I just learned that my old South African friend Jabulani Jali died a few months ago.

We had first met in Lusaka, Zambia during the 1980s when I worked for the African National Congress (ANC) at its headquarters in exile. I knew him then as “Wiseman Goldenway” and I did not learn his true name until years later. Wiseman/Jabulani, like all ANC activists who were not publicly known in South Africa, had adopted a nom de guerre to protect his family back home.

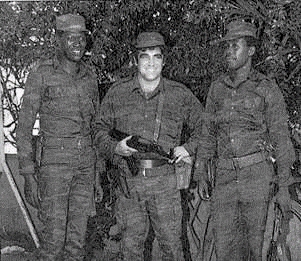

Photo: Jeff Klein

But he was known by another name too. As we moved around Lusaka, we often met fellow ANC members who greeted him as “Yahabibi.” How that nickname came about tells something about the life of my friend – and also attests to the close ties between the freedom struggles in South Africa and Palestine.

In the late 1980s I was helping to organize a number of projects in Lusaka, focusing on technical collaboration with various ANC departments. My own work was mainly with the uMkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation, commonly referred to as “MK”), the armed wing of the ANC. (My route to working for the ANC was rather circuitous, from New Hampshire, to Boston, Nicaragua, and then eventually to Zambia – a story whose details are perhaps better told another time.)

Wiseman/Jabulani was the chief operations officer for MK military and clandestine communications in Lusaka. I didn’t learn his full story until much later when I visited his South African home in 2012. ANC-MK members were extremely reticent about personal details and one didn’t ask too many questions in those days.

Jabulani grew up in Alexandra Township, Johannesburg, the child of a “colored” mother and an ethnic Zulu father. In 1976, like other black South African youth, he was caught up in the SOWETO uprising, sparked initially by changes in the Apartheid policy that would have imposed Afrikaans as the main medium of instruction in “Bantu education.” In 1978, he joined thousands of others who made their way out of the country to join the banned ANC. Given a choice between school or MK, he chose military training for the armed resistance to Apartheid, which was swelling in those years. That’s when he became “Wiseman Goldenway.”

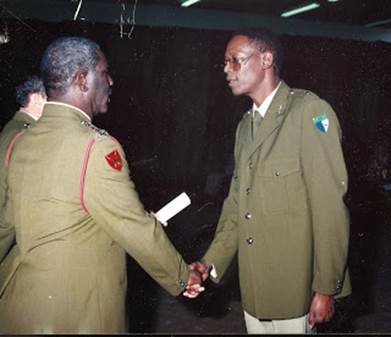

Photo: Ronnie Kasrils, “Armed and Dangerous”

Wiseman/Jabulani was sent with 100 other ANC recruits for military training in the Soviet Union in 1978. He travelled secretly under the assumed name of “Cristiano Monteiro” from Luanda, Angola via Moscow to a military camp at Perevalnoye, near Simferopol in Crimea. This was an international camp for Russian, FRELIMO (Mozambique), SWAPO (Namibia), ZAPO (Zimbabwe), Palestinian/PLO and Lebanese recruits. The different nationalities shared the same high-rise barracks, with each group occupying its own floor.

Wiseman/Jabulani apparently had a lively and outgoing personality then as later when I knew him in Lusaka. He recounted how he became especially friendly with the Palestinians at Perevalnoye,

“It so happened that in the mess hall we were all mixed together so I became friends with the Palestinians. I learned some Arabic. Two guys knew English — they taught me some Arabic, mainly swear words. All the time they were calling me ‘Ya Habibi, Ya Wiseman.’ So our people picked up that Ya Habibi and they thought it was a name. I knew what it meant, ‘My Loving Friend’ but all the ANC people began to call me Yahabibi.

My Palestinian friends were ‘Nasir’ and ‘Muhammed Ali.’ Those weren’t their real names. Muhammed Ali was tall and black, so he was called after the champion boxer. When we were ordered to ‘fall in’ according to our groups, the Palestinians — they are real anarchists — would take me out of my company, put Muhammed Ali with the ANC and put me in his place with the Palestinians. ‘Inte — you are — Muhammed. Ali,’ they told me. My commander knew they were changing us and the Russians knew too. They laughed about it.”

Wiseman/Jabulani completed an intensive 10-month course in “signals” – that is, military communications. When he returned to Angola he became a trainer and specialist in radio for the ANC camps and also with the Angolan army (FAPLA, the Peoples Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola) in their fight agains U.S.-backed UNITA guerrillas and South African Apartheid invaders.

During the the famous series of battles around Cuito Canavale in Southern Angola in 1987-8, Wiseman, with his ability to monitor the South African communications in English and Afrikaans, worked as a radio operator with the Cuban and Angolan forces defending the city. The Apartheid military was fought to a standstill at Cuito Canavale and eventually they withdrew their troops from Angola as part of an agreement that led to the independence of Namibia.

The prospect of an independent Namibia as well as the tightening of international sanctions – the U.S. Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 over Ronald Reagan’s veto in October 1986 — spurred the South African’s government to negotiate seriously with the ANC for a transition from Apartheid to majority rule. But the interregnum between the release of Nelson Mandela from Robbin Island and the first democratic national elections was more violent and turbulent than is usually recognized.

Part of the fraught negotiations during this period were for the integration of MK fighters into the new South African National Defense Forces. In 1994, Wiseman, now Jabulani Jali, was commissioned as a Lt. Colonel. After the first free elections in South Africa, the head of MK, Joe Modise — “Comrade Commander” as we knew him (or simply “JM” to distinguish him from Joe Slovo, who was “JS”) — became President Nelson Mandela’s first Defense Minister.

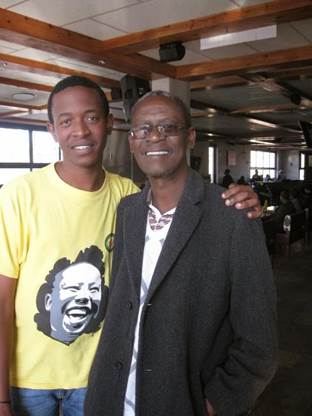

Photo: courtesy of Jali family

When I was eventually able to visit South Africa in 2012, Wiseman, now Col. Jali, was residing with his family in a formerly Afrikaaner neighborhood of the capital, Pretoria. Under Apartheid, no black South Africans were allowed to live there. Jabulani’s neighbors were also mainly military men and they were all keenly interested in the situation of the Palestinians. They recalled bitterly how the Israelis were the principal Apartheid sanctions-breakers during the 1970s and 80s, supplying South Africa with banned weapons and military know-how, including missile and nuclear technology. When I spoke with them about the Palestinian experience, more than once the comment was “That sounds like our history.” It’s no accident that the South African BDS movement is among the strongest anywhere.

Jabulani and his friends also spoke about how the new democratic South Africa fell short of the hopes many of them had for post-Apartheid society. The right to vote in a non-racial country was no small achievement, but economic power still remained with the old white-owned corporations, now with a sprinkling of black faces in the board rooms. Poverty, substandard housing and disastrously high unemployment are still urgent problems in the townships, despite the political emancipation that was achieved with the end of Apartheid 24 years ago.

This was highlighted when we visited Atteridgeville, a township near Pretoria, for Youth Day on June 16. Youth Day is a national holiday now, memorializing the beginning of the SOWETO uprising and it is a celebration second in importance only to Freedom Day, which marks the date of the country’s first non-racial democratic election on April 27, 1994 that made Nelson Mandela president of the country.

Local youth led the way in Atteridgeville, with a message of “Back to Basics” calling for more government support for education, job creation, improved public services and decrying government corruption. Here the young people still idolized former ANC Youth leader Julius Malema, despite his expulsion from the ANC for his fiery populist rhetoric, strident attacks on the established party leadership – and his sometime veiled threats of violent protest.

Photo: Jeff Klein

Col. Jabulani, now a respected elder from the SOWETO movement and a revered MK veteran addressed the young militant crowd of young demonstrators: “I’m old now. People of my generation laid the groundwork for you young people, who have grown up in a democratic South Africa. But the work of building a truly free and just country has a long way to go.” He added: “The future is up to you. The torch is yours to carry.” The young crowd cheered.

Photo: Jeff Klein

During the ride back to Pretoria, where once only whites were allowed to live, we talked about the larger significance of the Soweto youth rebellion – and not just for South Africa.

It was hard to disagree with the words I read the next day, in City Press column by Sibongile Mkhabela, director of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund:

“The 1976 uprising was a wake-up call to all sectors of society. It gave new meaning to the spirit of resistance, the civil rights movement and black power among communities in South Africa and elsewhere — including that bastion of white supremacy, the United States… We have not yet reached the end of our journey.”

But, sadly, my friend Jabulani/Wiseman, — who gave his entire life to the freedom struggle — will not live to see that day.

Rest in peace Yahabibi.

[Jeff Klein, is a retired local union president, a long-time Palestine solidarity activist and a board member of Mass Peace Action. He has a blog. Other posts by Jeff Klein.]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word