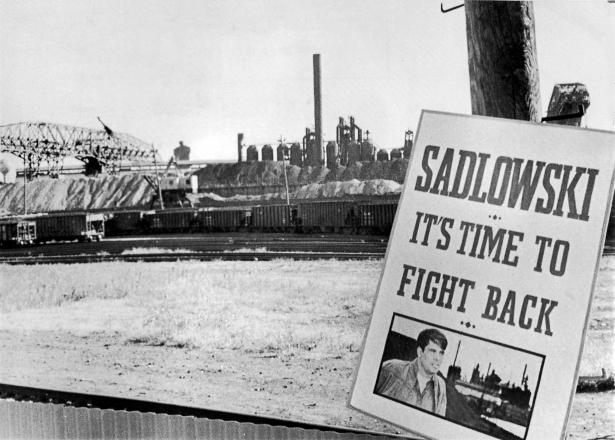

The late 60s and 70s gave rise to grassroots movements for union democracy all over the United States. The ones in the UAW and UMW have been written about the most but the Fight Back in Steel was no less momentous.

The one name that stands out in this national uprising is Edward Sadlowski, the leader of the Fight Back in Steel who rose from an oiler’s job to District Director of the largest District in steel, at that time, known as District 31. He went on to challenge the top bureaucracy running for president in 1976. On June 10, 2018 “Oil-Can Eddie,” as he was known, died. For those of us who worked with him or knew him, we pay tribute to his endless contributions to democratic unionism. There could not be a greater loss with his passing to grass-roots democracy in the union movement.

Ed Sadlowski hired into a steel mill in 1956, at US Steel South Works on the south side of Chicago. His father had been a steelworker and active in the CIO organizing campaigns. He had been a member of USWA local 1010, known as the “red local.”

Eddie was not only an activist, organizer and leader, but also a labor historian. My first long conversation with Eddie happened at the USW training center at Linden Hall outside Pittsburgh in the ‘80s. I was there teaching in a leadership program and mentioned that I was about to explore the mill towns along the Monangahela. He said “let me be your guide.” Eddie had a wealth of stories about the workers’ and the union’s history. I doubt if anyone knew more than Eddie.

There had been earlier struggles for a more democratic union in steel; especially important was the black struggle for equality that culminated in the Ad Hoc Committee of Black Steelworkers in the 1960s.

The USWA was formed during the battles of the 1930’s for industrial unionism, but its structure was set up along the lines of the UMW because it was the mine workers that provided financing and leadership for the unionization drives in steel. The USWA was very centralized and very top down. Plus, the union came of age during the period of cold war anti-communism. Many of the radicals that built the union were marginalized and, especially in District 31, the Directors were staunch anti-communists and branded every radical as a red. In fact, they relied on the FBI for reports on FightBack meetings to label any worker fighting for a voice as a red.

But it is Eddie’s own story that we must celebrate and commemorate because he brought the union out of its conservative past to challenge the politics that had left the union defenseless against downsizing, automation, restructuring and globalization. After the dramatic 1959 strike in steel, the Union had bound itself with a No-Strike Agreement, known as the ENA (Experimental Negotiating Agreement). In addition, the Executive Board of District Directors controlled everything. They dominated every convention and it was at the convention that officers were elected. There was no direct election of officers. It had become a white male dynasty, wedded to collaboration and compromise.

Younger steelworkers throughout the country were opposed to the no-strike agreement, and were demanding nationwide election of officers, each member one vote. What Eddie did was forge many caucuses and local movements into a national powerhouse that was inclusive, women as well as men, black and Latino as well as white. Eddie’s slate when he ran for president of the union was the most diverse group ever to run for office in steel.

Ed Sadlowski lost that bid because the “official family” had worked very hard to make sure he could not prevail. He won the majority of the votes in the U.S.-based locals but lost the Canadian ones where he had been limited in his access to locals.

The Fight Back was able to end the convention election of officers and the ENA. The leadership in locals across the country changed hands and radicals assumed office. The Fight Back was not able to survive its link to the Sadlowski campaign, but many new activists took office and transformed local politics.

Eddie’s path included many “wins,” starting with his taking the presidency of his own Local 65 in 1964 when he was only 26. Other locals followed suit; the first woman president of a basic steel local won also, Alice Puerala. The rank-and-file caucus at USWA Local 1010 won as well. For the first time a strong women’s caucus was formed, the District 31 Women’s Caucus. Its president was Ola Kennedy, an activist from the Ad Hoc Committee of Black Steelworkers, and the vice president was Roberta Wood, a strong left activist.

Ed Sadlowski never retired even after he retired from steel. He continued union organizing and representation, worked with AFSCME and other unions. Eddie always made himself available to anyone who wanted to talk, get advice, meet with him, or learn from him. “Oil-Can Eddie” had mythical stature. Eddie Sadlowski was one of the best unionists the labor movement ever had.

Ruth Needleman, NWI Resist, Professor Emerita Indiana University, author of Black Freedom Fighters in Steel: The Struggle for Union Democracy

Spread the word