STANDING ON SLAUSON AVENUE last month, Arianne Edmonds joined Angelenos who gathered along the 25-mile route of rapper Nipsey Hussle’s funeral procession. Thousands of fans thronged sidewalks to raise a fist or a camera toward his hearse as it passed through mostly Black and Latino neighborhoods in South Los Angeles. Even in mourning, they celebrated a local son whose murder only magnified the odds he defied to succeed.

Edmonds is a fifth-generation Los Angeles native. Her family history in the city stretches back to the turn of the 20th century, when Los Angeles’ Black population numbered just 2,000 or so. Those early pioneers included her great-great-grandfather, Jefferson Lewis Edmonds, who founded The Liberator, a newspaper that published from 1900 to 1914 and helped build the city’s Black community. Long before Hussle could become “the street’s voice out West”—before there were many streets here, really—it was JL Edmonds who repped and hyped LA.

Later that day, Arianne Edmonds became teary as Hussle’s music played on the patio of Simply Wholesome, a Black-owned health food shop that’s been around since 1981. As the dipping sun lit the sky an Instagram-friendly pink blush, she looked approvingly at the Black clientele filling nearby tables.

“Now there’s thousands and thousands of us here,” she marvelled. There are more than 800,000 Black Angelenos.

“And Jefferson put out the call. He was like, ‘Come here, because we can have whatever kind of life we want.’”

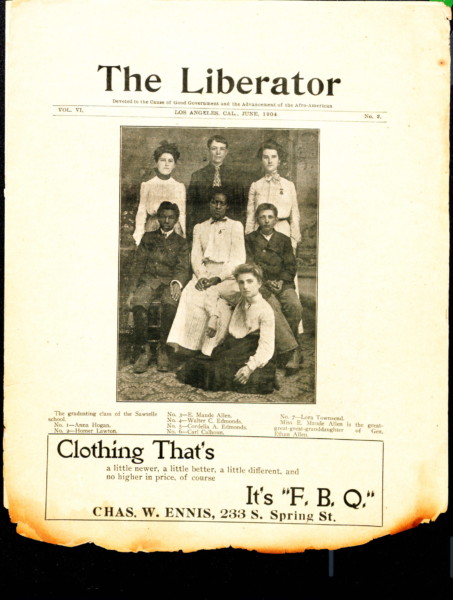

Photograph published in The Liberator, volume 6, issue no. 2, featuring a photo of the 1904 graduating class of Sawtelle School. Courtesy the Edmonds Family Collection | Los Angeles Public Library Special Collections

JL EDMONDS WAS BORN A SLAVE in 1852 in the antebellum South, and lived through the racial violence that erupted after the Civil War. He reached voting age the same year the 15th Amendment gave Black men the right to vote, and faced down mob violence in 1875 to cast a ballot in Mississippi, where he worked as a teacher in Freedmen’s schools.

“He was a civil rights activist at heart and really fought for Black men to be able to vote,” Edmonds says, adding that her ancestor was run out of the state because of that work.

At age 40, Edmonds, along with his wife and nine children, left Mississippi for California, where he continued to advocate for voting rights. In an 1894 letter to the Los Angeles Times, he wrote, “It is the duty of the American people to see that the laws are upheld everywhere in this broad land, to the end that every citizen, whether white or black, may cast one ballot as he may elect and have it counted as cast, whether he lives in Maine or Mississippi. Upon this principle rests our national life.”

An avid reader of abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star, Edmonds undertook newspapering with optimism and a preternatural sense of duty to Black civic life. In 1896, according to his descendants, Edmonds published his first newspaper, The Pasadena Searchlight, of which there is no known surviving archive. Edmonds moved his small press 10 miles southwest to downtown where, in 1900, he launched The Liberator. It ceased publication with his 1914 death.

Alongside poetry and personal ads, Edmonds extolled the virtues of California in his newspaper, at times seeming to speak directly to the Southern Blacks he left behind, promising safety and opportunity beyond any they’d experienced in America. Long before redlining and racial housing covenants limited opportunity for Blacks to buy homes in Los Angeles, Edmonds saw a window of opportunity.

“His desire was to let people know that California, specifically Los Angeles, the opportunity for African-Americans to own their own business, to be entrepreneurs,” Taylor Bythewood-Porter, a curator at the California African American Museum who developed a current exhibit of Edmonds’s work, says. “There was work here for them, that there was opportunity to own their own home, to have land.”

Representation mattered to Edmonds. Under headlines such as “Negroes Who Have Made, And Are Making History,” Edmonds published photos of Black war heroes and business owners, alongside profiles and vignettes. In “Why Negroes Should Own Farms in California,” Edmonds wrote that the state “offers the home seeker two of the chief essentials to success as a farmer… absolute freedom in the enjoyment of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, coupled with the most fertile and productive soil under the sun.”

Edmonds’s newspaper was part of a post-war surge of Black publications. He became a contemporary of other leading Black editors, such as JJ Neimore and Charlotta Bass of The California Eagle, Robert Sengstacke Abbott at The Chicago Defender, and WEB Du Bois of The Crisis magazine. Edmonds played host to Du Bois, who was the first Black Harvard-educated sociologist, when Du Bois visited Los Angeles in 1913. Back in New York, Du Bois wrote, “Los Angeles is wonderful. Nowhere in the United States is the Negro so well and beautifully housed, nor the average efficiency and intelligence in the colored population so high.”

As Black journalist Vernon Jarrett observed more than a century later, Edmonds and his contemporaries in the Black press found success in postbellum America by telling untold stories. Jarrett, who died in 2004, began his career at The Chicago Defender, became the first African American syndicated columnist for the Chicago Tribune, and was a founder of the National Association of Black Journalists. In a 1999 documentary, he said:

Black people didn’t exist in the other papers. We were neither born, we didn’t get married, we didn’t die, we didn’t fight in any wars, we never participated in anything of a scientific achievement. We were truly invisible unless we committed a crime. But in the Black press, the Negro press, we did get married. They showed us our babies when born. They showed us graduating. They showed our PhDs.”

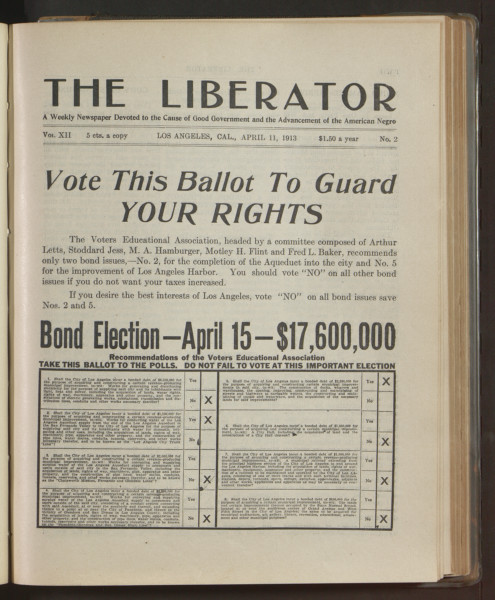

The Liberator, from April 11, 1913. Courtesy the Los Angeles Public Library Special Collections | California Revealed

WHILE EDMONDS PROMOTED CALIFORNIA to outsiders, he also worked to make it better for Blacks already living here by telling untold stories of racial discrimination. It was a revolutionary act when The Liberator published voting ballots and instructions on how to vote in its pages.

Edmonds was fearless in keeping white politicians accountable to the early promise of freedom and equality. During the 1913 LA mayoral election, Edmonds took up the cause of economic equality for Blacks, openly opposing candidate John Shenk, the city attorney who argued LA business owners had a right to charge Black people more for goods and services. The Liberatordecried Shenk’s blunt racism in an ongoing campaign. When Shenk lost by a narrow margin, Edmonds credited the Black community’s ballot influence.

“He would often uncover these untold stories of racial discrimination and let people know, These are what the politicians are doing,” Bythewood-Porter says. Arianne Edmonds says her ancestor was “holding our local officials accountable.”

Down the road, the Los Angeles Times was doing similar promotion of California’s economic opportunity and perfect weather, touting the city as “America’s Great White Spot”— apparently a description of the city’s lack of crime and unions. As a prominent member of the Black community, Edmonds was occasionally commissioned by the Times to write. On President’s Day in 1909, Edmonds wrote a column describing what it felt like to be a slave as a young boy, and to experience emancipation.

“What effect has the negro’s presence in this country had upon its history? Let’s see: If we erase from American history the pages that the negro’s presence caused to be written, it would be a short, uninteresting story,” he wrote.

Looking back, his great-great-granddaughter says Edmonds seemed chummy with white newspaper editors at the Timesuntil Edmonds criticized coverage of a murder case that he felt framed a Black man.

“He was referred to as ‘J. L. Edmonds, Editor of the Liberator’ when he stayed in his lane,” Arianne Edmonds says. “But as soon as he spoke up, he became ‘Edmonds the negro pamphleteer always looking for a political hand out.’”

The Times ran Edmonds’ obituary on January 9, 1914. It ran in the “Local News in Brief” column, alongside banal meeting notices for Bible classes and social clubs. Its single line read: “J.L. Edmonds, editor of the Los Angeles Liberator, died Wednesday night at his home in Sawtelle.” There was no mention of Edmonds’ age or family members, no description of his birth into Southern slavery or his relocation to the West Coast as a free man.

He was eulogized lovingly by the Black press. In San Francisco’s Western Outlook, Edmonds’ obituary began:

The death of J.L. Edmonds, editor of the Los Angeles Liberator, removes from the scene of action one of the most forceful writers of the race on the coast. He was a man who stood up for his convictions, and seemed to fear nothing. He believed in the right and stood up for the same and was a staunch advocate of manhood rights for his race…

“Towards the end of his life a lot of his legacy was being swept away,” says Arianne Edmonds. “I think he was heartbroken. His reputation tarnished. All of his work was boiled down to one sentence.”

Arianne Edmonds with her father, Paul Edmonds. Photo by Shaya Tayefe Mohajer.

EDMONDS HIMSELF HAD COPIES of The Liberator bound. The tomes were handed down, generation after generation, until they reached Arianne and her father, Paul Edmonds.

Growing up in west Los Angeles in the ’60s and ’70s, Paul Edmonds had a picture of his great-grandfather on his wall—mostly because his mother had put it there. Now 60, Paul Edmonds tugs at his baseball cap shyly when he admits he didn’t know much about the legendary Black newspaper editor. When he inherited bound copies of The Liberator, he tucked them into a safe, imagining he might ask his daughter to help with them someday. Arianne Edmonds had gone to the East Coast to attend college and to chase her dreams for a while, but those dreams eventually—and quite literally—turned her towards home. “Jefferson kept coming to me in my dreams, telling me to move back home,” she says. “I left and haven’t looked back.” That was more than a decade ago.

In Los Angeles, Arianne Edmonds studied her ancestor’s archives and looked for ways to showcase his work. Those efforts have recently come to fruition. In March, the California African American Museum launched its exhibit dedicated to The Liberator, which will run through September 8. Later this year, the Los Angeles Public Library will release a digitized archive of every issue of the newspaper. Lesson plans are in the works for Los Angeles public schools to teach about The Liberator and the city’s early Black civic leaders.

“We want scholars and students and artists to have access to this,” Arianne Edmonds says. “I think we also needed to wait for the right time for, I think, our world, our society, our community to be ready to receive these stories.”

Shaya Tayefe Mohajer teaches journalism at the University of Southern California and works as a freelance journalist in Los Angeles. Previously, she was the news editor for TakePart.com and a reporter for The Associated Press. She is a graduate of New York University's masters program in journalism. Follow her on Twitter @Shaya_in_LA.

Has America ever needed a media watchdog more than now? Help by joining CJR today.

Spread the word