Reporters and political commentators often express frustrated surprise at the steadfast support of President Trump from most Republicans in the House and Senate. But they shouldn’t — it has happened before.

In fact, when these critics refer back to the Watergate era as a time of bipartisan commitment to the rule of law over politics, they get it exactly wrong. Defending the president at all costs, blaming investigators and demonizing journalists was all part of the Republican playbook during the political crisis leading up to the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

Despite the fact that 32 people and three companies have been indicted so far by the special counsel, Robert Mueller, only four of 11 Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee joined Senate Democrats earlier this year in an effort to protect Mr. Mueller’s investigation. The House majority leader, Kevin McCarthy of California, said in June that he thinks “the Mueller investigation has got to stop.” Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky and the House Intelligence Committee chairman, Devin Nunes of California, have joined Mr. Trump in calling the investigation a “witch hunt.”

Dispiriting, perhaps, but not shocking or unprecedented. In late 1972, when a Democratic congressman, Wright Patman of Texas, began to investigate connections between Mr. Nixon’s aides and the Watergate burglary, the House Republican leader, Gerald Ford of Michigan (who later succeeded Mr. Nixon as president), called it a “political witch hunt,” according to the historian Stanley I. Kutler in his book “The Wars of Watergate.”

Mr. Ford wasn’t alone, and the countercharges didn’t end even as the evidence piled up. After reporters revealed close ties between the Watergate burglars and Mr. Nixon’s administration and re-election campaign, Senator Robert Dole of Kansas jumped to the president’s defense. He labeled the media accounts “a barrage of unfounded and unsubstantiated allegations by George McGovern” — whom Mr. Nixon defeated in the 1972 election — “and his partner in mud-slinging, The Washington Post.”

There is a big difference, of course, between the Watergate era and now. Republicans now control both houses of Congress; in the 1970s the Democrats held the reins.

In early 1973 Senate Democrats led the charge to form a special committee to focus on Watergate. While the Senate Watergate Committee was being created, Republican Senator Edward Gurney of Florida belittled the investigation as “one of those political wing-dings that happen every political year.” Ted Stevens, a Republican senator from Alaska, repeated Mr. Ford’s warning that the investigation could become a “political witch hunt,” according to Mr. Kutler.

Meanwhile, the ranking Republican on the Senate Watergate Committee, Howard Baker of Tennessee — a man often lauded for putting principle over party — met with Mr. Nixon to discuss strategy. To “maintain his purity in the Senate,” Mr. Baker didn’t want anyone to know about meeting Mr. Nixon, wrote the White House counsel, John Dean, in a memo before a meeting with Mr. Nixon. Once the hearings started in late spring of 1973, Mr. Baker’s staff leaked information about the committee’s witnesses and plans to Mr. Nixon.

When Mr. Baker famously asked, “What did the president know, and when did he know it?” during the Watergate hearings, he meant to protect Mr. Nixon in the mistaken belief that the president didn’t know about the Watergate cover-up until many months after it occurred. The question backfired once evidence mounted that Mr. Nixon was involved in the cover-up from the start, and Mr. Baker eventually became a critic of the president.

After it was revealed in July 1973 that Mr. Nixon had secretly taped conversations, Mr. Ford said he found nothing wrong with the president’s practices. Republican Senator John Tower of Texas later warned Congress not to get caught up in “the hysteria of Watergate.”

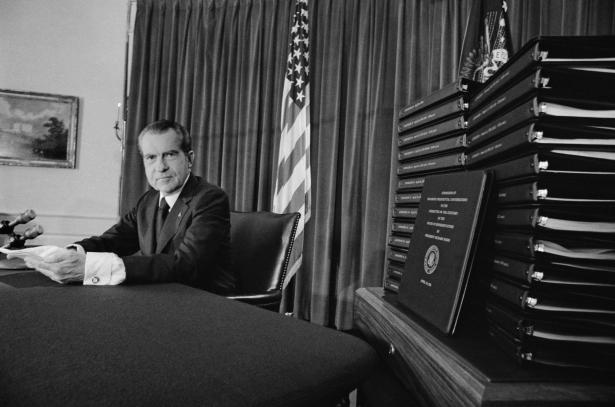

Most congressional Republicans rallied around Mr. Nixon when the White House released edited transcripts of those tapes in April 1974 that showed Mr. Nixon scheming with his aides. As the House Judiciary Committee began debating possible impeachment in July, Representative Delbert Latta of Ohio said the evidence failed to prove Mr. Nixon’s direct involvement in Watergate.

Mr. Latta and most other Republicans on the Judiciary Committee voted against all articles of impeachment on July 27-30, 1974. Eleven of 17 Republicans voted against the obstruction-of-justice article, 10 of 17 opposed the abuse-of-power resolution, and 15 of 17 voted against the article based on the president’s refusal to produce tapes in response to the committee’s subpoenas.

More Republicans abandoned Mr. Nixon on the obstruction-of-justice charge only after he complied with the Supreme Court’s order on Aug. 5, releasing the “smoking gun” tapes that proved he had ordered a cover-up of the Watergate crimes. Still, many party members of the Judiciary Committee later filed reports arguing that Mr. Nixon was innocent of two of the three articles of impeachment sent to the full House.

By then it was clear, however, that Mr. Nixon did not have the votes to save his presidency. The Senate Republican leader, Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania, and two prominent Arizona Republicans — Senator Barry Goldwater and the House minority leader, John Rhodes — visited Mr. Nixon on Aug. 7 and told him he could no longer avoid impeachment in the House and conviction in the Senate. The president announced his resignation the next evening.

During Watergate, most Republicans in Congress supported Mr. Nixon until the tapes provided undeniable evidence that he had obstructed justice. It remains to be seen whether current party leaders will support Mr. Trump no matter what evidence Mr. Mueller’s investigation unearths about the conduct of the president and his aides. Such behavior might be unwarranted, but it won’t be unprecedented.

Michael Conway served as counsel for the House Judiciary Committee during its impeachment inquiry of President Richard Nixon. Jon Marshall is an assistant professor at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University and the author of “Watergate’s Legacy and the Press: The Investigative Impulse.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion), and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter.

Spread the word