Danielle Atkinson, head of Mothering Justice in Detroit, Michigan, is clear about the priorities of the black mothers in her network. Their needs run the gamut — decent pay, health care, affordable housing, quality child care and education, equal opportunity. Threaded through all these issues is the urgency of time for caregiving. “Paid time to care is a big deal if you have young kids and a mom with Alzheimer’s and you’re trying to keep your job,” Danielle said. “It’s the difference between holding it together and everything falling apart. Yes, we need $15 an hour — but you can’t earn $0 an hour because you had a baby or your parent is dying.”

As the recent government shutdown revealed, even many middle-class people live paycheck to paycheck. The loss of income for just a few weeks forced federal employees to pawn favorite possessions, ration insulin, and use food banks. At least most of those folks are getting their back checks. People without wages during leave never get repaid — and some never catch up. Lost pay, at times accompanied by loss of a job, can mean a spiral of debt, bad credit, and years of struggle just to keep your head above water. The face of that loss is typically female, immigrant, of color — those already facing a stacked deck in the U.S. economy.

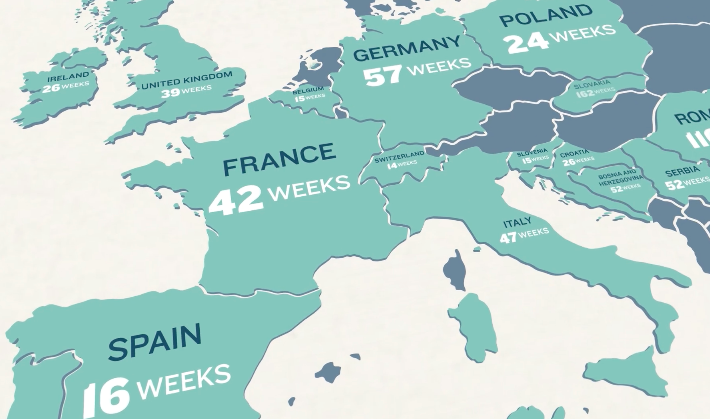

In fact, only 17 percent of all working people have paid family leave through their job. Many people are shocked to learn that our nation is the only advanced country and one of only two countries in the world that has no paid leave policy. Our network of state coalitions is working hard to change that.

The federal policy we’re organizing for is known as the FAMILY Act. Sponsored by Rep. Rosa DeLauro and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, it would pool small contributions from employers and employees to provide up to 12 weeks of partially paid leave to bond with a new child, deal with a serious personal or family illness, or with needs that arise from a military deployment. The length of leave pales in comparison to what’s offered by many companies and virtually all industrialized countries. Yet while basic, it is also bold and transformative, the first new social insurance program in the U.S. since the New Deal.

Enacting paid family and medical leave in the U.S. will begin to value caregiving and reverse centuries of inequity based on forced and devalued care provided by women and people of color. Paid leave will make it possible for people — regardless of gender — to cherish the first months of a child’s life and enrich the last months of a beloved parent’s; to heal and thrive from their own injury or illness; and to spur the recovery or ease the suffering of a loved one. No more having to abandon a preemie in the NICU; no more chemo on your lunch break; no more teenagers quitting school to take a job at McDonald’s because a parent got fired for having leukemia. Meaningful paid leave in the U.S. will be a vital part of eradicating poverty and boosting family stability. And it will make businesses more robust by reducing turnover and increasing consumer solvency.

Passing paid leave is within our reach. To impact those who need it most, we need to embrace what the FAMILY Act already contains and add a few new provisions based on what we’ve learned from wins in six states and the District of Columbia that have paved the way for federal action.

First on the list, the rate of wage replacement. Low-paid workers can’t take the leave if the percentage of wage is too small. We need to adopt a progressive wage replacement rate, as Washington, D.C., Washington State and Massachusetts have done, so that the lowest earners receive the highest percentage of their pay. Likewise, we can’t expect people to take a leave if their job will disappear when they return to work. Following the lead of Rhode Island and New York, we need to ensure that all leave-takers have job protection. And our program should value every family by having an inclusive family definition such as the one New Jersey has just adopted that recognizes the reality of family formations, including chosen families. We also need to ensure that 1099 earners are included; Massachusetts’s law requires employers who issue 1099s to more than 50 percent of their workforce to contribute to the fund for those individuals.

We can make these pieces affordable by lifting the salary cap on the wage base of employee contributions — as Social Security advocates have long pointed out, why should workers paid below a certain level make a contribution on every dollar earned while high earners contribute only on a portion of their salary?

Extensive evidence underscores the range of benefits from caregiving time that is affordable, of adequate duration, and accessible to every working family. Enacting paid leave should be a no-brainer. But make no mistake: To pass this law, we’ll have to overcome major hurdles both from opponents and from some who consider themselves supporters of paid leave.

Hurdles to Passage

People always ask us why it’s taken the wealthiest country so long to catch up with the rest of the world. In the documentary Zero Weeks, a member of the Spotify team working on a paid leave playlist wants details on paid leave in the U.S. When she hears “zero weeks,” her jaw drops. “How can that be?” she asks. “In my country, Spain, we have four months and we think that’s too little.” Popular culture is beginning to echo this sentiment. On Grey’s Anatomy, a pregnant Dr. Teddy Altman wonders whether she should return to Germany where they have great maternity and paternity leave.

We can talk about the culture of American individualism, the ways people are made to feel these are personal problems they have to cope with on their own. But the chief reason the U.S. is an outlier is the role of corporate lobbyists who spend a lot of money spreading misinformation about risks and putting pressure on decision-makers to stay out of the way of big business clients.

We know these lobbyists well. We’ve successfully taken them on to win state policies — both paid family and medical leave and paid sick days, and we’re prepared to do the same for the federal fight. One of our best tools is their own words after we win — like the VP of the Golden Gate Restaurant Association who led the fight against paid sick days in San Francisco in 2006, then told a business reporter four years later, “It’s the best policy for the least cost.”

Leaks help. In a private study, conducted by Republican strategist LuntzGlobal among Chamber of Commerce member businesses, that was leaked to the media, 82 percent of respondents supported policies like paid paternity leave, and 73 percent supported more paid sick time.

Reality helps as well. We remind legislators how wrong were those who predicted doom as a result of the unpaid Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), signed into law in 1993: Rep. Rodney Gaines of Minnesota, for instance, warned of “estimates that tens of thousands of working men and women will be put out of work if this bill passes.” Rep. John Boehner of Ohio proclaimed that law would “be the demise of some [business owners]. And as that occurs, the light of freedom will grow dimmer.” We also share the strong case that many business leaders and experts have made for paid time to care.

The more complicated challenge is those who say they support paid leave but pressure us to settle for some narrow, meager bill. They tell us not to let the “perfect” get in the way of “the good” and scold us for reaching too high. To them, the decent floor in the FAMILY Act is idealistic and too far to the left. Instead they urge to start with a “slice” — six or eight weeks just for parents of new children, from an unacceptable source like early withdrawals from Social Security, such as Sen. Marco Rubio has proposed.

In fact, time just for parents of new children leaves out 75 percent of those needing care. The thousands of people who have become activists in campaigns for the state bills have a clear response to the “slice” argument: “Don’t cut me out.” The administration calls such a policy family leave, but it’s not even parental leave. It wouldn’t cover parents like Staci Lowry, who lost her job and her home when her four-year-old daughter had a stroke, or Blue Carreker, whose teenage son had to endure multiple spinal injections and chemo side effects alone because Blue and her husband had no paid leave. The Rubio bill has nothing to offer those caring for a parent, like Kris Garcia, who had to make painful decisions about life support for their father over the phone. And it ignores the largest group, those who need to care for themselves — people like Stephanie Tucker, who had to work during radiation even when her skin was burning because “You tell the car company you’re going through cancer treatment, and they still say, ‘When can you pay?’” Even many new parents would be unable to use the Rubio bill because the price of having some income at the time of the birth or adoption would be delayed retirement and a cut in Social Security benefits. Such a plan would have the most negative impact on low-paid workers who may have no source of income but Social Security in their later years.

How Long for Another Bite at This Apple?

As for that “slice” approach, it’s been 26 years since a president signed the last (and first) piece of legislation on family leave, the Family and Medical Leave Act — and that measure took nine years to become law. We can’t wait another third of a century for the next slice, the stakes are just too high.

Back in 1993, the FMLA was an important first step, affirming three key principles: Having a family shouldn’t cost you your job or your health insurance; caregiving protection should be gender-neutral; and newborns or newly adopted children aren’t the only ones needing care. The FMLA, which provides for up to 12 weeks unpaid leave to welcome a new child or care for a serious personal or family illness and return to the same or equivalent job, has been used more than 200 million times. Still, FMLA falls far short of what’s needed. Because it covers only those in companies of 50 or more and because of eligibility requirements that knock out many part-time workers, a good 40 percent of the workforce isn’t protected. And millions who are covered return to work too soon, forego treatment or wind up in serious debt because they can’t afford to take the time without pay. For those caring for a loved one with a disability, the consequences boomerang. As one caregiver put it, “I needed to have more time to

talk to doctors, understand treatment and medication. We were crumbling, and so was she.”

Bipartisan support

The FMLA passed with bipartisan support, and the FAMILY Act should be as well. We know our movement can do that because we already have in several states. The Senate in Washington was under Republican control when the majority of both parties passed that state’s law, which calls for more time and a higher wage replacement than the FAMILY Act. A Republican governor in Massachusetts signed into law the strongest bill to date. Pennsylvania’s proposal will have Republican sponsors.

We know, however, that there are two ways to get legislators on board. One asks, what do we have to give up? The other starts from a position of power and makes a strong case for why support is in the best interests of the legislator’s constituents — and the legislator’s job.

The organizing approach needed to win the FAMILY Act with the improvements we’ve described is the same our network has used to get those state wins. Here are the key ingredients: leadership by those most affected by the issue; a strong vision and frame of a caring economy and how that benefits everyone; a broad and diverse coalition, including labor and business owners and a full range of stakeholders; political savvy in mapping champions and targets; and a demonstration of power and effective case-making.

The successful campaign in Massachusetts is a good example. They were able to win a bold, inclusive policy with bipartisan support by building power and combining a strong grassroots game with savvy targeting of legislators and smart work in negotiations. Leading the campaign was Raise Up Massachusetts, a coalition of community, labor and faith groups with a leadership team made up of representatives of each sector. The member organizations stayed together after winning paid sick days and a minimum wage increase through ballot measures in 2014. They took the momentum and built on that collective power to organize for another ballot in 2018, this time for paid family and medical leave. The groups gathered all the signatures themselves, not relying on paid vendors but seeing the signature collection as a way for each group to build their membership and develop leaders. They held rallies, convened community briefings, shared stories, highlighted business supporters, and organized phone banking of legislators and constituents throughout the campaign.

According to Deb Fastino, a long-time leader in FV@W who is director of Coalition for Social Justice and member of the Raise Up executive team, the work was successful because of the coalition partners’ collective accountability. “The legislature saw our power since we had the threat of the ballot,” Fastino said. She described the moment when the committee chair lectured the business lobbyist who testified against paid leave, telling him, “You better meet with the coalition or you’ll have no say in the outcome.”

Massachsuetts won the most comprehensive paid leave bill in the country — signed into law by a Republican governor.

The Massachusetts team learned from others in our network who’d already won, including coalition leaders in Washington state. They shared the behind-the-scenes comments of a Republican leader about the arguments that won him over. He had been moved by his own experience as a new father and the recognition of how hard it must be for parents with far fewer resources than his family has. Then he met workers who had become activists in the coalition and understood that kids don’t just get born — they sometimes get ill or injured and need a parent then as well. He saw that even those who aren’t parents have parents or partners or their own health that from time to time need care. So, he agreed to covering not just time to bond with a new child, but the multiple reasons for caregiving. As he learned about the rate of job churning — more than one in five workers had been with their current employer for a year or less — he came to understand that only the government could ensure that paid leave reaches everyone regardless of where they worked. And he saw how paid leave was key to making jobs into careers by reducing the turnover problem.

This legislator also understood politics. “I may not be super smart,” he told us in a private conversation, “but I know how to read a poll. I know what 80 percent support means.”

Today’s Congress is much more partisan and ideological than it was in 1993. That will make it harder to win bipartisan support, but we’re heartened by the growing recognition in both parties of the need, and by the number of state and federal candidates who ran on the issue in 2018. When Family Values @ Work began more than 15 years ago, we and our partners understood this issue was not on the political agenda. Those who cared about ending poverty did not talk about employment, focusing instead on the social safety net. The good jobs movement didn’t mention time to care. Work and family advocates centered on professional, mainly white, women. The women’s movement had other priorities. While unions had led the original fight for paid maternity leave in workplaces, they, too, were focused on other priorities. Candidates did not have this on their radar screen.

Today all that has changed. The movement has also garnered the support of funders like the Ford Foundation, Kellogg and Annie E. Casey. Whether interested in the future of work or the well-being of children or democracy and civic engagement, they see this as an issue important to achieving their mission.

Winning paid leave will be a game-changer for this nation and especially for those facing multiple forms of oppression. As Tameka Henry, who lost a job and over a decade $200,000 because she needed to care for a husband with a disability, put it, ”If a [paid leave policy] had been place, my family would be much better off than we are now. I would have had the chance to have stability and work towards retirement. … It’s like starting from scratch every time you start a job. Families like mine would rather work and pay our own way.”

And that’s not all. The movement we have been building across the country is propelling cohorts of new leaders, many of them women of color and queer and trans folks. Women are gaining agency, men are redefining themselves as caregivers, and LGBTQ communities are getting seen and valued. Huge numbers of people are coming to see the proper role of government in protecting its people. Small business owners are breaking the identity theft of corporate lobbyists and speaking out about policies that will help them prosper. Importantly, in our coalitions people are building bridges across movements. We are adding to critical infrastructure for long-term, systemic change.

In demanding and winning affordable time to care, we are building the power to become the nation we need and deserve.

Ellen Bravo and Wendy Chun-Hoon are co-directors of Family Values @ Work, a national network of coalitions in 27 states working for — and winning — affordable time to care.

Spread the word