In 1970 there was a nationwide strike of postal workers, and I became involved in this event, both as an ordinary postal worker and as an officer in a postal union. I eventually wrote a novel about it called Waiting for the Earthquake, which was published by Atlantic-Little, Brown.

The strike arrived at a time of great tension—and great change—in America. In 1964 and 1965, the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts were voted into law, constituting perhaps the most important America political turning-points of the 20th century. But the late 1960s and early 1970s were a very painful and unpredictable time, as the Vietnam War divided the country and deadly riots broke out in many African-American neighborhoods.

Still, for a great many middle class and working families, things weren’t so bad. Despite the growing pall of a brutal war in Asia, jobs were plentiful and wages mainly okay.

With at least one notable exception.

The federal government had discovered that they could systematically repress salaries of postal workers, as well as all workers in the public sector, as a hedge against “stagflation,” a stagnant economy plus rampant inflation. Federal policy-makers especially focused on postal workers, since the Post Office was the second-largest employer in the land, and postal workers had to go to Congress for pay raises. Therefore, putting a lid on postal wages was relatively easy, since all Congress had to do was ignore any request by a postal union.

The postal unions were not allowed to engage in collective bargaining at that time, so postal workers were reduced to begging, hat in hand, to whomever in Congress they could get to listen to their tale of woe. Since the federal government had been holding down wages for three decades, postal workers were simply not making enough money to make ends meet (a little more than two dollars an hour, as I remember.)

I already had a couple of children when I came to work at the Post Office, even though I was in my early twenties. I ran for office in Local 2 of the United Federation of Postal Clerks in San Francisco, and ended up as Vice-President. I also became a delegate to the San Francisco Labor Council for the next several years.

Just as so often happens among today’s fast food workers, a great many postal workers and their families discovered that they had “too much month and not enough paycheck.” If you couldn’t make the paycheck last to the end of the month, and welfare and food stamps weren’t enough, you had to borrow money. Some postal workers I knew were borrowing money on a monthly basis, gradually finding themselves pulled into a terrifying system not unlike that old song about “owing your soul to the company store.” They’d try to stop borrowing, but when the next emergency came along (or the next child) they’d have to borrow more.

The mood of the country gradually turned ugly. A traumatized nation had witnessed the tragic assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, and hopes for peaceful reform of the nation seemed to perish with them. Moe Biller, a well-known and greatly beloved postal clerks’ leader in New York, angrily denounced postal facilities in the large cities as “dungeons,” dirty, often dangerous, sweltering in summer and freezing in winter. Rincon Annex, where I worked, featured beautiful WPA-type murals in the lobby, which have thankfully been saved as iconic examples of social-realism—but in the 1960s and 1970s there was nothing artistic about the working areas, which featured surrealistic fluorescent lights and the constant roar of mail-sorting machines.

For reasons unknown, a decision was made in postal management to paint the interior walls of Rincon Annex pink, since they believed that the color pink had a calming effect on the workforce. It was as though management sensed that something disruptive and possibly dangerous was afoot, but didn’t know what it was and had no idea what to do about it. Over a period of time I became aware that some desperate postal workers, mainly on the east coast, were covertly—and very quietly—discussing the possibility of a wildcat strike in New York City and New Jersey.

Furthermore, although it wasn’t widely reported, there had been a quiet but significant “sickout” of letter carriers in one of the mail processing units of New York City in 1969, which management went to great lengths to cover up. The impoverishment of the average postal workers had already become a major subject of op-ed writers and cartoonists in daily journalism, so the public was starting to get the idea that something was up.

But what were postal workers to do? Strikers against the government could be punished with up to five years in prison, so I thought at first that strike talk might just be trash talk born of economic desperation. Yet something had to give—the status quo wasn’t working, and people were getting desperate. I went out of my way to seek advice from people who had been in union politics for a long time.

One guy that I found particularly inspiring was the late Dow Wilson, President of Local 4 of the Painters’ Union. Sadly, Dow was assassinated by a mafia gunman right across the street from where I used to attend Labor Council meetings in the Mission District. But he was a heroic figure, with balls of brass, a sense of humor, and didn’t take himself too seriously

One group I met with regularly were some people on the left who were mainly academics, but with one experienced trade unionist from the printing trades. I also met with people who were active in Locals Six and Ten of the Longshoremen and Warehousemen, mostly ex-Communists but still on the Left politically. During the middle 1960s I was lucky enough to meet with the late, great Charles “Chili” Duarte, ILWU President of Local Six. He was interested in the situation of the Postal Workers and suggested that I form a Shop Stewards’ Council.

“I don’t know, Chili,” I said. “we have Shop Stewards, but everybody is scared of management in the Post Office. Only one guy wears a Shop Stewart badge, and he’s a total sell-out.”

“Good,” Duarte said. “That way your management won’t expect much opposition from the Shop Stewards. They’ll be sitting ducks when you’re ready to make any kind of strong move.”

Chili recounted the story about Harry Bridges’ early years on the waterfront, how he inherited a sellout union run by leaders who were terrified to throw down with a boss. But Bridges organized quietly from within, without a lot of fanfare, and when the 1934 strike was called he had a base of support that put him in the drivers’ seat. All his power came from that original crew, Chili said.

“Management didn’t know what hit them, because they were expecting Bridge’s union to punk out. Of course, there were a lot of special circumstances in that 1934 strike, including two violent deaths, but it was Bridge’s strong rank and file support that really turned the tide. And management didn’t see it coming.”

I was privileged to sit in on a few Shop Steward Meetings in Duarte’s union. Members were highly educated on how to file grievances, and the arguments to make with line foremen, if and when such arguments were needed. “Teach your members basic trade unionism. Postal workers really need to be exposed to industrial-style unions, because the conditions that postal workers work under are more like factories than public-employee unions.”

I asked Duarte to summarize basic trade unionism. “Easy,” I remember him saying. “First, in negotiation you’re always wanting more money, and better conditions. Then whatever you can get you reduce to a contract that can be enforced in court. The shop steward system polices the contract, and documents the violations. Such a contract should be in force for a discrete amount of time—preferably one, two or three years. As the contract begins to run out, you prepare to get back into negotiations.”

“If management shows signs of breaking out of this basic scenario, tell your members to prepare to strike, even if—or especially if—you are a public-employee union. Get a strike vote if you can. That doesn’t mean you’re really going to strike, but if you can get your membership to vote for it, it shows management to what lengths you are willing to go to get a good contract. A strike vote puts management on notice, and it prepares the members psychologically for the struggle ahead.”

I’ve never heard a better summary of trade unionism than Duarte’s.

It wasn’t long before something finally happened, as it always does, to break the proverbial camel’s back. Postal workers desperately needed a big raise—or a series of raises—to catch up with other workers. But it was at just that point that Congress voted to give postal workers a mere 4 percent raise. And then—wait for it—they voted to give themselves a whopping 41 percent pay raise!

Postal workers were furious. How could Congress be so blind? Tension on the workroom floor spiked.

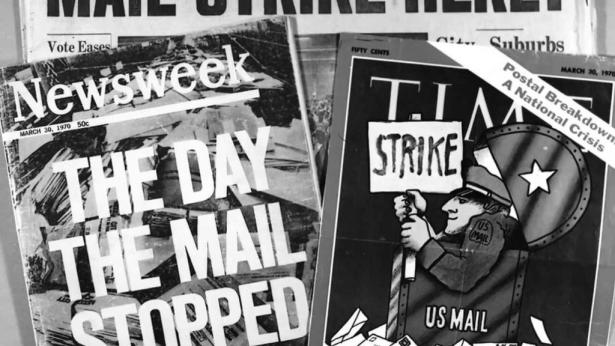

Members of New York City’s National Association of Letter Carriers, Branch 36, met in Manhattan on March 16, 1970, and voted to strike. At midnight the next evening, March 17, picketing began at the main postal facilities. Moe Biller, then a rank-and-file postal clerk leader in the Manhattan-Bronx area (and later the President of the American Postal Workers’ Union) brought postal clerks into the strike, closing down the big mail-distribution centers. Postal unions in New Jersey also voted to strike, as well as a few other urban locals on the east coast. The strike by angry clerks and letter carriers (the latter led by Vincent Sombrotto) was enough to stop all movement of the mail in New York—and New York was, by any standard, the main postal distribution center in America.

And then something truly amazing began to happen. The strike fever began to roll west, across the Middle West and then on to the large cities on the West Coast. Postal workers across the country began to engage in various kinds of strike activity, sometimes picketing openly, and sometimes not. Sometimes people only stayed home for a day or two, or—in imitation of the ‘blue flu’ tactic used by striking police patrolmen—they started calling in sick. Many called in to say they were afraid to come to work because of the large crowds of striking postal workers milling around outside, and disruption inside the facility. Others simply stayed home without calling in.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, I was the only postal union officer (VP of Local 2, United Federation of Postal Clerks), and the only delegate to the Labor Council to openly support strike action. I fully expected to be arrested by the Postal Inspectors or the FBI, and probably indicted by a grand jury. But I’d long ago decided that it was worth it. Postal workers were second only to the auto industry in terms of their numbers, but auto workers made five or six times as much money.

Beginning on the second day, postal workers all over the Bay Area started staying home from work, and people got very creative. We had a big rank-and-file meeting at a church, where I asked for picketers to go with me to the San Francisco Labor Council, which—it so happened—was meeting that night. I was a regular member of the Labor Council, so people knew who I was—but I showed up with about 30 to 40 postal workers which really got the attention of the members, especially the leaders. (This tactic was not new, I hasten to add—as mentioned before, it was a favorite ploy of the late Dow Wilson, President of the Painters Union Local 4, who always took a large rank-and-file contingent with him when he wanted the Labor Council hierarchy to discuss some important issue.)

I asked to be recognized under ‘New Business’ at the Labor Council, and made a motion to support striking postal workers. George Johns, at that time Secretary of the San Francisco Labor Council, hemmed and hawed a great deal, then made a bizarre little speech about the hard work done by postal workers. That was all he could say under the circumstances, really—he couldn’t support the strike outright, since it was against the government, and therefore completely illegal; but it all got onto the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle the next day, and familiarized people with our issues. It also made postal management realize that they were dealing with desperate people who simply couldn’t continue to live on starvation wages.

Some of the strikers fanned out and went to smaller postal facilities, encouraging workers to leave early and stay home. Some postal workers at a facility near the airport walked out together. About this time something very interesting began to happen nationally. The top leaders of the postal unions all piously disavowed the strike, but were at the same time being frantically petitioned by people in the Nixon administration—people who’d previously been unwilling to even acknowledge our existence—to sit down and help postal management negotiate a way out of the prevailing chaos! So, the top leadership did what elected union leaders are supposed to do—they entered into negotiations for a settlement.

It had now become clear to everyone involved that there would have to be very substantial raises for postal workers, because we were all playing catchup ball because of the decades that America had neglected its postal workers.

During the height of the excitement at the postal facilities in San Francisco, the Postal Inspectors infiltrated one of their people into our activities, representing himself as an ordinary postal worker from another area who just wanted to see how strikes were conducted. We found out very early that he was actually a Postal Inspector from the San Francisco office—you can’t keep that kind of thing secret very long in a place like San Francisco—and it then became my responsibility to keep him from harm, as strikers and their supporters were likely also to become aware of his true identity. (It was my belief that if there were mass arrests, he would be used as an expert witness to testify against us. At my request, the young man in question left the area.) On other hand, the Postal Inspectors were always quite fair to me. The FBI, not so much.

Meanwhile the top leadership of the postal unions were engaged in negotiating with postal management and Nixon’s lawyers. They rather quickly reached an agreement, which suggests, first, that the spontaneous nature of the strike in New York had scared the hell out of everybody; and secondly, both sides had been thinking for some time about what they wanted. It had occurred to the Nixon administration that there were far too many postal workers—reportedly at least 250,000—that had participated in strike activity, to indict them all. Such an expedient would have swamped the grand jury system, among other things.

Conclusion

The postal strike of 1970 lasted only a couple of weeks on the East Coast, and was basically over after a week on the West Coast. The purpose was to demonstrate conclusively that postal workers could be pushed only so far, and that the nation could not function if mail was not delivered. It could be described as an unsanctioned or wildcat strike, and it was also a felony-level crime. To get the full measure of this, please remember that any kind of strike against the Post Office at that time violated several different kinds of federal laws. The fact that so many postal workers risked imprisonment was a warning to the Nixon administration, the postal management, and everybody else, that the situation of postal workers had become intolerable.

An unsanctioned or wildcat strike can mean a strike in which the local votes for a job action against the wishes of its national organization. (Like Branch 36 of the Letter Carriers voted to do in New York. The national leadership reportedly never saw that vote coming.) It can also mean a strike that is not approved by the local Labor Council, or not voted on by the membership. All these things could qualify such strikes as unsanctioned strikes, but we should remember that branch 36 of the Letter Carriers in New Work formally held a strike vote, and voted to strike. Later Moe Biller’s Manhattan-Bronx Postal Union voted by secret ballet—rather than a voice vote—to strike, and soon joined the letter carriers on the picket line.

By these standards, the postal strike in San Francisco was 100 percent wildcat. Years later, while casing mail at Rincon Annex, I took to wearing a button on my work apron that said Remember the Wildcat—I Was on the Line. The 1970 strike was a wildcat strike, but it did what every successful strike must do—it produced a written settlement that could be enforced in court. The settlement came in the form of the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, which was signed by representatives of both unions and management, and then became legislation passed by Congress. It wasn’t perfect, but it was fundamentally good for postal workers and patrons.

I was offered a nice advance for my novel Waiting for the Earthquake, and on the advice of my editor, Billy Abrahams, I quit my job to become a writer. Since that time, I’ve written seven published books, although I’ve had occasion many times to reconsider leaving the Postal Service. Last spring, I joined the Democratic Socialists of America, and continue to support them and their publications.

Unfortunately, the Republicans have a desperate plan to privatize the Post Office, a plan that they discuss mainly among themselves, and with their big donors. That is tragic and unjust, because the Postal Service has served the American people well for over 200 years as a public institution. And although the Republicans like to claim that the Post Office loses billions of dollars a year, the truth is that it receives no money from the government whatsoever, having been self-supporting since 1970. Sadly, however, the Republicans will do and say almost anything to privatize the US Postal Service, in order to transform it into a cash cow for themselves and their corporate sponsors. The Republicans and their billionaire supporters are playing hardball because hundreds of billions of dollars are at stake, and they want to control the action.

I am writing a follow-up article about the specific ways in which the billionaires are trying to privatize the Post Office, and how postal patrons and unions can work together to stop them.

Spread the word