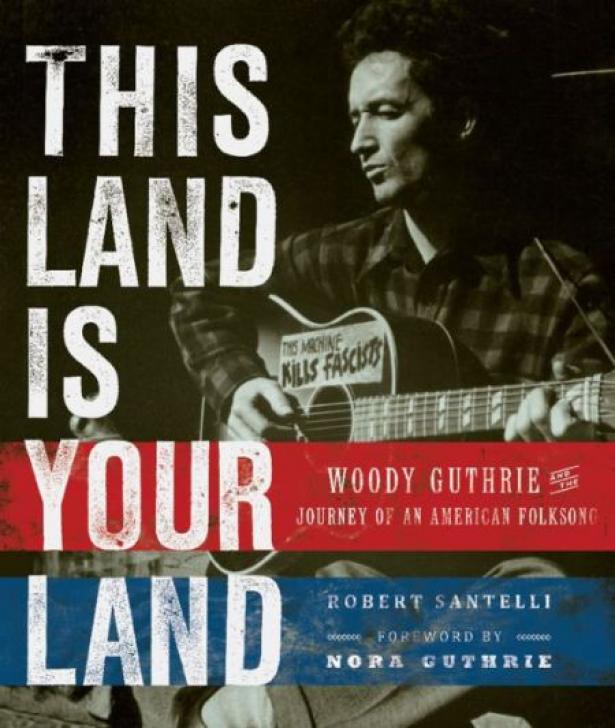

books This Land Is Your Land - Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folksong

This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folksong

Robert Santelli

Running Press

ISBN-13: 9780762445080

At the Arts Theatre in London last spring, a quartet of actor-musicians took a final bow with a reprise of “This Land Is Your Land”, closing Woody Sez, a celebration of the short life and long shadow of Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, born in Okemah, Oklahoma, on Bastille Day 1912 and named after the Democrat who became president of the United States the following year. From kindergarten kids to sprightly octogenarians who had marched behind scores of banners, the audience knew all the words. Clearly the songs of the man we know as Woody Guthrie are in our collective memory: the Oklahoma hills, the Dust Bowl, the Columbia River, the redwood forests, New York Island – all have a resonance, even to those who have never set foot in America.

Robert Santelli first heard Guthrie’s name in “Song to Woody”, on Bob Dylan’s 1962 debut album. Rummaging around Greenwich Village and finding some old Guthrie records, he realised he already knew at least one of his songs. His elementary school teacher had taught the class “This Land”, though “she never mentioned who wrote it, only that it was ‘a good singalong-song’ and ‘about America’”.

Which is how we Brits came to know it when the folk revival spread across the Atlantic in the early 1960s. (Lonnie Donegan had had a hit in the 1950s with “Grand Coulee Dam”, one of Guthrie’s 26 Columbia River Ballads, commissioned in 1941 by the Bonneville Power Administration. This was musical reportage on one of FDR’s New Deal projects.)

In the words of Robert Shelton, who edited a collection of his writings and drawings that was published in 1965, he was “the archetypal American troubadour, a singer, tale-teller, poet, prophet-singer, roustabout, organiser, union man, traveller, journalist, preacher, hitchhiker, rambler, migrant worker, refugee . . . equal parts Whitman, Sandburg, Will Rogers and Jimmie Rodgers”. Inspired by Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory, Dylan had hitchhiked to New York to meet the man he described as his last idol, unaware that he was slipping into his final days. He died in 1967 from Huntington’s disease.

Guthrie chronicled the Great Depression as it ruined swaths of the United States. In poems, in songs and in "Woody Sez", his column for the Daily Worker, he wrote about the Dust Bowl refugees and migrant farm workers, the poor and dispossessed, the “little people” taught to believe they were “just born to lose”. The issues he wrote and sang about are as pressing now as they were then. Has anyone summed up our current crisis better than Guthrie did in “Pretty Boy Floyd”, a Midwestern Robin Hood story (“Some will rob you with a six-gun,/Some with a fountain pen”)? Dylan, writing six decades later in Chronicles, called Guthrie “the true voice of the American spirit”.

As far as “This Land” is concerned, it started life as a response to the schmaltz of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” which was scarcely ever off the airwaves in 1940. Santelli shows the song’s slow evolution, the first draft written in a loose-leaf notebook on 23 February that year as “God Blessed America”, its architecture largely in place but each verse concluding “God blessed America for me”. By 1945, Guthrie – seemingly unaware of the song’s power – was calling it either “This Land Is My Land” or “This Land Was Made for You and Me”. Only when it found its way into school songbooks in 1957, seen as “the perfect musical counterpoint to the evil communist empire”, was its title settled, nobody is sure by whom. In 1972 United Air Lines used it for an advert; that year, George McGovern quoted it in his speech accepting the Democratic presidential nomination.

The biggest performance of the tune came in January 2009, when Bruce Springsteen and Pete Seeger, who worked with Guthrie and had done much to keep his songs and spirit alive, led thousands on the Mall in Washington to sing along at the concert marking Barack Obama’s inauguration. They looked beyond the “golden valley” and the “diamond deserts” to a land that had been annexed and privatised, its citizens marginalised – singing, in prime time, the two rarely performed verses of Guthrie’s original about “my people . . . as they stood hungry” outside “the relief office”, about “a big high wall” and a sign saying “Private Property”.

As Santelli writes: “No other American standard at the same time praises and dissents, celebrates and castigates, loves and warns”. And no other song speaks more eloquently for today’s 99 per cent. l

Liz Thomson edited, with Patrick Humphries, the revised and updated edition of Robert Shelton’s “No Direction Home: the Life and Music of Bob Dylan”

Spread the word