After World War I, job competition and housing shortages fueled race riots across the United States. A major race riot tore Chicago apart in the summer of 1919. Gary, however, did not experience any race-based uprising. In the midst of these national crises over race, on September 23, 1919, 350,000 iron and steel workers went out on the largest national strike recorded up to that time in the U.S. Strikers were demanding an 8-hour day and union recognition.

Judge Elbert Gary headed up Carnegie Illinois Steel (later U.S. Steel) and used the racial tensions in the nation to provoke hostilities and then crush the steel strike. In many steel towns on the East coast, racial hostilities erupted during the strike, because Judge Gary had brought 30,000 Southern Blacks up North to work as scabs. The mills in the Midwest were newer, required less skilled labor, and employed large numbers of first generation immigrants. The Eastern mills did not hire blacks, but in the Midwest, close to 3,000 black workers had been hired during the World War I.

Elbert Gary’s strategy to divide the workforce along racial lines did not work in Gary. Strong inter-racial solidarity, built intentionally to avoid the conflicts developing elsewhere, prevented trouble. Many histories of the Region, however, argued that racial hostilities were involved in ending the strike in the Calumet Region. This was not the case.

This article explains why race riots and racial hostilities did not emerge in Gary, and also why so many—up to the present—believed that race ended the strike in the Calumet Region.

Part I: Pioneer Freedom Fighters

Two black leaders of the NW Indiana Allied Iron and Steel Council, Louis H. Caldwell and C.D. Elston made the difference. The Allied Council was the coordinating and organizing body for the steel strike. With the support from strike organizers nationally, Caldwell and Elston led a systematic effort to build solidarity among the workers. They organized black workers separately at first and then spoke at every meeting and gathering of iron and steel men in the Region.

Louis H. Caldwell identified himself as “a new Negro.” Born in Copiah County, Mississippi, young Louis was the first in his family of former slaves to attend college, He graduated in 1903 and became a Pullman Porter. Pullman porters learned about the oppressive race and class hierarchies as they traveled the country, serving the ultra rich in Pullman’s luxury train cars.

Caldwell soon moved to Chicago, and, while working at Hart, Shaffner and Marx, put himself though law school. In 1915 Caldwell moved to Gary, found a job at American Sheet and Tin Plate Company, while he awaited certification as an attorney.

Sheet and Tin employed only 19 African Americans at that time. Caldwell was a founding member and leader of the Gary NAACP. In 1917, he published a letter in The Crisis, NAACP’s newspaper, condemning black support for the Republican administration that controlled Gary. “All they talk about is Lincoln,” he wrote. “They must learn they are dealing with a new Negro who wants representation and justice before the law.”

While working at Sheet and Tin, Caldwell got to know the life-threatening conditions facing steel workers, especially black steel workers. They held the dirtiest, most dangerous jobs on coke batteries and in furnaces. They worked 7 days a week, 12 hours a day and, every other week, they worked a 24-hour shift. The injury and death rates in the mills during World War I matched the deaths of U.S. soldiers on the battlefield.

When Caldwell became an attorney—there were only 3 black lawyers in Gary at the time—he represented black iron and steel workers and their families against the corporations. He was an ardent supporter of unions and was one of the first to join the campaign to unionize the industry in 1919.

Caldwell was not alone. Another black steelworker who worked at the Carnegie Illinois’s big mill in Gary (U.S. Steel), C. D. Elston, quit his job in order to join the Allied Iron and Steel Council. Unfortunately we know little about Elston, apart from his speeches, captured in local news reports.

Beginning in February 1919, these two men spoke on the importance of solidarity, unity and respect for black rights at every meeting, march and rally. On February 2, 1919, the Gary Evening Post reported a scheduled meeting at Turner Hall for “Gary colored workers.”

From February to September 23rd when the strike began, special meetings for “colored iron and steel workers,” Mexican, Polish, and Serbian workers, were held across the city. Caldwell and Elston spoke at almost every one.

At Gary’s first Labor Day celebration in 1919, C.D. Elston directed his words to black workers in the crowd. Holding up a piece of paper, he announced: “I got a letter here for you. It is from Judge Gary. He gave me two he liked me so well.” In response to shouts and laughter, Elston added: “He says he will take care of us, but if he did, we would all be in hell.” Echoing the optimism of the moment, Elston finished: “The color line has been obliterated and we are harmoniously recognized.”

Then Caldwell stepped forward. “Whether the strike be won or lost, I want to ask every man to conduct himself with due respect for civilization and humanity.” As reported by the Daily Tribune, “With hats thrown in the air and the crowd cheering him, Attorney L. H. Caldwell, colored, of this city, delivered one of the most forcible speeches ever heard on the race question in this locality. His speech was actually an educational lecture.”

Caldwell explained to the crowd: “One race oppressed blocks the growth and advance of another. For hundreds of years the negroes of this country have been held inferior and I defy any man or body or corporation that will use my people for a cause to create a race riot, by pitting one race against another . . . I want to say right now,” Caldwell concluded, “that the colored people will not and dare not be made goats of this strike. The negro cannot rise with the white people holding them down!”

Part II Background- The City & the Mills

At the turn of the 20th century, most unions excluded blacks and blocked them from jobs. This had been the case in the iron and steel industries. The unions at that time were for skilled trades workers who were primarily white and native-born. Most often, the only way black workers could get a job in industry was by crossing a picket line during a strike. This led to the labeling of blacks as “a race of scabs.” Black strike leaders Louis Caldwell and C.D. Elston made sure that would not happen in Gary.

NW Indiana had the newest mills in the country, requiring fewer skilled tradesmen and more unskilled labor. In the mills on the East Coast, blacks were not hired at all, even for the dirty jobs. In the Midwest, close to fifty nationalities of immigrants had settled in NW Indiana; they had not yet learned the racist practices of the land. In Gary below the Wabash tracks, immigrants and blacks often lived in the same neighborhoods, crowded into tenements and ramshackle housing. While social integration was rare due to language and cultural issues, immigrants and blacks often worked in the same mill departments.

When immigration was cut off during World War I, more blacks moved north for a job in steel. Gary’s mills, in particular, hired increasing numbers of blacks. Wartime labor shortages opened Gary’s door to rural and working-class Southern blacks. They settled in the area between 15th and 25th Avenues where local real estate interests had thrown up housing without streets, electricity, indoor plumbing or any form of sanitation. This area became increasingly black and was known as “the Patch.” There were 2.699 black workers in Gary’s Carnegie Illinois (U.S. Steel) mills in 1919.

Elbert Gary hated unions. He was the first person to articulate the slogan of “right to work” as an anti-union tactic, arguing that unions deprived workers of a job if they did not join the union. To break the 1919 strike at its beginning, Elbert Gary planned to incite racial hostilities. He ordered 30,000 black workers be brought up from the South to take jobs in the mills on the East coast. In the Calumet Region, a few blacks were brought into the mills on ore boats. For the East Chicago mills, recruiters went to Mexico. But 85% of the workforce in the Region joined the strike, preventing any production.

Elbert Gary’s strategy failed in NW Indiana, due to the far-sighted organizing in the Region to unite workers across racial divisions. As described in Part I, special meetings and continuous educational speeches had united workers. Most of the black workers already in the mills went out on September 23rd in strong support of the strike. Mass rallies were held daily, where black leaders Louis Caldwell and C.D. Elston addressed the multiracial crowd.

Despite rumors of Bolshevik intervention, racial hostilities and violence, everything was peaceful in the Region.

The City’s Evening Post sent reporters into the mills where they noted no smoke, no production and very few workers. “Beyond the furnaces, we came upon three men pitching horseshoes and encountered three Negroes carrying cots.” Blacks brought in from the South slept in the mill. Near the idled blast furnaces, “five Negroes were stretched out on the ground, sunning themselves.” The company claimed that over 35% of the workforce crossed the line, but the company’s own records reported less than 15%. On October 3, 1919 another reporter counted only 350 scabs entering the mill.

Judge Elbert Gary was desperate to break the strike in the Calumet Region. He was a powerful man backed by powerful interests, able to manipulate news reports and local police forces. State Militia had already been brought into Hammond to put down an earlier strike on September 9, 1919 at Standard Steel Car. Military Intelligence spies were also active in the Region. Their very biased Reports (Military Intelligence Division Papers) claimed that Bolshevik infiltrators and race-baiting were the central challenge in the Region. Neither was true.

One Report claimed: “Many of the strikers are expressing themselves in no uncertain terms concerning the Negro residents of the town. There is quite a large Negro population and many of these failed to walk out with the whites. Talk of race rioting jumped today and threats to kill all the Negroes and wreck their homes were being made. Police authorities and the sheriff’s office feel that this is the most important part of the situation at present.”

Nothing in the press or union papers, nothing in first or second-hand accounts gave any credence to these allegations. Black strike leader Louis Caldwell, however, was very aware of Elbert Gary’s efforts to incite trouble. On September 26th, 1919, at a mass rally Caldwell advised the strikers against violence, declaring that that would be the greatest blow to their cause. Caldwell blamed the steel mill officials for rumors. When the mill officials saw defeat facing them, he explained, they gathered the professional and business men of the city into the “Loyal American League,” a racist, anti-immigrant tool of the corporation.

Caldwell alerted workers “to know their enemies” and to realize that the company had sent spies into the union, and that some of the men wearing union badges were Elbert Gary’s undercover spies. “They have even sent agents to some of our speakers, warning them to be careful of their speech. Here is one mouth,” Caldwell stressed, “they can never close until the lips are sealed in death.”

Part III “Bayonets Walked the Street”

As recently as February 1993, the Gary Post Tribune referred to the 1919 steel strike as the event “that pitted whites against blacks.” Many historians of the strike and of Gary have echoed this view, claiming that black scabbing was a major demoralizing factor, and that the strike in Gary ended because of a race riot.

Where did these stories come from? Just as happens today, company propaganda spread during and after the strike entered into history books, as did the lies created by the military in their Military Intelligence Reports. In addition, most histories focused on the strike on the East Coast where the majority of mills were located. Since 30,000 blacks were brought North to scab in the East, many assumed that equal numbers entered the mills in the Midwest.

A handful of Blacks from Elbert Gary’s Alabama mills were brought into the Gary plants on ore boats. These men never left the mills during the strike. According to the Interchurch Report on the Steel Strike (1920), small numbers of blacks were rotated from one mill to another to incite hostilities. An Evening Post story recounted how the company had offered $5 to blacks if they scabbed, but that the majority had taken the money and left.

It was certainly true that after the strike was crushed, supervisors in the local mills kept repeating to the white workers: “It was the colored that broke the strike.” This was not even true in the East where the main scab force were the skilled native-born tradesmen who were essential to restarting production.

The event that triggered martial law and brought in Federal troops happened on October 4, 1919. On Friday evening October 3rd, over 200 black workers gathered for a mass rally at Croatian Hall. Spanish-speaking iron and steel workers were meeting at Turner Hall. The next morning at Buffington Harbor there was a massive rally. Speakers praised the racial unity and peacefulness of the strike at all three gatherings. So what happened??

Every morning picketers gathered on Broadway at the railroad tracks. The electric trolley cars taking scabs into the mill passed by, allowing strikers to talk through the windows or board the trolley to persuade scabs not to work. On that day, October 4, 1919, South Shore railroad trains were passing, and forced the trolley to stop. That allowed strikers to talk with scabs, and also to pull the trolley’s electric wires off their track so the car would be stuck there.

At the same time, strike supporters were leaving a rally at Buffington Harbor, swelling the number of strikers. Fearful that arguments might flare up into conflict, a leader of the YMCA stepped up on the trolley’s stair to warn against violence. He was hit by a brick; no one knew for sure who threw it. A scuffle ensued but ended within minutes, as union organizers put a stop to the conflict. The police arrived shortly after, and according to the Gary Post Tribune, thanked the union for its quick work. The Mayor also praised the union men for their efforts. Minutes later a rainstorm hit, and the crowd dispersed.

The next day, the anti-union Daily Tribune reported a race riot, claiming that the scabs on the trolley were black, and that a major riot had broken out. A first-hand observer, Johnnie Mayerick—he later became the first president of USWA 1014 at Gary Works—was there bringing water to the strikers. His father was one of them. Mayerick explained in an interview with me that Blacks lived near the mill and were never on those trolleys, that it was immigrants inside and outside arguing with each other. Descriptions in the Post Tribune confirmed his observations. Several accounts said that “it was ethnics on the trolley.”

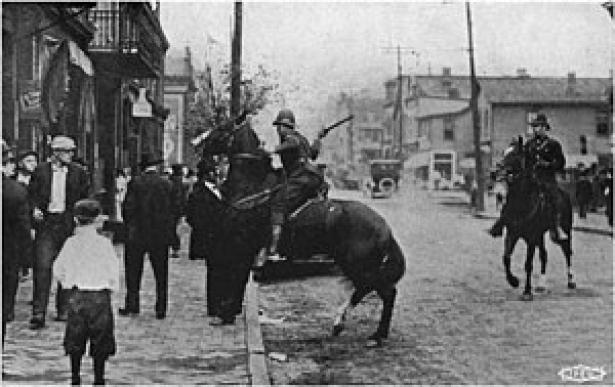

The racialization of this fleeting event gave Elbert Gary what he had been waiting for, a chance to crush the strike. The morning of October 5th, the Mayor was singing a different tune about the incident. He declared martial law, prohibited all public rallies and pickets, called on seven units of the Indiana State Militia, and then Federal Troops under the command of General Leonard Wood.

Two days later, the Evening Post continued to report that Chief of Police Forbis and Mayor Hodges “were well pleased with the fine spirit shown by the citizens of Gary and the strike officials who aided the police…Race trouble did not enter into it and no race trouble is feared by the officials.” In contrast, on October 17th, the Military Intelligence Reports claimed to quote an informant who blamed the incident on black scabs on the trolley. “The colored men [on the trolley] showed fight…and the trouble was on.”

Generations of historians picked up this racialized story. Except for the Military Intelligence Report, there is no other primary source that confirms it. So why did the Post Tribune in 1993 refer to the 1919 strike as the moment that “pitted whites against blacks”?

Part IV: How Can We Learn from History?

“You have to learn from history” is a common piece of advice. But whose history? Written by whom? Towards what end?

The 1919 steel strike in Gary provides an important lesson on the challenge of “learning from history.” In truth, we have to question the history we read, because those who own the corporations and the media tell only their side of the story. Workers, communities of color, the majority of those who lived and suffered through the events rarely have the means to tell their stories. The victors almost always find a way to justify their actions and blame the victims. Finding original sources that include the voices of the people is sometimes impossible.

Even after martial law was declared and rallies prohibited in Gary in October 1919, strikers did not give up the fight. A march of a thousand strikers led by black WW I veterans in uniform walked up Broadway on October 5th to the mill entrance. The Mayor then declared that anyone in uniform that was not part of the occupying military force would be arrested. To get around the order preventing strikers from picketing, Gary women took over the picket line, but to no avail. The repression was powerful, and the strike was doomed.

Yet it was not without positive results, because in the 1920s, while mill supervisors were blaming black scabs for the defeat of the strike, black and white workers began organizing secret locals of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers in every mill in the Region.

In 1920, right after the strike, WWI veteran George Kimbley went to work at Gary Sheet and Tin and was an early recruit to the Steelworker Organizing Committee. He became the first black union staff rep in the Region. Black men like William Young hired in at Inland in May 1922, and then joined the Amalgamated Union in 1926. He became the first black griever and later the first black chairman of a grievance committee. Johnny Howard, whose father went into Gary Works as a scab, immediately sided with the union when he snagged a job in 1935. Curtis Strong organized the first black caucus in steel in 1943 in the coke plant, and became a leader of the National Ad Hoc Committee of Black Steelworkers in the 1960s.

Since 1919 Gary has had a tradition of interracial organizing while also being a center for black movements and black power activism.

Another important contextual issue in learning from history requires knowing who wrote the history and when. For example, historian David Brody wrote his excellent study of the 1919 steel strike, Labor in Crisis, at the close of the McCarthy red-baiting period in this country. He focused on issues of red-baiting because the strike leader, William Z. Foster, a radical, had became a Communist a few years later. Brody glossed over the role of African Americans apart from scabbing.

When Brody wrote his book very little had been written about Black workers. It was not until the 1960s that black labor historians emerged and began to study and correct U.S. labor history to include the positive roles of African Americans. It matters not only who wrote the history but also when it was written.

The idea that there are “two-sides to every story” is also misleading, because there are always multiple perspectives and interpretations, especially when it comes to African American history. I wrote a book based on oral histories with black steelworkers in Northwest Indiana. I was aware that black workers filtered what they told me because of who I am, so I know my accounts are subjective. I did a lot of archival research that helped anchor my stories, and I had each person I wrote about read what I wrote to correct the text. Still, history is never fully objective.

It is always important to keep in mind the structure of power in this country, the systemic, institutionalized nature of racism and white supremacy, and the incredible profitability for corporations of keeping “whites pitted against blacks.” Not all who write history take these factors into account.

The 1919 strike failed in its main objectives: union recognition and an eight-hour day. The education and organizing had long-term effects, however. In the 1920s, the 12-hour day was outlawed. Black workers had finally entered the mills as regular employees.

After 1919 in Gary two organizations, in particular, intervened to build black pride and organization: the NAACP and the UNIA, United Negro Improvement Association, headed by Marcus Garvey. Almost every black steelworker who rose to leadership in the early United Steelworkers’ Union passed through the UNIA. There they learned Black Pride. When the Steelworker Organizing Committee (SWOC) came to town in the 1930s, Black workers signed up in big numbers. Every local union built in the Region had a black vice-president.

One of the most important lessons black workers learned in the Great Steel Strike of 1919 was best expressed by Curtis Strong decades later: “You have to coalesce with whites, “ he maintained, “but if you don’t organize yourselves first, you will always be on the bottom!”

Ruth Needleman, Professor Emerita, IU, Author, Black Freedom Fighters in Steel

Spread the word