has a knack for cycling through employers and exhausting his editors. (After a messy split with The New Yorker, he no longer has a regular venue for his work.) He knocks reporters for laziness and editors for timidity. He notes that major publications passed on his My Lai exposé, fearful of government denials that American soldiers had murdered dozens of Vietnamese civilians. In the end, Mr. Hersh syndicated the stories himself, and won a Pulitzer Prize for his efforts.

As with any Hersh production, “Reporter” has news. He recalls hearing a tip that Richard Nixon’s wife, Pat, went to the emergency room in 1974, shortly after the Nixons had left the White House, saying her husband had hit her. (Mr. Hersh writes that he made a mistake by not reporting this at the time; the Nixon family denied similar allegations of domestic abuse when they surfaced in years past.) He describes Lyndon Johnson expressing his displeasure over an article by meeting a reporter at his Texas ranch and — there is no pleasant way to put this — defecating on the ground in front of him.

He remembers a night in San Francisco during the 1968 presidential campaign, when he was working as the press secretary for Eugene McCarthy. (Yes, Mr. Hersh, the reporter’s reporter, had a stint on the public-relations side of the game.) Mr. McCarthy had never smoked pot, so Mr. Hersh produced a joint; joining the group was Jerry Brown, the future governor of California. “The stuff did little for McCarthy, so he said, but it did much more for Brown,” Mr. Hersh writes.

A spokesman for Mr. Brown, contacted for this article, called the anecdote “a complete and total fabrication.” Mr. Hersh shrugged off the denial. “omg … why is he making a big deal of it?” Mr. Hersh wrote in an email. “it was the 60s, was it not?”

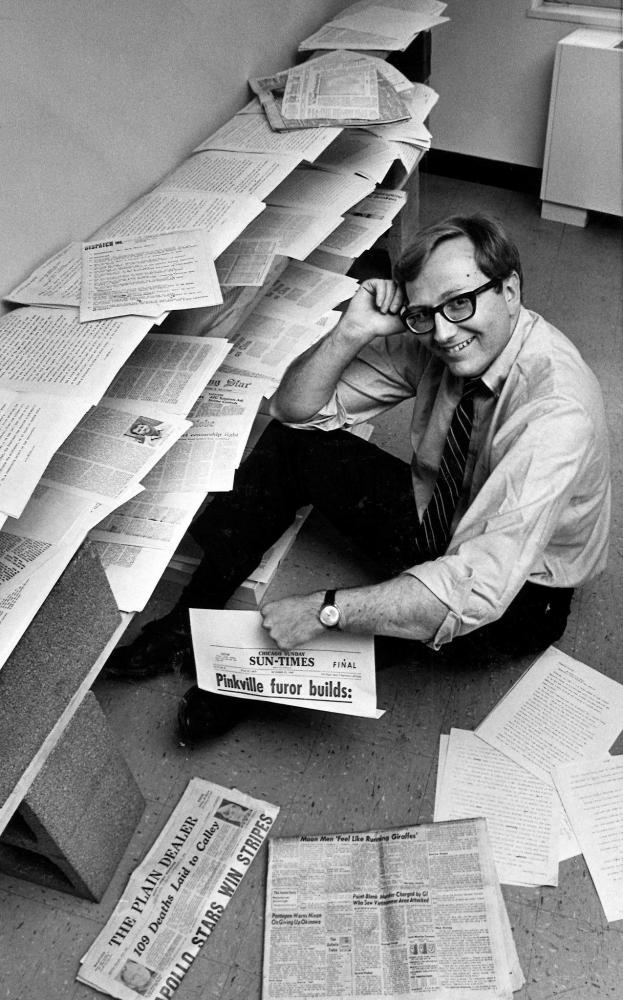

Mr. Hersh in the office of Dispatch News Service in Washington in 1970, after being awarded the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting. He exposed the massacre of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai.Credit: Bob Daugherty/Associated Press

During an interview in his cluttered office here, between the White House and the home he shares with his wife, a psychoanalyst, in the Cleveland Park neighborhood, Mr. Hersh seemed not much different from how Time magazine described him in 1975: “He is in turn talkative, churning, abrupt, zealous, egotistical and abrasively honest.”

In athletic shoes and a V-neck sweater, he bounced from topic to topic. He offered measured support for Gina Haspel, the new director of the C.I.A., and recalled the time he and Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker, watched “Platoon.” (Mr. Ellsberg cried, he said.) A framed photograph of Mr. Kissinger, the subject of one of his books, hangs above his desk; in it, Mr. Kissinger is stuffing his face with cake.

Mr. Hersh’s place in the pantheon of reporters is secure, but his current status is ambiguous. In arguably the most fertile moment for investigative reporting since Watergate, he has been on the sidelines. By choice, he said.

“I’m not going to write anything about the whole last two years,” he said. “The story’s fixed now. ‘Trump bad, Democrats good.’ It’s a fixed story. And, of course, it’s a little more muddled than that. A lot more muddled than that.” He added, “I doubt if I went to The Washington Post or The New York Times with a story, they’d run it. Doesn’t bother me.”

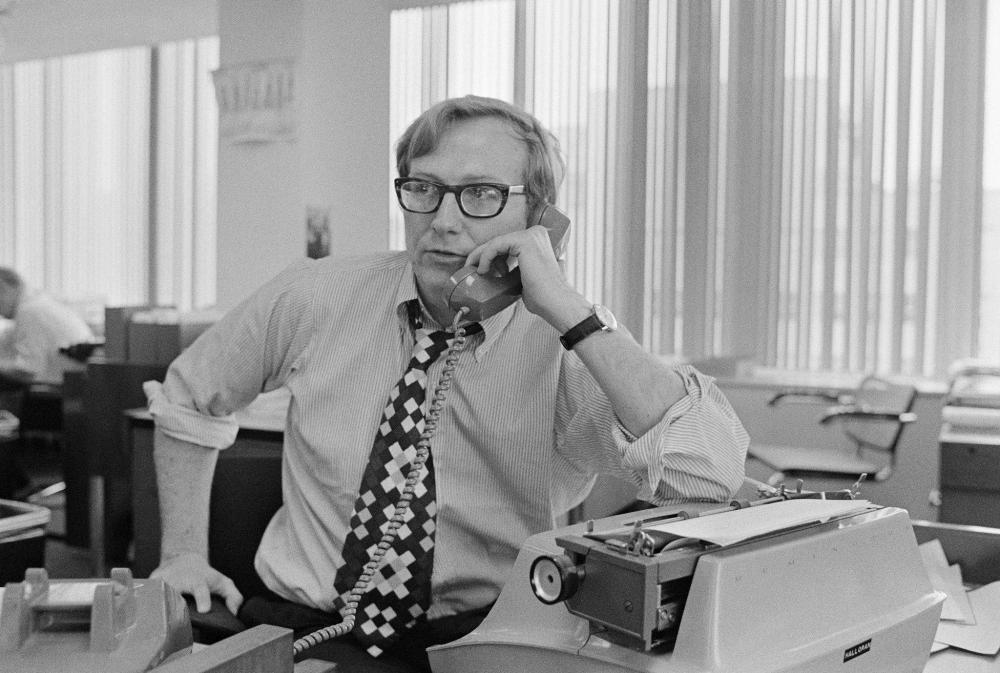

Mr. Hersh at his desk in the Washington bureau of The New York Times in June 1972. Mr. Hersh has a knack for cycling through employers and exhausting his editors.Credit: Wally McNamee/Corbis, via Getty Images

Mr. Hersh has found himself at odds with much of Washington’s reporting establishment since The New Yorker declined to publish his report on the death of Osama Bin Laden — a story that directly contradicted the account given by the Obama White House and much of the mainstream press. Mr. Hersh instead turned to an unlikely venue, the London Review of Books, to make his case that Pakistani intelligence had not only been aware of the Bin Laden mission, but had cooperated with it as well.

Other reporters criticized the article, and his subsequent reporting on Syria, which questioned whether President Bashar al-Assad had gassed his own people, was similarly derided. But Mr. Hersh is unrepentant.

“It’s pretty clear now; nobody disputes it anymore,” he said, in an asked-and-answered tone, when I brought up the Bin Laden piece. (In fact, many reporters and former White House officials still dismiss his version of events as fantasy.) “When I wrote it, there was just hell to pay.” In his memoir, which refers to “the American murder of Osama Bin Laden,” he writes: “I will happily permit history to be the judge of my recent work.”

In the book he also writes that David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, had grown too chummy with President Barack Obama, the subject of Mr. Remnick’s 2010 biography — an assertion the editor, in an interview, called “nonsense.” But Mr. Remnick took a warm tone toward his former star reporter, whose New Yorker scoops included the Abu Ghraib prison abuse story.

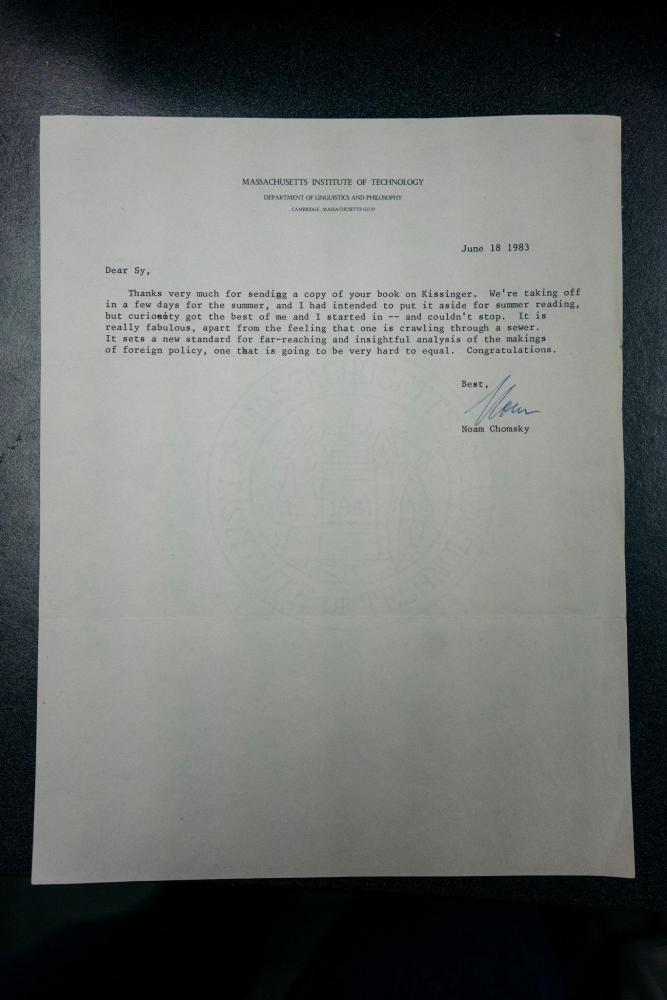

A letter in 1983 from the linguist and critic Noam Chomsky to Mr. Hersh about his then-new book, “The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House.” “It is really fabulous,” Mr. Chomsky wrote, “apart from the feeling that one is crawling through a sewer.”Credit: Lexey Swall for The New York Times

“I think that Sy — and I say this with great respect — psychologically needs to feel that editors are ‘The Man,’ capital T, capital M, and I mean that in a non-gendered way,” Mr. Remnick said. “They are the authority figures who need to be pushed back against, and so I don’t take that personally.”

He added: “When all was said and done, his achievements are enormous.”

In his office, Mr. Hersh fielded a call from his son, a reporter at Vice News, and laid out his “two little rules” rules for reporting: “Read before you write. And, secondly, get the hell out of the way of a story. You don’t say ‘in a startling development,’ you tell the development. You don’t need an adjective in the first two paragraphs. You don’t have to sell it to yourself.”

I was expecting Mr. Hersh to have a lot to say about the Trump presidency, but he often changed the subject. He eventually allowed that the narrative of Russian meddling struck him as incomplete. “Do you have any evidence that these 13 guys really were trolls and changed the election?” he asked, referring to the 13 Russians indicted by the Justice Department in February on charges they tried to subvert the election and support Mr. Trump.

“There have been social science studies of the impact of any particular thing on Facebook, and it’s, like, zippo!” Mr. Hersh went on. “We have a divided America, a really bitterly divided America. Do we really need the Russians to tell us we’re a troubled country?”

Mr. Hersh’s main concern these days is the 24-hour, Twitter-driven news cycle, which he denounces in his memoir as “sodden with fake news, hyped-up and incomplete information.”Credit: Lexey Swall for The New York Times

He called the president an unserious man surrounded by “terrible people.” But he has reported on unscrupulous leaders before. “We will survive Trump,” he said. “America will go on.”

These days, his main concern is the 24-hour, Twitter-driven news cycle, which he denounces in his memoir as “sodden with fake news, hyped-up and incomplete information.” In his office, he brought up unprompted the manifesto of Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber.

“I hate to say it — if he hadn’t killed people, if he hadn’t been a psychotic who thought it was O.K. to mail bombs to people, if you went and reread it, he’s talking about machines taking over our life,” Mr. Hersh said. “We’re all going to be beholden to machines, and here we are, you know: Facebook and Instagram. I mean — it’s happened!”

It was a funny thing to say for a man whose critics accuse him of being a conspiracist and an obsessive — though Mr. Hersh takes those complaints in stride. He has faced skeptics throughout his career: from his junior college days working at his family’s dry cleaning business to a brief stint running a weekly paper in suburban Illinois where Mr. Hersh sold ads and sometimes delivered the papers himself. Later, he carried out a nationwide hunt for William Calley, the soldier whose interview with Mr. Hersh would unlock the grim secrets of My Lai.

“There’s a kind of monomaniacal gene that you have to have, a sense of single-minded pursuit, that Sy at his best exemplified,” Mr. Remnick said. “He never stopped being hungry. The hunger, the sense of skepticism about power, is always characteristic of Sy.”

Mr. Hersh has been going to physical therapy lately to treat a torn rotator cuff. He had ignored a pain in his shoulder so he could keep up his usual tennis game. “I realized when I hit a ball, I couldn’t move my arm,” he said. “And I kept on playing until one day, by mistake, I pulled my arm too high.”

“All I had to do,” he added, “was stop playing. All I had to was stop playing! And everything in me said, ‘Stop playing.’”

Damn the consequences. Mr. Hersh kept playing.

Spread the word