Who began the killing? At root, arguments about the genesis of the Troubles are arguments about responsibility for murder, and that’s one reason it has proved so hard to disentangle history from blame in accounts of Northern Ireland since the late 1960s. In May 1974, in the New York Review of Books, the critic Seamus Deane lambasted Conor Cruise O’Brien, then minister for posts and telegraphs in the Irish Republic’s coalition government, for implying in a previous issue that ‘the Provisional IRA began the killing in the North.’

Not so. It was the Royal Ulster Constabulary who did this, using armoured cars and Browning machine guns on unarmed and unsuspecting Catholic citizens in the Falls Road area in 1969. He also states that the British army’s role in the North is, fundamentally, to protect the Catholic population. This was originally so, but to state that this situation persists is a lie.

O’Brien countered that while Protestant extremists and the RUC were indeed responsible for attacks on Catholics in 1969, the deployment of British troops that year, far from negatively affecting the Catholic population, had actually initiated long overdue social and political reforms of the Northern Irish state. Since 1922, when Ireland was partitioned, Northern Ireland had been governed by a devolved parliament, modelled on Westminster but sitting at Stormont in Belfast. Stormont had the power to legislate over nearly every aspect of Northern Irish domestic life, while foreign policy and some central taxes remained the preserve of Westminster. The regional parliament was notorious for its efforts to maintain a unionist majority: even before the end of the 1920s it had dispensed with the original electoral system, which was based on proportional representation, and systematically gerrymandered the boundaries of constituencies to ensure the return of unionist candidates. For fifty years, until Stormont was prorogued by Westminster in 1972, the Ulster Unionist Party was in government. Northern Ireland was effectively a one-party state, operating an institutionalised form of discrimination. Emergency law and order legislation was normalised as a tool to be used against the minority nationalist population. Nationalist and republican marches, publications (including communist publications) and emblems – the Irish tricolour, for example – were frequently banned. The Northern Irish police force, known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary, was armed (unlike any other British force), and overwhelmingly Protestant and Unionist in its composition – a sectarian outfit. There was open discrimination against Catholics in the fields of employment and local housing allocation, which also determined the right to vote in local elections.

By 1969, O’Brien argued, the combined influence of a new generation of more liberal politicians and pressure from the Northern Ireland civil rights movement promised the beginning of equality, and democracy, for Northern Ireland’s Catholic population. And yet, despite the real prospect of peaceful co-existence, the Provisional IRA, the more militant wing of the organisation, dedicated to ending British rule through the use of guerrilla warfare, chose to return to violence. They began the killing again, deliberately provoking confrontation by means of a bombing campaign, and orchestrating collisions between the British army and the civilian population. The result, according to O’Brien, was an increase in Protestant antagonism against Catholics so great that, if the army were now to be withdrawn, Catholics in Belfast would be massacred.

War and an Irish Town

By Eamonn McCann

Haymarket Books, 296 pages

October 30, 2018

Paperback: $16.95 ( on sale $11.86, with free bundled ebook); E-book: $16.95 (on sale $10.17)

ISBN: 9781608469741

ISBN: 9781608469758.

O'Brien had been the Irish Labour Party’s spokesperson for Northern Ireland while it was in opposition, and once in government he was closely involved in implementing the 1973 power-sharing agreement, known as Sunningdale, which aimed to overcome the breakdown of civil society in Northern Ireland by including elected members from both communities in a reformed parliament. It was a clear forerunner of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. O’Brien’s riposte to Deane in the NYRB extolled the possibilities of Sunningdale, but three weeks later, at the end of May 1974, the executive collapsed under concerted opposition from unionists, which included a general strike. Eamonn McCann’s War and an Irish Town was published some months later. It is an account of how the working-class revolution McCann had hoped to bring about in Derry in 1968 developed, by the early 1970s, into sectarian warfare. Reissued last year, to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the October 1968 civil rights march in Derry, it is a study in the messy history of violence. There are no clear beginnings to this story and, as we were reminded by the killing of Lyra McKee on 18 April this year, there is no clear end either.

McCann grew up in the Bogside area of Derry, the son of a trade union organiser. Like Seamus Deane and Seamus Heaney, who were both a few years ahead of him at St Columb’s Catholic Grammar School (where John Hume and Brian Friel had also been pupils), he belonged to the first generation to have access to free secondary schooling after the war. He went to university at Queen’s in Belfast, spent time in London, and by the mid-1960s was back in Derry, fired up by Marxist-Leninist revolutionary ideology as well as admiration for the Black Panthers and the Aldermaston protesters. Later came ‘a Sorbonne-inspired belief in spontaneity’.

McCann describes the atmosphere in the nationalist areas of Derry in the early 1960s as one of resentment and resignation. The city was effectively segregated. (‘No Protestant lived in the Bogside. The Unionist Party had seen to that.’) The Catholic population was openly discriminated against in employment and, especially, in housing. Only householders could vote in local elections: ‘To give a person a house, therefore, was to give him a vote, and the Unionist Party in Derry had to be very circumspect about the people to whom it gave votes.’ Male unemployment in the Bogside hovered at around one-third of the population, even though many had emigrated. Those who stayed lived in some of the most deprived and overcrowded conditions in Europe. Yet, ‘there was no swelling outrage.’ McCann blamed the lack of revolutionary fervour on the combination of a conservative Catholic Church and the cautious politics of the (now defunct) Nationalist Party, which nurtured a sense of grievance against discrimination but had no plan for what to do about it. The resolution of social and economic inequality was postponed to the distant future, to be considered in a united Ireland where Catholics would not only be employed and decently housed, but valued. ‘We recognised that it was not an immediately attainable object, that it was not going to happen tomorrow, but no one ever doubted that someday, somehow, it would come.’ Discrimination was a fact of life: ‘That the resultant miseries could be looked on as a price to be paid for remaining true to the national ideal made them more easily acceptable.’

McCann and his revolutionary socialist allies were determined to change the political culture. In early 1968 they formed a campaign group, the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC), to agitate for an end to housing discrimination. Their tactics included interrupting meetings of the Derry Corporation (‘the living symbol in Derry of the anti-democratic exclusion of Catholics from power’), squatting in empty houses, and picketing private landlords. One demonstration involved dragging a caravan housing a couple with two children onto the main arterial road through the Bogside, bringing traffic to a standstill until the family were rehoused. McCann acknowledges that DHAC resembled ‘a rather violent community welfare body rather than a group of revolutionaries’. In his introduction to the new edition he insists on the international dimension of their work, citing anti-Vietnam protests and the strategies of the Black Panthers, but what comes across most strongly in his original account is the highly localised nature of the campaign. There are only a few glancing allusions to the événements in Paris, and no mention is made of US global imperialism; even the US civil rights movement is a shaky reference point. In July 1968 one of the DHAC protesters began to sing ‘We Shall Overcome’ as they resisted arrest. ‘No one joined in,’ McCann writes. ‘As yet they did not know the words.’

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (McCann refers to it as the CRA) march in Derry on 5 October 1968 is often cited as the ‘start’ of the Troubles. When the RUC blocked the marchers and baton-charged the crowd, the television cameras broadcast the violence to the world. Writing his book in 1973, McCann was extraordinarily forthright in admitting that this sort of confrontation was what DHAC had been angling for. They had invited the CRA (based in Belfast) to organise the march, even though its agenda was not the same as theirs – the DHAC placards called for working-class revolution. They proposed a route through Derry that was bound to be rejected, and were surprised when the CRA agreed to be involved. (This is one of several moments in War and an Irish Town when the distance between Derry and Belfast seems vast. The CRA was simply unaware of local Derry politics, and had no sense of what it would mean for Catholics to organise a march within the city walls.) On 3 October the march was, as expected, banned. DHAC insisted it would go ahead anyway: ‘Our conscious, if unspoken, strategy was to provoke the police into overreaction and thus spark off mass reaction against the authorities. We assumed that we would be in control of the reaction, that we were strong enough to channel it.’ On 5 October they had hoped to draw a crowd of five thousand. As it was, only four hundred people turned up; they were trapped by police cordons and battered on TV. ‘We had indeed set out to make the police overreact. But we hadn’t expected the animal brutality of the RUC,’ says McCann.

By November 1968 Terence O’Neill, the prime minister of Northern Ireland and leader of the Unionist Party, was promising change. His proposals included abolishing Derry Corporation and instituting universal suffrage. McCann argues that if these reforms had come three months earlier, the impetus behind the protests that were by then gathering steam would have dissipated. But now they were ‘too little far too late’. After the shocking scenes in Derry, marches were happening more often and were increasing in size. Faced with violent counter-demonstrations and clear evidence of collusion between Protestant extremists and the RUC in attacks on Catholics, O’Neill’s attempts at de-escalation were never going to be enough. In January 1969 a People’s Democracy march from Belfast to Derry was attacked at Burntollet Bridge a few miles outside Derry, leading to rioting and – as the Westminster government’s hastily convened Cameron Commission investigating ‘Disturbances in Northern Ireland’ concluded a few months later – sectarian attacks by the police on the people of the Catholic Bogside.

Conservative unionists, their privileges under threat, made little distinction between the granting of civil rights and concessions to revolution. Under the Reverend Ian Paisley’s banner of ‘No Surrender’, Protestant extremists fought back. By August, Belfast ‘was desperate … inconceivably horrific’: the minority Catholic population were burned out of their homes and there were pitched battles between the security forces and the nationalist community. Seven people were killed. In the Bogside a ‘Free Derry’ was proclaimed. If the Northern Irish government was going to exclude Catholics from democracy, the Bogside would set up its own democratic fiefdom. The barricades went up in January, then came down, but by August they were reinstated, following an attack by the RUC and members of the Protestant Apprentice Boys, one of the Protestant Loyal Orders: ‘Barricades went up all around the area, open-air petrol-bomb factories were established, dumpers hijacked from a building site were used to carry stones to the front.’ A three-day battle with the RUC came to an end when British troops were deployed. The defence of Free Derry continued for several months, until in mid-October another fast-tracked Westminster committee produced the Hunt Report into policing in Northern Ireland. Baron Hunt, a retired military officer, made 47 recommendations, including the disarming of the RUC and the abolition of the Ulster Special Constabulary (‘B Specials’), a semi-military auxiliary force in the RUC. It was a victory for the community, and it meant the barricades could come down, but in McCann’s account it comes almost as a disappointment. He is full of the excitement of the fight – manning the Free Derry Radio Station, producing Barricade Bulletins, and learning to use weapons. Labour Party members and young socialists began, in September 1969, to learn how to dismantle and reassemble Thompson guns, and how to make Mills bombs. ‘We went across the border into the Donegal hills for practice shoot-outs,’ McCann writes. ‘It was exciting at the time and enabled one to feel that, despite the depressing trend of events in the area [he means the removal of the barricades], one was involved in a real revolution.’ He was 26 years old.

*

Until this point in the story, McCann’s account of the beginning of the Troubles aligns broadly with Conor Cruise O’Brien’s. The Catholic community’s reasonable demands for an end to discrimination were met with a violent backlash, orchestrated by Protestant extremists and supported by a sectarian police force. Major reforms were then wrested from the Stormont government, including the disbanding of the B Specials, votes for all, the repeal of the Special Powers Act. The British army brought peace to the streets. But here agreement ends. For O’Brien the responsibility for the return to violence lay squarely with the Provisional IRA, who fomented trouble in the name of a united Ireland – a demand that had not formed part of any platform during the civil rights campaign. For McCann the question of blame was more equivocal, partly because it lay further back, in structural inequalities, in the economic interests of what he calls ‘the Orange machine’, and in the inglorious history of the Irish Republic which repeatedly, throughout the 20th century, provided Ulster Protestants with ample evidence that they were right in fearing that Home Rule meant Rome Rule. War and an Irish Town called down a plague on both unionist and nationalist houses: both were based on landowning and business-owning class interests and neither, therefore, was willing or able to respond to the needs of the poor. His analysis was couched in the typical vocabulary of the hard left in the 1970s. Unionism, for example, was ‘an ideological refraction of the economic needs of property’, and from the late 19th century onwards it had served its purpose well. But by the end of the 1950s the economic basis of partition was being eroded, and British economic interests no longer lay in bolstering the Northern Irish state, but rather in seeking accommodation with the Republic. (The UK first applied to join the EEC in 1961.) Hence the new language of liberal unionism and the move to concede civil rights. By the mid-1960s the ideology of hardline unionism was in sharp conflict with Northern Ireland’s economic needs. McCann’s language is dated, but his analysis is still current.

Yet looking back from a distance of nearly fifty years what is most striking about War and an Irish Town is the clash between the clarity (and simplifications) of its account of Northern Ireland’s past, and McCann’s confusion over the meaning of the present. He tells a detailed history of the events he has just lived through, including the IRA split in 1970, the growth of republican sentiment among the protesters, the effects of the programme of mass internment in 1971, of Bloody Sunday in January 1972 and the introduction of direct rule from Westminster in March of that year. He acknowledges the part played by ‘old’ republicans, as well as the newer kinds – socialist republicans in the Official IRA, and irreconcilables like Martin McGuinness, who joined the Provisionals. He describes how the British soldiers took on the role of the RUC, until they became indistinguishable from it. (‘The only difference between the army and the RUC was that the army was better at it.’) But the story he tells is also of people caught up in events, rather than orchestrating them. Even as the crisis unfolded ‘outsiders’ kept trying to determine who started it, but for McCann that is the wrong question: ‘The controversies which occupied hours of parliamentary time and acres of newsprint, about which side threw the first stone or whether the soldiers, when the fighting started, had acted impartially – were of little interest to the rioters and potential rioters of the Bogside and the Creggan.’

By 1971, McCann saw ranged on one side, ‘Tories’, the RUC, the army, the military police, Paisley and his supporters, and Stormont. On the other were the moderates, socialists, republicans, and those he calls (without irony) the ‘hooligans’. The initiative lay with the hooligans. In late 1969, with peace on the streets and the legal bases for discrimination ended, the Troubles seemed to be over. ‘None of it, however, made any difference to the clumps of unemployed teenagers who stood, fists dug deep into their pockets, around William Street in the evenings.’ McCann writes about these leaderless, frustrated youths with empathy – after all, he had been excited by the riots too. But his description of the regular battles between stone-throwing kids and British soldiers armed with shields, rubber bullets and CS gas, is a sobering account of how conflict by its very nature begets further conflict. It is a messy explanation, which the authorities didn’t want to hear at the time, and, arguably, haven’t wanted to hear since. In his analysis the ideology of republicanism was secondary to the day to day experience of the riots. A year previously the struggle had been to defend the Bogside and bring Stormont down, but now the enemy was clearly identified as the British state. ‘We Shall Overcome’ gave way to republican songs. ‘People were almost relieved gradually to discover that the guiltily discarded tradition on which the community was founded was, after all, meaningful and immediately relevant.’

Part of the problem was that both sides looked to creed (republicanism or unionism) to solve social problems. In an interview on Irish television in September 1969 Bernadette Devlin criticised the Cameron Report for completely ignoring ‘the central point’ about the disturbances – that the cause of the unrest was ‘basic social deprivation, lack of jobs and lack of houses’. Lip service was paid to the problems of deprivation, but nothing was done. When the Provisionals escalated their bombing campaign in 1971, they were, according to McCann, ‘the frontline hooligans of 1969 in arms, young and urgent and now absolutely sure of themselves, with all the arrogance of their age and their race’.

McCann’s sympathy for the kids extends a long way, even as far as questioning efforts for peace. He describes the women’s peace movement in Belfast with something like disdain: ‘The peace women had emerged, bringing the SDLP along in the slipstream of their petticoats.’ In May 1972 (three months after Bloody Sunday), a Creggan teenager, William Best, was shot dead by the Official IRA while at home on leave from the British army. The killing, McCann argues, ‘gave Catholic Tories the opportunity to come storming out to oppose the IRA’. His brutal language is partly explained by the relative silence of ‘Catholic Tories’ about the killing of innocent people by the British army. But it wasn’t just middle-class outsiders who were arguing for an end to the violence. A group of Derry peace women confronted members of the Official IRA about Ranger Best – ‘He was killed because he came home to see his mother’ – and three weeks later the Officials called a ceasefire. McCann remembers that

about a week after Ranger Best was shot I argued on a street corner with a lady who had been vigorously supporting the ‘peace campaign’, in the course of which I alleged against her that, ‘I suppose if you knew who did it you would give the names to the police.’ At this she stalked away saying that she had been trying to conduct a sensible discussion and if I was not going to take the matter seriously …

It’s an odd moment in the book, not least because of the way it gestures so strongly towards the suppressed gender politics of the war. McCann’s point seems to be that if this woman was really against violence she would hand in the perpetrators. He doesn’t allow for the possibility that she could be for peace and an end to the violence, but still not want to inform against her community. Arguably, the failure to understand that exact position has been responsible for years of violence. But because he is true to the changing moods in Derry as weeks of conflict turn into months and then years, McCann acknowledges that local attitudes to the paramilitaries within the community were unstable: ‘There was no one in the area willing to sell the Provos out. They were our people. But there were some – not peace women necessarily – who thought that for what we were going to get out of it it was maybe not worth going on.’

The question of whether any of it, after 1969, was worth it, wasn’t something McCann could confront directly in 1974. After the killing of Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie by British soldiers in July 1971, there was a ‘queue’ to join the Provisionals. After internment was introduced, Labour Party members joined the Official IRA, and some Officials joined the Provos. After Bloody Sunday membership of the Provisionals soared. But McCann implies that support for the IRA was a consequence of complete alienation from the British state, rather than of people buying into a republican dream of a united Ireland. The community’s toleration of violence was ultimately a sign of its seriousness. It was a community at war against the state.

In the introduction to this new edition McCann does ask the question: was it worth it, for what we got out of it? He is scathing about Sinn Féin’s rise to respectability since the late 1990s, the tergiversation involved as they rebranded themselves as a party seeking equality for Catholics in Northern Ireland, rather than the united Ireland for which so many had died. He is scornful of their support for the Good Friday Agreement in particular. The Provisional IRA had ‘sneered at’ a similar power-sharing agreement 25 years previously, because it meant accepting equality and civil rights for the nationalist community within the British state. The Northern Ireland Assembly envisaged by the Sunningdale Agreement in 1974 would have replaced the suspended Stormont parliament with a new executive, less dominated by the Ulster Unionists, and headed by an executive made up of representatives from across the communities. A Council of Ireland was proposed, with a consultative role for the Dublin government in Northern Irish affairs, and this was one of the reasons large sections of the unionist population rejected the agreement, fearing that it was a prelude to a united Ireland. But republicans rejected it too, because it meant acknowledging the legitimacy of the Northern Irish state. As McCann puts it, ‘The IRA fought on for a quarter of a century of blood and grief before accepting the Good Friday Agreement – memorably described by the SDLP deputy leader, Seamus Mallon, as “Sunningdale for slow learners”.’

But McCann’s contempt isn’t just for the waste of life. He doesn’t believe the Good Friday Agreement can work, and on this he is being consistent. Although he had finished War and an Irish Town before Sunningdale, the book clearly prophesies its failure. Nothing in his experience suggested that trying to equalise power between two warring communities was going to work. McCann’s Marxist analysis looked for the causes of the Troubles in British imperialism and class warfare, and saw sectarianism as a symptom rather than a cause of violence. The problem with power-sharing, as McCann sees it, was that it institutionalised rather than transcended sectarianism. He has not changed his mind. The Good Friday Agreement has ‘required and formalised sectarianism, now to be characterised by peaceful competition rather than hostile confrontation’. This is a blueprint for deadlock. It might bring an end to the violence of the past, but it offers little hope for a different sort of future. The agreement enshrines a model of politics based on the idea of communal identity, and in effect it not only needs extremes – the two main parties, Sinn Féin and the DUP, represent the most radical sections of their communities – but also that they stay the same. (Every member of the Assembly must designate themselves either nationalist or unionist – no waverers allowed.) The central issue in Northern Ireland is still social deprivation: lack of houses, lack of jobs, the underfunding of schools and the NHS, cuts in welfare. But the politics of the Assembly militates against any of these issues being addressed, even when it is sitting. As it is, the executive has not met since its then deputy leader, Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness, resigned in January 2017 in protest at a financial scandal involving his opposite number in the DUP, Arlene Foster. For the past two years attempts to form a new power-sharing executive have repeatedly foundered on the rock of communalist politics, as disagreements over legislation to protect the Irish language (for example) have taken precedence over the need to do something about hospital waiting lists.

McCann’s pessimism about the Good Friday Agreement may be justified – and the fact that there are now more peace walls dividing the two communities than there were twenty years ago should give us pause. On the other hand, very few people have been killed since 1998. The hope that reduced violence may, in time, bring about a different politics does not seem any more misplaced than McCann’s faith in working-class unity as the solution to the Troubles. Northern Ireland is a ‘post-conflict’ society, as the jargon has it, rather than a society at peace. The politics of communalism make it hard to move on, but it is also hard to go back. The unresolved past poses a threat to political stability. So, for example, proposals for a peace centre at the former Maze prison collapsed in 2013, over fears it would become a ‘shrine’ to IRA terrorism. Debates about who began the killing are off limits, because no one can be seen to have a stronger claim to the past than anyone else. In this context McCann’s messy and contradictory memoir holds out more promise than any official history or commemoration, precisely because of the space it gives to the confusion and ambivalence of those ordinary people who were caught up in the conflict, but were also – like the woman with whom McCann argued in 1972 – able to detach themselves from it.

Lyra McKee, a young journalist, was shot last month during rioting in the Creggan area of Derry that began in the wake of a police raid in search of firearms. According to some, the unrest was orchestrated for the benefit of a TV crew that was in the area to shoot a documentary about hardline republicans. McKee was standing close to a police vehicle when she was shot by a single gunman who was firing towards the small crowd of onlookers. The sniper was reportedly an 18-year-old member of the New IRA, a dissident republican group. Local coverage of the tragedy hasn’t represented this boy as one of McCann’s frustrated and lawless hooligans, but as a young man born after the passing of the Good Friday Agreement, manipulated by bullies and gangsters. Saoradh (‘Liberation’) is the organisation that functions as the public face of the New IRA. Its founders reject the Good Friday Agreement and see themselves as the true inheritors of the unfinished Irish republican struggle, still fighting British imperialism in Ireland. The organisation released a statement claiming that McKee was killed accidentally when ‘a republican volunteer attempted to defend people against the PSNI/RUC’. Currently, the new police force in Northern Ireland (the PSNI) is appealing for information on McKee’s killer. They may not get it. But the appearance of graffiti threatening informers with execution in the days after her death suggests that the New IRA is worried about its levels of support. And no one watching the protest outside Saoradh’s Derry headquarters on 22 April – as McKee’s friends took turns to imprint the walls with bloody hands – could doubt the disgust with which the middle-aged ‘freedom fighters’ standing guard outside the building, arms folded, are regarded by their neighbours.

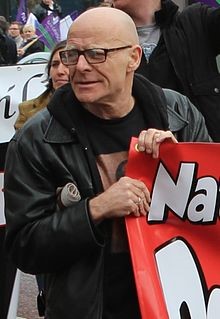

Book Author Eamonn McCann is an Irish politician, journalist, political activist, town councillor from Derry, Northern Ireland, and a former Northern Ireland Assembly member. Along with Bernadette Devlin McCalisky, he was a key leader of Northern Ireland's civil right movement, instrumental in setting up the Bloody Sunday Justice Campaign and co-author of the well-regarded Bloody Sunday in Derry: What Really Happened. His writing has appeared in the Belfast Telegraph, The Irish Times, the Derry Journal, as well as a column in the Dublin-based magazine Hot Press, and is a frequent commentator on the BBC, RTÉ and other broadcast media.

[Essayist Clair Wills is King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at Cambridge (UK).. Her latest book is Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Postwar Britain.]

Spread the word