More than 2,200 Americans have been killed in the Afghan conflict, and the United States has spent more than $840 billion fighting the Taliban insurgency and paying for relief and reconstruction. The war has become more expensive, in current dollars, than the Marshall Plan, which helped to rebuild Europe after World War II. That investment has created intense pressure for Americans to show the Taliban are losing and the country is improving.

But since 2017, the Taliban have held more Afghan territory than at any time since the American invasion. In just one week last month, the insurgents killed 200 Afghan police officers and soldiers, overrunning two major Afghan bases and the city of Ghazni.

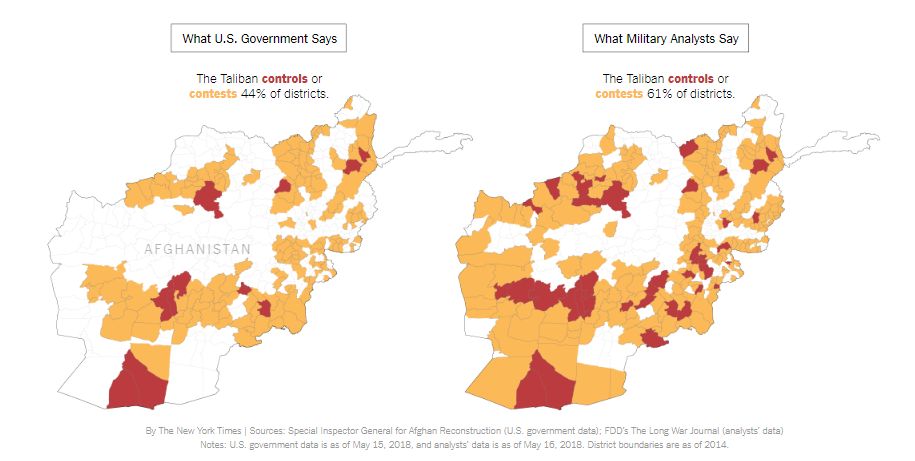

The American military says the Afghan government effectively “controls or influences” 56 percent of the country. But that assessment relies on statistical sleight of hand. In many districts, the Afghan government controls only the district headquarters and military barracks, while the Taliban control the rest.

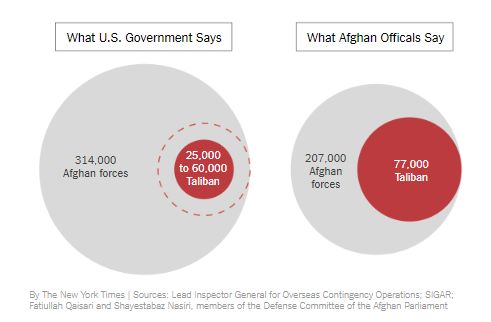

On paper, Afghan security forces outnumber the Taliban by 10 to 1, or even more. But some Afghan officials estimate that a third of their soldiers and police officers are “ghosts” who have left or deserted without being removed from payrolls. Many others are poorly trained and unqualified.

The Afghan government says it killed 13,600 insurgents and arrested 2,000 more last year — nearly half the estimated 25,000 to 35,000 Taliban fighters an official United States report said were active in the country in 2017. But in January, United States officials said insurgents numbered at least 60,000, and Afghan officials recently estimated the Taliban’s strength at more than 77,000.

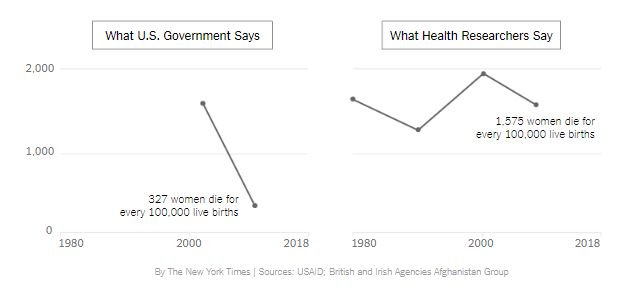

With the status of the battlefield looking grim, American officials say that at least the coalition has improved Afghan living standards — although often they use exaggerated claims there, too.

The most blatant example may be maternal mortality, one of the most important indicators of a society’s health. In 2002, American officials reported that 1,600 Afghan mothers died for every 100,000 live births, a rate comparable to Europe during the Middle Ages. By 2010, the United States Agency for International Development said the rate had improved drastically, falling to 327.

Researchers noted that not since the world discovered antibiotics has any nation seen such a big improvement in maternal health. The long-running security and development challenges Afghanistan faces are factored into health researchers’ estimates of maternal mortality. The British and Irish Agencies Afghanistan Group cited a study indicating that 1,575 women died out of 100,000 births in 2010. Other estimates cited by the group put the figure at 885 to 1,600 of 100,000 — meaning that nearly one in a hundred Afghan women will die giving birth. The rate in the United States is 24 in 100,000.

USAID points to a similarly drastic improvement in life expectancy, to 63 years in 2010, up from 41 years in 2002. But the figures were adjusted to ignore a high death rate in early childhood, which skewed results.

The World Health Organization, meanwhile, estimated in 2009 that Afghan life expectancy was 48 years. Even the C.I.A. does not agree with USAID’s number, estimating in 2017 that Afghans typically live to age 51.

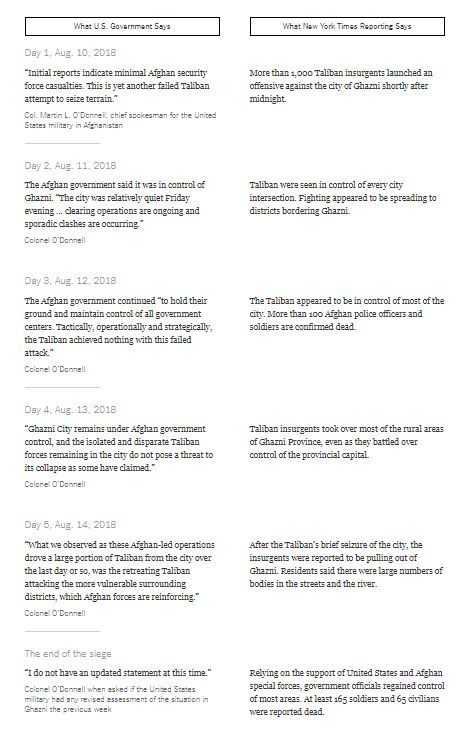

The strategic city of Ghazni in southeastern Afghanistan was overrun last month by the Taliban, who took everything but a few government facilities. The local authorities denied there was any problem, telling President Ashraf Ghani only late on the third day how serious it was, officials said. They did regain control from the insurgents, but only after six days, and at the cost of nearly 200 police officers and soldiers killed. Throughout, the American military led the chorus of denial.

Rod Nordland and Fahim Abed reported from Kabul, and Ash Ngu from New York.

Correction: Sept. 13, 2018

A map with an earlier version of this article incorrectly showed more districts as contested than military analysts had said. The district percentages that appeared with the map were correct.

Spread the word