Over the past fifty years, cycles of disinvestment and aggressive reinvestment in urban real estate markets, stagnating wages, and neoliberal shifts in federal housing policy have created a complex housing system that is fueled by debt and fails to serve a large swath of the population. Housing advocates continually struggle with logistical questions about the longevity and depth of affordability in affordable housing and structural questions about the roles of the market and the state in the provision of housing.

It is difficult to pin down the functional definition of what a house is in America: shelter, sanctuary, a societal building block, a wealth building mechanism, and/or a commodity. What is clear, from high rent burdens, widespread evictions, and growing homelessness, is that existing tools are not working.

Over the past few years, the community land trust (CLT) model has been increasingly promoted as a solution by affordable housing advocates of many kinds, from anti-gentrification and tenants advocates to traditional community development organizations to large philanthropic institutions like the Ford Foundation and the Federal Reserve. The CLT model is highly flexible, and has huge potential for addressing the affordable housing crisis in America today.

What Is a CLT?

At its core, a CLT is an entity organized to maintain the ownership of land for a specific, community-oriented purpose, forever. It is designed to be a nontraditional form of property ownership, where the ownership of land is separated from the ownership of property.

The relationship between the entity that owns the land and the entity that builds and operates the buildings that are on the land are defined by what’s called a “ground lease.” In the United States, ground leases are most commonly used in the development of commercial real estate. They give the developer of a building strong control over what happens to a property for a long period of time (for as long as ninety-nine years), while allowing the land owner to retain the rights to the land itself. In real estate terms, a ground lease allows a developer to substantially lower their front-end costs by avoiding paying for land.

In Marxist terms, a ground lease creates a legally acceptable framework for separating the use value (in this case, the use of a building to actually house someone) of a property from its commodity value (the building’s generation of profits for a seller or landlord), creating a pathway for its decommodification. A CLT takes the ground lease model and injects a social mission: the entity that owns the land holds it in trust for a designated use — like the provision of below-market rate housing or the protection of green space — in perpetuity.

Governance and Participation

To formalize and define “community,” CLTs often incorporate a unique governance structure, where the entity that owns the land is overseen by a board that includes some combination of people who live/use the buildings on CLT land: the surrounding “community” and representative “experts” and/or members of the public.

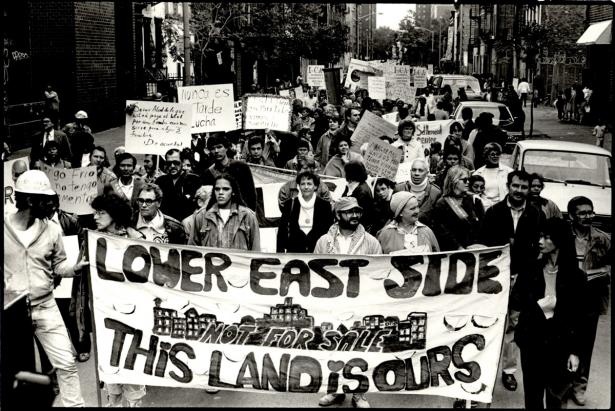

Ideally, a CLT ownership structure both puts into practice ideas about collective ownership of urban land and diffuses power between people who directly benefit from the CLT and the broader community indirectly impacted by the CLT. Or, as Howard Brandstein, who helped incorporate a CLT on New York City’s Lower East Side in the 1980s, put it, “the land trust was a means for neighborhood residents to withstand the challenge of market forces entering the Lower East Side by bridging the separation between ownership as an expression of self-interest, on the one hand, and community empowerment on the other.”

In practice, the levels of resident-driven control among CLTs, and the extent to which residents are ideologically committed to decommodifying housing, vary greatly. Some CLTs, especially those rising out of neighborhood-based struggles, explicitly incorporate horizontal governance, consensus-based decision making. Others are centrally driven and only nominally incorporate residents into the decision making process.

Pitfalls of Model Flexibility Permanent Stewardship

Part of the CLT model’s strength is its flexibility — there is not a hard definition of what a CLT should look like exactly, beyond a ground lease driven relationship between an entity that holds land in trust for a common good and the people who use the land.

The sale of buildings on CLT land is governed by a resale formula outlined in the renewable, usually ninety-nine-year, ground lease, which gives the CLT the first right of purchase, allowing it to control the value of the properties themselves and to enforce affordability restrictions and income targeting. Organizers of the CLT can tailor the ownership structure within the buildings, income-targeting, service provision, and rent restrictions to local needs.

Buildings on CLT-owned land may include owner-occupied single-family homes, rental buildings, self-managed cooperatives (limited equity and otherwise) or mutual housing associations, commercial, manufacturing, and office spaces, farms, and/or green spaces. This gives the organizers of a CLTs wide latitude to solve local problems, whether they are racist segregation, environmental preservation, or displacement as a result of gentrification.

This flexibility, mixed with the responsibility of permanent stewardship, creates the possibility for both co-optation and mission slippage, especially as CLTs engage in real estate development to achieve community-driven goals. Dana Hawkins-Simons and Miriam Axel-Lute point to a common criticism of all community developers: “ . . . reliance on accessing public affordable housing funds has turned community developers away from their civil rights roots and muted their voices on controversial issues in their neighborhoods and cities.”

And because CLTs (even those that are resident-controlled), exist outside the public sphere, they do not operate under a clearly stated public mandate. Given the long timeline (forever!) of CLT stewardship responsibilities, the danger of eventual loss of community-orientation, especially as the CLT undertakes development, is there.

CLT Landscape Today

Despite a strong association with affordable urban housing, community land trusts in the United States begun as a rural experiment in securing land rights for African-American farmers. New Communities, Inc. (NCI) was organized by veterans of the Albany Movement, the first mass organizing effort in the 1960s to fully desegregate a Southern city.

After witnessing evictions and job losses as repercussion for anti-segregation organizing, movement organizers like Charles Sherrod of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) — who would later become president of New Communities — came to believe that “the only way African Americans in the Deep South would ever have the independence and security to stand up for their rights — and not be punished for doing so — was to own the land themselves.” Incorporated in the late 1960s, New Communities purchased five-thousand acres, to be held in trust, and developed a ground lease system, which allowed for both individual homesteads organized in two residential communities and cooperative farms.

Like many urban CLTs that came later, NCI was a culmination of long term organizing against a spatially-enforced system of disenfranchisement. Since the denial of property rights has been one of the key methods for reinforcing white supremacy in the United States, civil rights organizers developed a model that centered around claiming power through land that also went beyond the traditionally American system of individual ownership.

CLTs in Disinvested Markets

The rural CLT model made its way to urban areas in the United States in the 1980s, proving to be a good fit for a disinvested post-fiscal crisis landscape. Many formally redlined neighborhoods in American cities were awash with public, tax foreclosed properties and sites of intensive local organizing.

In some cases, like the CLTs that emerged on the Lower East Side, organizers were noticing early signs of gentrification and land speculation, which resulted in the loss of affordable housing — a problem that the CLT structure could help address. In others, like the Sawmill CLT in Albuquerque, the focus was on environmental justice, with a CLT as a culmination of a broader effort among residents to address a public health issues in their neighborhood.

These CLTs were often organized alongside other neighborhood stabilizing efforts, from community development corporations to homesteading and squatting efforts. In an extensive study of CLTs and Mutual Housing Associations, John Krinsky and Sarah Hovde wrote that CLTs were perceived to be able to resolve problems and conflicts inherent in the co-op model on the one hand, and the nonprofit rental model on the other.” Unlike other affordable housing efforts during this era, CLT organizers often took a longer, less market-oriented view.

For example, affordable rental housing developed with low income housing tax credits by community development corporations before 1980s had fifteen-year affordability agreements, while CLTs created a framework for perpetual affordability. But most disinvested cities pursued strategies that returned public land to the private market as quickly as possible, making CLTs minor players in the urban redevelopment process.

A market-based logic still dominates in disinvested communities today. Cities devastated by a racially and economically motivated policy and private lending practices — from redlining to subprime mortgages — search for ways to attract investment, often by giving away land. Today, unlike the 1980s, there has been a rising reliance on land banks in cities like Detroit, as opposed to tax foreclosure auctions which are rigged heavily toward developers, to more thoughtfully channel the redistribution of public land. But most continue to focus on transferring land to professional developers or promoting homeownership with time-limited affordability requirements. Similarly, many CLTs today orient their language and marketing around affordable homeownership and foreclosure prevention, rather than broad land reform.

At the same time, local interest in CLTs as a tool to address broader land-based social justice issues remains. For example, the Detroit People’s Platform — a broad coalition of social justice organizations, activists, and residents that emerged after the city’s bankruptcy — sees CLTs as “a potential alternative to profit-driven development and a means to resist the continued movement of public-owned commons into the private sector.” And organizers and residents are increasingly seeing CLTs as a way to engage in participatory neighborhood planning in disinvested neighborhoods: the model is suited for this role because CLTs are geographically targeted and could operate on a multi-block scale.

This was the model employed by Dudley Neighbors, Incorporated(DNI) in Boston, which led to a CLT with “225 new affordable homes, a 10,000 square foot community greenhouse, urban farm, a playground, gardens, and other amenities of a thriving urban village.” T.R.U.S.T. South LA is undertaking a similar larger scale planning effort in Los Angeles.

The model creates a framework for residents to understand and challenge neighborhood market forces that often stay hidden. For example, the New Columbia Community Land Trust in Washington, DC, helped residents faced with displacement ask why the value of public amenities, like a subway, should accrue to private real estate owners at the expense of low- and moderate-income tenants.”

CLTs in Expensive Markets

Most recently, CLTs have begun to gain traction as an affordability preservation tool in expensive land markets. Older land trusts like Cooper Square CLT on the Lower East Side and DNI have seen the neighborhoods around them transform as aggressive reinvestment has driven up rents and displaced long term tenants. In Seattle, San Francisco, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and other cities, both grassroots organizations and established CDCs have looked to CLTs as an anti-gentrification tool.

Disinvestment and aggressive reinvestment are part of the same problem faced by urban neighborhoods, especially in neighborhoods of color. While existing CLTs do soften the impact of this cycle, groups starting new CLTs in gentrifying neighborhoods often find it difficult to overcome the main problem they are trying to address: skyrocketing land costs as a result of speculation. In a 2015 Next Cityarticle, Jake Blumgart wrote:

In Seattle, it took Homestead Community Land Trust ten years to bring its first house into its portfolio and twenty-two years after its founding, the trust has not been able to obtain land on the cheap from the city. Though the trust was founded in 1992 to preserve affordable housing in the Central District, once Seattle’s premiere African-American neighborhood, today only six of their 191 homes are located in the neighborhood because of the high cost of land there.

In high cost land markets, CLTs — like the Chinatown Community Land Trust in Boston — are generally unable to compete with private capital in the open market. And even as aggressive investment displaces residents, cities often continue to pursue market-oriented strategies for public land.

For example, in New York City — with the hyper financialization of affordable housing development has resulted in predatory equity driven tenant displacement in neighborhoods where the city could not give land fast enough in the 1980s — nonprofit affordable housing developers overall have long complained of being sidelined in favor of profit-oriented developers. While New York City is not awash with tax foreclosed property, the city continues to include public land in packages for income-targeted housing development.

Local CLT-oriented efforts, including an alternative plan for a city-owned armory in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and a redevelopment of a public library in Inwood, Manhattan face uphill battles — “the thresholds for the experience and financial heft bidders must bring to the table” are out of reach for sophisticated and well-established CDCs, much less a new grassroots group formed to address a local neighborhood needs.

Implementation and Scaling

Obstacles to land acquisition and municipal polices that rely on market-based solutions have limited the impact of CLTs on American cities. Even though there are approximately 280 CLTs in the United States today, many have not secured land to steward. CLTs face many of the same obstacles as smaller community-oriented developers. Development is expensive, and hard to do without strong municipal support.

The CLT with the largest influence on the housing market where it’s located is The Champlain Housing Trust, controlling 7.6 percent of the Burlington’s housing stock. When it launched in 1984, the land trust received substantial support from then-mayor Bernie Sanders, including a $200,000 seed grant, a pension fund loan, and, importantly for its longevity, ongoing funding through the Burlington Housing Trust Fund funded by a small property tax increase. The land trust also received funding from a local bank (likely, to meet its Community Reinvestment Act requirements) and HUD.

To gain municipal support, CLT organizers need to engage in policy advocacy, in tandem with intersecting housing movements, including both policies that are immediately beneficial for CLT development and broadly beneficial for low-income people: housing trust funds that provide ongoing rental assistance to low-income tenants, tax breaks for permanent low-rent housing, rent regulation, anti-eviction programs, and increased support for public housing. The New York City Community Land Initiative in New York City, for example, was initiated by multiple local organizations, including Picture the Homeless, a homeless-led organization that advocates for better homelessness resource spending.

More broadly, CLTs — along with other forms of housing that minimize speculation, including rent control and public housing — should be viewed as one of the means for creating a less exploitative housing system in the United States. As argued by David Madden and Peter Marcuse in In Defense of Housing, urban real estate are central drivers of the market. Models that help to de-commodify housing can be transformative, if applied together.

At the same time, Robert Swann, who helped launch New Communities, Inc. and the Institute for Community Economics, cautioned against a “housing only” focus among CLT organizers, positioning the model as a broader means for reducing speculative profit through land reform. CLTs should also seek partnerships within the growing “solidarity economy” sector to achieve scale.

Evan Casper-Futterman wrote about two umbrella organizations the Philadelphia Area Cooperative Alliance (PACA) and the Cooperative Economics Alliance of New York City (CEANYC), which “aim to unite worker cooperatives and housing cooperatives and their sectoral networks with food cooperatives and other consumer and financial cooperatives such as local cooperative investment funds, community development credit unions and community-based organizations working on issues of labor, immigrant, racial, and economic (in)justice.”

Of the CLTs that have the strongest internal cohesion are those that have developed mechanisms for continual resident participation and are responsive to changes within the organization as it ages. CLTs that are born out of local organizing are likely to experience a level of internal tension, especially if the organization directly undertakes new housing development. Harry Smith, director of Dudley Neighbors, Inc. described the CLT’s foray into development as traumatic, because “it took so much time. It distracted DSNI from its core functions. It’s important to be explicit: If you do development work, it will take away time from organizing.” Some CLTs do not undertake development work directly for this reason.

Even if a CLT is not rapidly expanding, there is always a continuing need for ongoing education, engagement, and organizing, especially as the first generation of residents ages out. In their review of twenty CLTs in the 1990s, Krinsky and Hovde found that the presence of organizers on staff helped drive resident participation. Organizing and engagement — not just of residents but of the community as whole (however it is defined by the CLT), including prospective residents — is necessary to avoid the CLT becoming a back door entry to privatization, especially in instances where public land is involved. Further, an enforceable and iron clad legal framework is equally necessary, for the same reason.

Today, as during the Civil Rights era in the late 1960s or neighborhood based organizing in the 1980s, CLTs continue to reappear in movement contexts. The Movement for Black Lives calls for a coordinated review of “ . . . tax credits, insurance systems and budgets concerning various elements of development (e.g., housing, schools, community, highways, etc.) and align around the goal of fair development with an emphasis on community land trusts, cooperatives, and community control.” Similarly, community land trusts are often a feature of “radical municipalist” movements, most prominently in the United States as part of Cooperation Jackson, an effort to organize and empower “the structurally under and unemployed sectors of the working class, particularly from black and Latino communities, to build worker organized and owned cooperatives will be a catalyst for the democratization of our economy and society overall.” CLTs are not a silver bullet. But they provide a framework for organizing efforts to reimagine their neighborhoods and cities as more than just places.

[Oksana Mironova writes about cities, housing, and public space. Her writings can be found on her website oksana.nyc and on Twitter.]

The new issue of Jacobin is out now, ON THE HOUSING CRISIS AND CAPITALISM, IS OUT NOW. GET A DISCOUNTED SUBSCRIPTION TODAY.

CATALYST, A NEW JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY JACOBIN, IS OUT NOW.

Spread the word