It was the first truly warm day in New York City since autumn and kids snaked up Central Park West by the hundreds.

High school students, squads of 8- and 9-year-olds, parents with strollers and pre-teens grasping hands marched from Columbus Circle to the Natural History Museum on Friday afternoon, passing Trump International Hotel & Tower on their way, to demand radical action on climate change. They joined a chorus of young people across the United States and around the globe who walked out of school Friday in an international strike for climate action — reportedly the largest protest against global warming in human history. An estimated 1.4 million people in 123 countries took part.

“This is powerful because it’s a global movement,” 17-year-old Yosef Ibrahim yelled into a megaphone at City Hall in Manhattan, where the day’s actions began. “Every half degree you go up, that’s islands being destroyed, hundreds of millions of people becoming refugees.”

As New York City’s youth flooded the streets, more than a million others did the same across the continents, from India to Argentina to China. Waves of students stood together in capital cities like Washington D.C. and Seoul and Cape Town. In places as small as the village of Carrick-on-Shannon, in County Leitrim, Ireland, a single student walked out of his school alone to join the protest.

The global climate strike began as just this sort of action: one student standing up. Sixteen-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg started picketing outside of the Swedish Parliament every Friday last year to demand swift and radical action to stop climate change rather than attend classes. Thunberg’s weekly strike — as well her viral dressing-down of politicians at the U.N. climate summit in Katowice, Poland and the Davos World Economic Forum — quickly gained attention in the press and on social media. Kids began their own weekly actions. The movement spread across Europe, the United States and the world, and Friday’s strike was born. Just days before the protest, Thunberg was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Never let anyone tell you that just because you’re a kid you can’t make a difference,” one youth speaker told other students at City Hall. “You all have your inner Greta Thunberg.”

Throughout the protests in New York and on social media posts from around the globe, student after student spoke out Friday and made their message clear: this was protest born of rage.

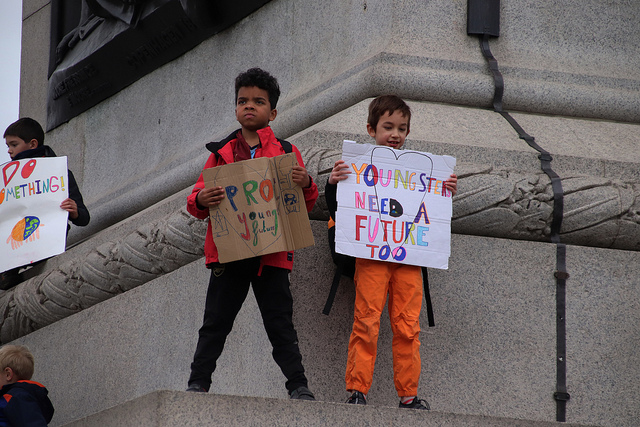

The mass demonstration is part of a wave of youthful resistance over the past decade. It comes nearly eight years after Occupy Wall Street exploded at Zuccotti Park, two years into Donald Trump’s presidency and a year after hundreds of thousands of children joined the March for Our Lives, demanding Washington pass stricter gun laws over objections of the National Rifle Association. Like their anti-gun counterparts, the climate kids are fighting for their lives and naming the guilty parties without flinching: corporations, politicians, and the 1 percent. The activists were young, but they were not cute. And they were determined.

“I will not sit in a classroom, I will not apply to college while our world is dying,” said Mary Catherine Fitzgerald, 16. “Politicians have made it very clear they don’t want to take action. If they don’t take action, we will.”

The striking students demanded a moratorium on fossil fuel extraction, the end of single-use plastic, greater education about climate change for young people and a comprehensive Green New Deal. They want politicians to start listening to their constituents — even the ones not yet old enough to cast a ballot.

Credit: Roy/Flickr // The Indypendent

The international demonstrations were the result of careful coordination on the part of young people through social media across incredible distances. Thirteen-year-old New York City resident Alexandria Villaseñor, who has been striking outside the United Nations headquarters every Friday since December, coordinated the U.S. protests alongside Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s daughter Isra Hirsi in Minnesota and Colorado middle-school student Haven Coleman.

“Today you are hearing from children all over the world,” Villaseñor said. “We are telling you we are trapped and the time has come for you to turn the furnace off and save us all.”

Some strikers had never attended a protest before. Students taught each other chants and worked together to coordinate when the demonstrations hit roadblocks. At City Hall, when high school senior Tasnim Emu saw students weren’t speaking up, she grabbed a megaphone and began lining up protesters to give speeches. Uptown at Columbus Circle, when confusion spread about where the protesters should go next, students worked together to spread the word that they’d be marching to the Natural History Museum. A few organizers decided the best way to share the plan was to start a call-and-response chant. Bull horns were passed around and the tide of demonstrators began to march.

Credit: UNEP // The Indypendent

Again and again, students urged each other to stay involved after the daylong strike was over. 16-year-old Sylvana Widman asked students to take their demands to Albany, where she’s been pushing for the Climate and Community Protection Act to transition New York to 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. Her friend Lena Kassin navigated the rush of protesting kids with a clipboard, asking them to join the Sierra Club.

Five-year-old Camilo Budet Trescott held a sign nearly as big as his body demanding that adults stop polluting. He raised his fist to the sky while cameras flashed, revealing an arm covered in ink, scrawled with the words “SAVE THE PLANET.”

[Libby Rainey is a Democracy Now! reporter who covers criminal justice and immigration. Her work has appeared in The Denver Post, The San Francisco Chronicle, Citylab, Los Angeles News Group, and Southern California Public Radio. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Literature from the University of California, Berkeley and a Master’s degree in Modern & Contemporary Literature from the University of Cambridge. She has reported from within prison walls as an advisor for The San Quentin News, an award-winning newspaper at San Quentin State Prison produced by incarcerated journalists, and the Solano Vision, a newspaper produced by incarcerated reporters at Solano State Prison. She was a researcher and editor on Professor William Drummond’s forthcoming book on the history of prison journalism, to be published by UC Press.]

The Indypendent is a monthly New York City-based newspaper and website. To subscribe to the print edition, click here. Support great independent journalism. (One-year subscription - 12 issues (mailed monthly to U.S. address. Click here.)

Spread the word