Better Answers on Trade for the U.S. Economy; 4 Charts Showing Why Putting Tariffs on Your Friends Is a Bad Idea

Better Answers on Trade for the U.S. Economy - Stan Sorscher (Talking Union)

4 Charts Showing Why Putting Tariffs on Your Friends Is a Bad Idea - William Hauk (The Conversation)

Better Answers on Trade for the U.S. Economy

by Stan Sorscher

May 28, 2018

Talking Union

In 2016, President Trump prevailed over 17 establishment opponents. He is a disrupter. In particular, he disrupted establishment trade policies that have failed millions of Americans.

Too many workers and communities have been left behind. Too much mistrust has grown regarding the way we’ve managed globalization. Wages have fallen far behind the growth trends of previous generations.

The neoliberal free-market free-trade trickle-down orthodoxy, which we have followed for decades, is exhausted — socially, politically, and economically.

We don’t really understand Trump’s tariffs, or bluster, or impulsive negotiating tactics, but we do understand that we need a change in direction.

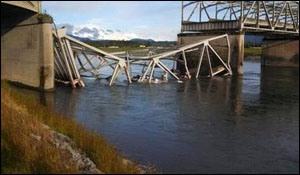

We need new, effective public policies to deal with real problems that affect most people in America — inequality, climate change, health care, opioid addiction, student debt, and decaying infrastructure. We desperately need a manufacturing strategy that creates good new jobs, and stronger employment relationships that would raise family income.

To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, “Unregulated free market orthodoxy cannot solve these problems — free market orthodoxy IS the problem.” Our big policy challenges are all market failures.

David Brooks told us that Donald Trump is the wrong answer to the right questions. Trump’s disruption gives us the opportunity, right now, to find better answers the right questions. We should start by rehabilitating the role of public policy, restoring trust in public institutions and re-legitimizing the role of government in solving our problems.

China understands this. So do Japan, South Korea, Germany, and the Nordic countries. Also, they all recognize their legitimate national interests. They have various forms of mixed economies, including well-designed industrial policies to improve their living standards. We understood this when we industrialized our economy, and we understood it again in the decades after World War II.

China has a national strategy to become the leader in 10 industries of the future. South Korea built a formidable manufacturing economy and raised living standards dramatically. China, Japan, and Europe have modern high-speed rail. China is investing in billions for infrastructure to move goods to their key markets around the world. China targeted solar energy as a key industry of the future, and invested $126 billion there last year.

On the other hand, our economic and trade policies steadily moved our industrial base offshore and we tell ourselves “these jobs won’t come back.” We accept “D+” ratings on our neglected infrastructure, and can’t pass an infrastructure bill. Our approach is ill-suited to the 21st century global economy.

China invests billions in R&D, knowing their investment will be commercialized in their domestic economy. Our billions in publicly funded R&D will be commercialized offshore, producing good jobs in Malaysia, Vietnam, India, China, Mexico, and Ireland.

Foreign students are subsidized to study at U.S. universities. Our own students pay prohibitive tuition costs, taking on debt and risk. Many graduates don’t find a job in their field of study.

We have done better on each of these measures in the past.

Inequality and climate change — the defining problems of our time — are the biggest market failures in human history. Solutions will require new public policies. NAFTA and subsequent trade policies take exactly the wrong approach. They are designed to merge our economy into the global economy, blur national borders, and push aside public interests.

Economic and trade policies should balance investor interests with public interests. That’s what we expect any political system to do. That will be necessary, important, and fundamentally different from the trickle-down economic policies and free-trade NAFTA approach.

President Trump fumbles with this realization. He recognizes the urgency of “doing something.” His tariffs are certainly something, but Trump’s instinct is to tear down social cohesion, hit back at his rivals, fan conflict, and diminish our leadership in the world.

Our first conversation should be about restoring social cohesion, and recognizing that we all do better when we all do better. Our purpose is to raise living standards and improve well-being in our communities. In a mixed economy approach, we would create policy-driven strategies to address inequality, climate change, health care, education, investment in infrastructure, restoring our industrial base, and making key social investments we have let wither for 30 years.

When President Trump says it, it sounds ominous, but every country does expect public policies to express their legitimate national interests. What we don’t hear from President Trump is that the purpose of an economy is to raise living standards. That is true of our domestic economy, and equally important for the global economy. We can recognize legitimate national interests, raising living standards everywhere, without being nationalists or xenophobic.

President Trump has disrupted economic orthodoxy. We no longer expect the invisible hand of free markets to solve serious social, environmental, and economic problems. But, Donald Trump is transactional; he lacks a coherent vision. His answers look suspiciously beneficial for global corporations, the financial industry, and very wealthy donors.

We have campaign seasons in 2018 and 2020 to consider different answers to Trump’s questions. Where should we be investing in people, infrastructure, innovation, industries, communities, and clean energy? In each case, we should ask, “Who gets the gains from productivity, innovation, investments, and globalization?”

President Trump has put those questions into play. We haven’t had this good an opportunity for years.

[Stan Sorscher is a labor representative for the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA), IFPTE 2001.]

4 Charts Showing Why Putting Tariffs on Your Friends Is a Bad Idea

By William Hauk

June 6, 2018

The Conversation

Europeans, Canadians and Mexicans buy more American goods and services than anyone else in the world. So why would the Trump administration be willing to start a trade war with the United States’ most important trading partners – as well as some of its oldest allies?

The current dispute started back in March, when the White House proposed tariffs on all imports of steel and aluminum on national security grounds. That led to threats of retaliation. The administration granted temporary exemptions to several key allies, including Canada, Mexico and the European Union. As of May 31, they’ve all expired, and the U.S. government decided not to renew them.

Now the EU, Mexico and Canada are beginning to make good on those threats.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the tariffs “totally unacceptable” and “an affront” to Canadian soldiers who have served alongside Americans in numerous conflicts.

As an economist who studies international trade, I thought it’d be instructive to explore the trade relationships the U.S. has with each partner to show just how important they are – and what would be the consequences of a full-blown trade war.

Why they’re upset

The Trump administration placed a 25 percent tariff on steel and 10 percent tariff on aluminum with the aim of propping up U.S. metals manufacturers.

A tariff is basically a tax on imports that raises the price of foreign company’s products for American consumers, putting imports at a disadvantage to domestic producers.

To see why these three U.S. allies are so upset, one need only look at the biggest suppliers of U.S. metals. Canada dominates, supplying more than a quarter of all U.S. steel, aluminum and iron imports in 2016. More importantly, steel exports to the U.S. make up more than half of total Canadian production.

The EU came second at 14 percent, while Mexico ranked fifth with 5.4 percent of U.S. imports. Steel exports to the U.S. also make up more than half of Mexican production.

America’s biggest customers

The EU is the single biggest market for exported U.S. goods, buying US$270 billion of American products in 2016, followed closely by Canada and Mexico. By comparison, China buys just $116 billion.

On the flip side, Americans purchase more from those countries than they sell, creating bilateral trade deficits that the president hates – even as most economists say they don’t matter. The U.S. imports $417 billion in goods from the EU, $294 billion from Mexico and $278 billion from Canada.

When the steel tariffs were first proposed in March, the EU, Canada and Mexico all reacted by threatening to retaliate with their own sanctions against some of these products.

So far, only Canada and Mexico have done so. Canada announced dollar-for-dollar tariffs on steel and aluminum, as well as sanctions of 15 percent to 25 percent on whiskey, orange juice and other food products. Mexico also slapped tariffs on U.S. steel, as well as various farm products, including pork, cheese, apples, whiskey, cranberries, grapes and canned goods.

While tariffs on these products won’t have much of an impact on the overall U.S. economy, they could be especially painful for particular industries or regions. For example, Mexico is the second-largest consumer of U.S. pig meat, making the industry vulnerable to Mexican tariffs.

And tariffs like those on Kentucky bourbon and motorcycles seem intended to hit key members of Congress where they live – namely, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, the home of Harley-Davidson.

Disruption to U.S.–Canada trade could also affect cross-border supply chains that have grown during the NAFTA era. The automotive industry is particularly vulnerable in this regard.

Although the EU hasn’t pulled the trigger on its own tariffs – yet – it recently opened a case at the World Trade Organization, arguing Trump’s tariffs can’t be justified on national security grounds and are no more than “pure protectionism.” A negative judgment at the WTO could result in the U.S. having to compensate aggrieved foreign producers or face broader retaliatory measures.

American consumers will also feel pain

While the purpose of Trump’s tariffs is to shift U.S. steel consumption away from foreign producers and towards domestic producers, Americans will share some of the pain as well.

For example, if automakers have to pay more for the steel used in cars, you’ll see that effect when you visit your local dealer. One estimate put it at an additional $175 per vehicle.

And higher prices for things that require steel or aluminum like cars, planes, construction and appliances can slow the rest of the economy. When President Bush tried a similar tariff in 2001, it was estimated that it cost American consumers $400,000 for each domestic steel job saved.

The reaction of the EU, Canada and Mexico raises the possibility the U.S. is facing down a full-blown trade war – even as it does the same with China. Whether tensions can be turned down before serious harm is done remains to be seen.

[William Hauk is Associate Professor of Economics at the Darla Moore School of Business at the University of South Carolina, where he teaches international trade and intermediate macroeconomics. He does research on issues related to international trade, political economy, and economic growth.]

Spread the word