From earliest childhood we know the stereotypes of Christmas—gifts, turkey and pudding, decorations, snow, festivity and drink. Yet the very familiarity of Christmas and its yearly occurrence tend to preclude a critical and full understanding of its role in our society. Moreover it might appear excessively morbid to lay the cold hands of analysis on what is par excellence the occasion for lighthearted enjoyment and alcoholic oblivion.

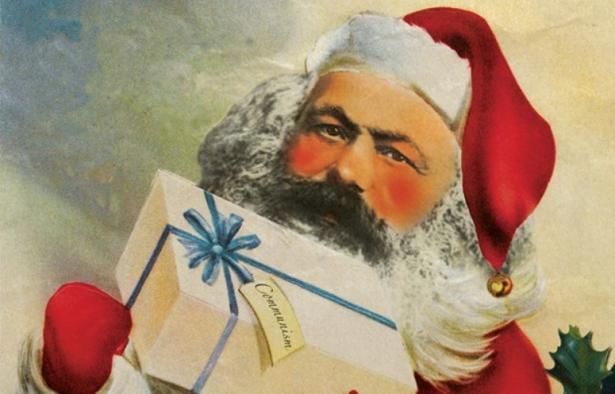

But this very universality and magnitude of Christmas make it the major communal festival of late-capitalist society, lived by all and understood by none; and the festivals of late-capitalism, no less than those of feudal and tribal societies, serve important functions in preserving the cohesion and unity of those societies. They are occasions of exuberance in a world of repression, and so they are both festivals in spite of repression and festivals of repression. The release of counter-repressive feeling in social ritual reinforces the power of oppression as society marshals spontaneous feelings of freedom in order to reinforce its own unfree ideology and structure. At the same time these festivals are a recurring proof that it is possible to overthrow repression if the liberating forces in society are released in a different way and the yearly return of Christmas is a yearly reminder of the possibility of overthrowing the society we have and replacing it with an other. Herein lies the dialectic of Christmas.

The cultural forms now surrounding Christmas are the result of thousands of years of accumulation of myth and symbol, and as each epoch bequeathes its symbols to the next the meaning is transformed and shaped by the new social systems which adopt them. In the case of Christmas all kinds of pagan, Roman, Persian, Jewish, Celtic, Teutonic and Christian elements have been mixed up to produce the festival as we now know it. Although to day we are oppressed by the weight of Christmas as fixed tradition, its form is determined by a long historical and social evolution. Yet its very origins are based on myth and falsehood. Christmas is alleged to be a Christian festival, celebrating the birth of Christ, the son of God, on December 25th in the year 0. The historical Christ was not born in December, but in June or July; he was not born in the year 0 but just before, or just after; and Christmas is a pagan festival used by early Christians as a means of diverting pagan loyalties in to following the new religion.

Christ was born in Bethlehem, Joseph’s hometown, where his parents had gone for a census, because people in the Roman empire had to go to their home towns to be registered when there was a census. Roman censuses were conducted in the summer—when it is easier to travel —and there were ones just before and just after the year 0, not in that year itself. The celebration of a festival of festivity and rebirth in late December is found in many pagan societies. The basic astronomical factor involved is the winter solstice—around December 22—when the days start to get longer. The Romans celebrated the period December 17-24 as the Saturnalia, an occasion for feasting, dancing and dressing up. In the north, including Britain, there was a more sombre festival of Yule when fertility rights for the coming year were celebrated; part of this consisted in the making of special rich food s—the origin of the modern turkey and plum pudding. In ancient Persia, the sun-worshippers celebrated the feast as that of the rebirth of the sun, invincible and a saviour.

Although Christianity itself is obviously the product of previous religions of the ancient world, the early Christians them selves did not celebrate Christmas as a major festival until the fourth century. At that time two oriental religions, Christianity and Mithraism —a sun-worshipping cult—, were competing for the following of the suppressed classes and peoples of the decaying Roman empire. The leaders of Christianity decided therefore to adopt the pagan date and to celebrate it as the birth of Christ and an occasion of rejoicing, hoping thereby to win followers of Mithraism and Roman religion. Instead of the celebration of Saturn or of the birth of the sun as saviour, they worshipped Christ as saviour. (This adoption of pagan symbols for Christian purposes was common. The halo was also taken straight from Mithraism as a symbol—the sun—of divinity; and the crib was borrowed from the cult of Adonis, also alleged to have been born in a stable.)

Sex and Class

Since this early tactical move in the politics of conversion, Christmas has picked up all sorts of other cultural symbols, and has served different functions of the different societies in which it has flourished. The Jewish festival of lights, Hanukkah, led to the practice of putting up coloured lights at Christmastime—although the fact that it is dark a lot at that time of year must also have helped. Another addition came from the feast of St. Nicholas, celebrated on December 6th. St. Nicholas was an early Christian bishop, patron of scholars, sailors and children—as well as of Czarist Russia. His patronage of children and relation to giving gifts are derived from two grossly ideological legends about him. According to one, some little rich boys were killed by a wicked butcher who chopped them up and pickled them; St. Nicholas stuck them together again and returned them to their parents alive and well. Another story concerns a merchant who was suddenly thrown into poverty and was going to sell off his daughters as prostitutes, when along came St. Nicholas in secret and gave them the dowries they needed to marry according to their station. The latent sexual and class content of these legends is obvious. However, in the Anglo-Saxon world at least, the giving of presents was transferred from December 6th to Christmas Day, while St. Nicholas himself was banalised and secularised in to Santa Claus—an American corruption of his name in Dutch.

Christmas as we now know it took shape in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The eighteenth century coaches and houses on cards reflect its early congealment; the growth of cards with the expansion of the cheap post in the 1860s, and the popularisation of the Christmas tree by Prince Albert are later additions. What we now have is this complex totality of myths and symbols, but their varied origins are subordinate to the function which Christianity serves for the preservation of late-capitalist society. It is not merely cultural inertia or human nostalgia that enables Christmas to be celebrated each year—but the inner dynamic of capitalist society itself.

Ideology

First of all Christmas serves to reinforce certain crucial ideological ties in bourgeois society. The two central figures of feudal society—monarch and Pope—are both given special billing at Christmastime, this time in the service of capitalist mystification. (The cancellation of the Queen’s message this year is only a result of over-exposure earlier in the summer.) Their messages stress the unity of Church and Empire. Christmas may be experienced as a predominantly secular occasion but religious ideology is trumpeted through the radio and TV programmes, carols and culture of the period; and the once yearly visits to Church to witness the spectacle serve to blunt materialist consciousness in young and old. The boosting of monarchic ideology is also an intrinsic part of Christmas. The myth of “Christ the King” is found in a plethora of carols and cards, and if this is not enough there is always Good King Wenceslas, tossing crumbs to the Bohemian peasantry. The temporary and mystified resolution of social relations in the Wenceslas carol is found in all kinds of festivals of this period. In ancient Rome slaves were temporarily freed during the Saturnalia; landlords in Russia would give their serfs presents at Christmastime; and this ideological suppression of class relations finds its modern drunken embodiment in the office p arty and the factory dance.

More generally Christmastime is characterised by the ideology of “peace on earth” and “goodwill to all men”. How ever genuine and deep these aspirations are they also serve to displace the need for change on to an abstract wish, or on to a spiritual saviour. They obscure the need for conflict if peace and goodwill are to be possible. A universal awareness of crisis is dissolved in to passive fatalism, and benign idiocy.

At the same time as the public structures of mystification are reinforced, the private structure of the family is strengthened. However antagonistic the relations of parents and children, how ever real the differences between them, Christmas is a time to forget them. The violence of familial relations is drowned in a quagmire of nostalgia and maternal cooking. The Christmas dinner witnesses a crescendo of bad faith and deceit forced on the individual by the pressure of familial ideology and introjected guilt at any violation of the tradition. This is helped by the definite return to childhood relations in this period —a reinfantalisation that both serves to protect the myths of the family, and m ore generally prevents the individual from winkling out the liberating potential of Christmas. While a false celebration of man’s salvation takes place round the spiritual altar of the Church, a real celebration of his repression is found at the material altar of the Family—the Christ as dinnertable. As he reaches out to a non-existent spiritual liberator, he is stabbed in the back by the knife that carves the family turkey.

Money

A second major function of Christmas is quite simple: it is good business. The first signs of approaching Christmas are the tinsel and decorations in shops. The period before Christmas is colloquially measured in the idiom of the market as “x shopping days before Christmas”. 12.5% of all retail trade is done in December alone. By mid-November the media are full of advertisements urging people to buy their wares, and one MP recently urged the President of the Board of Trade to ban the advertising of toy manufacturers because “it causes embarrassment to lower paid workers and widows with families” (The Times, 27.11.69). Instead of gift-giving being a spontaneous act it is surrounded by capitalist pressure; the value of gifts is often measured by how much they cost; and the up-tight nature of relations between parents and child is perhaps reflected in the fact that they can only give at one institutionalised period, and even then they often have to divert the giving through a mythical Santa Claus.

The third aspect of Christmas reflects the repressive channelling of the liberating emotions and forces in society. Christmas has inspired some of the greatest works of western music and painting, and no one can deny that Christmas expresses the deepest aspirations of suffering men—a longing for peace, happiness, good food, social equality and free giving of commodities. In the deepest winter and at the end of the year all these forces are annually released. The expression of these liberating emotions is how ever controlled by social ritual as it has been since pre-historic times. Far from finding their fulfilment in a liberated society they are diverted to reinforce the structures of oppression. The function of myth is to provide diverting solutions to real problems, and the function of ritual is to provide a controlled way in which human emotions can be resolved without destroying the structures against which they are reacting.

The liberation of Christmas is controlled by the very institutionalisation of its expression. People should be able to choose when they rave it up and give presents and love each other: yet Christmas ordains and ritualises them. One is pressured in to celebrating these at one date in the year to stop one from expressing them for the rest of the rest of the year. The expression of freedom in this form is an expression of unfreedom. The happiness of Christmas masks the misery of society. The infantilisation of Christmas time, and the torrents of gross ideological gibberish put out at this period, also serve to blunt any awareness of critical content and revolutionary potential.

The critical creative and aesthetic faculties are assaulted by the awful level of Christmas decorations, cards and other paraphernalia; yet one is blackmailed into submission by the very “traditionality” of it. The lights across Regent Street sum this up—linking Soho to Mayfair: instead of suggesting the end of the class relations on which the shops of central London are based, these decorations attempt to cover them in a meretricious adornment. The overconsumption and frenzied drunkenness of Christmas also serve to divert critical awareness of what is involved. Moreover the social implications are reinforced by the fact that Christmas is experienced in an atomised and enclosed manner. Everyone is at their family lunch. The streets are never so empty as on Christmas Day. The real social unity of the nation and its common acceptance of this extraordinary ideological festival are concealed; the only unity is via TV. Church, the Queen and Billy Smart’s Circus are the focuses of external attention. Hence while all are socially unified in this observance of Christmas, its conscious unity is projected on to the most absurd actors of late-capitalism —Gods, Queens and clowns. Last year the Americans gave us an added spectacle by sending men round the moon, but this fitted neatly in to the general pattern.

Transcend

Here lies the dialectical significance of Christmas. Jesus Christ was once seen as a militant saviour. Christianity was once a revolutionary ideology, but has long been the tool of oppression and myth, and except in the case of revolutionary priests in Latin America it serves to reinforce capitalist society. The desire for happiness is marshalled to defend the instruments of misery and the ideological symbols of myth are carefully used to drown the critical and liberating content of the Christmas festival. To smash the institutionalisation of happiness is to release m en from myth, from the need to displace salvation on to Gods or charity, and to realign man’s hopes on conscious historical action.

Within the apparently innocuous shell of Christmas is found both oppression and the longing for liberation and revolution. The Puritans banned it; the Cubans postponed it; we can transcend it. This involves the release of the revolutionary potential now marshalled by late-capitalist forms. In the meantime, we can, of course, enjoy it.

[Author Fred Halliday, an Irish-born writer and translator, was a long-time editorial board member of New Left Review and the prolific author of numerous books on international relations, including Arabia without Sultans, The Making of the Second Cold War and Shocked and Awed: How the War on Terror and Jihad have Changed the English Language, the latter published shortly after his death in 2011. The Black Dwarf was a short-lived but insurgent, vibrant and highly readable New Left biweekly out of Britain from May 1968 to January 1970. The complete collection of the paper is available HERE.]

Spread the word