Since 1851, many remarkable black men and women did not receive obituaries in The New York Times. This month, with Overlooked, we’re adding their stories to our archives.

When Homer Plessy boarded the East Louisiana Railway’s No. 8 train in New Orleans on June 7, 1892, he knew his journey to Covington, La., would be brief.

He also knew it could have historic implications.

Plessy was a racially mixed shoemaker who had agreed to take part in an act of civil disobedience orchestrated by a New Orleans civil rights organization.

On that hot, sticky afternoon he walked into the Press Street Depot, purchased a first-class ticket and took a seat in the whites-only car.

The civil rights group had chosen Plessy because he could pass for a white man. It was asserted later in a legal brief that he was seven-eighths white. But a conductor, who was also part of the scheme, stopped him and asked if he was “colored.” Plessy responded that he was.

“Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” the conductor ordered.

Plessy refused.

Before he knew it a private detective, with the help of several passengers, had dragged him off the train, put him in handcuffs and charged him with violating the 1890 Louisiana Separate Car Act, one of many new segregationist laws that were cropping up throughout the post-Reconstruction South.

For much of Plessy’s young life, New Orleans, with its large population of former slaves and so-called “free people of color,” had enjoyed at least a semblance of societal integration and equality. Black residents could attend the same schools as whites, marry anybody they chose and sit in any streetcar.

French-speaking, mixed-race Creoles — a significant percentage of the city’s population — had acquired education, achieved wealth and found a sense of freedom since before the Civil War. But as the century drew to a close, white supremacy movements gained traction and pushed hard to quash any notion that people of color might ever attain equal status in white America.

The Separate Car Act spurred vigorous resistance in New Orleans. Plessy, himself an activist, volunteered to be a test case for the local civil rights group, Comite’ des Citoyens (Citizens Committee), which hoped eventually to put Plessy’s case before the United States Supreme Court. The group posted his bail after his arrest.

When his case was heard in criminal court four months later, Judge John Howard Ferguson chose not to hold a trial and instead, he upheld the constitutionality of the Louisiana Separate Car Act, which enabled Plessy’s legal team to appeal the decision and keep Plessy out of jail.

Plessy’s lawyer, Albion Tourgée, then appealed the ruling before the Louisiana Supreme Court, arguing that the Separate Car Act violated the 14th Amendment, which, ratified in 1868, guaranteed equal protection under the law. But the higher court upheld Judge Ferguson’s decision.

It would be four years until the Supreme Court heard Plessy v. Ferguson.

In his argument before the Court, Tourgée asserted that the doctrine of “separate but equal” was a sham. “Its only effect is to perpetuate the stigma of color — to make the curse immortal, incurable, inevitable,” he argued.

His words fell on mostly deaf ears. On May 18, 1896, the justices, eight white men of privilege, ruled against Plessy, 7-1.

The sole dissent was by Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Kentucky native and Civil War veteran, who famously declared, “Our Constitution is color blind.”

The ruling came to be regarded as one of the most ignominious in the Supreme Court’s history. It would define the Jim Crow era, in which people of color were summarily segregated from not only trains but also schools, theaters, public buildings, lodgings, lunch counters and much else over the next 58 years, until the Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education, unanimously dismissed the “separate but equal” doctrine in ruling in 1954 that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

By then Plessy had long been dead.

Plessy’s train-car protest presaged Rosa Park’s refusal to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., in 1955, but where she became revered in civil rights lore, he all but vanished into obscurity, his name synonymous with an odious Supreme Court ruling.

“This case is infamous for several reasons,” Laurence Tribe, a constitutional law professor at Harvard Law School, said in a telephone interview. “First, separate is almost never really equal. Second, separate is symbolically and psychologically unequal when it is recognized to have the social meaning that whites are too good to mix with blacks, or that one race is essentially superior to the other.”

He added: “The ruling suggested that if people of color feel inferior as a result of these laws, it is their own fault. It is essentially part of blaming the victim and pretending that the feeling of subjugation and subordination is simply a problem in the mind of the person on the receiving end.”

Steve Luxenberg wrote in his 2019 book, “Separate,” that Plessy v. Ferguson’s “baneful effects lasted longer than any other civil rights decision in American history.”

“It gave legal cover to an increasingly pernicious series of discriminatory laws in the first half of the 20th century,” he wrote.

After the Supreme Court decision, the Citizens Committee in New Orleans issued a final statement on the case, saying, “In defending the cause of liberty, we met with defeat but not with ignominy.”

Homère Patris Plessy (later changed to Homer Adolph Plessy) was born in New Orleans on March 17, 1863, soon after Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. His parents, Joseph Adolphe Plessy, a carpenter, and Rose Debergue Plessy, were Creole.

Homer’s paternal grandfather, Germain Plessy, was a white Frenchman born in Bordeaux. He had emigrated to Haiti and then fled to New Orleans along with thousands of other expatriates during a slave rebellion in the 1790s. In New Orleans, he married Catherine Mathieu, a free woman of color, with whom he had eight children, including Homer’s father.

Homer’s father died when he was 6, and his mother married Victor M. Dupart, a shoemaker and political activist whose wife had died, leaving him with six children. Dupart was active in the social, political and masonic organizations that were part of the fabric of New Orleans society.

In the 2003 book “We as Freemen,” Keith Weldon Medley wrote that the extended Dupart family had influenced his joining such organizations as the Unification Movement, an early civil rights group.

Like his stepfather, Plessy became a shoemaker. In 1887 he became vice president of the Justice, Protective, Educational and Social Club, a group dedicated to reforming public education in New Orleans. In 1888 he married Louise Bordenave, and the couple moved to the Faubourg Tremé neighborhood, just north of the French Quarter. The Tremé, which is known as the birthplace of New Orleans jazz, was a center of “diversity, culture, politics and music” filled with free people of color who had migrated from Haiti and Cuba, Medley wrote.

He added: “Homer Plessy spent the first half of his life exercising the newfound rights that were denied his parents. He would spend the 1890s trying to keep those rights.”

After the Supreme Court decision, Plessy returned to district criminal court, where he was found guilty, paid his $25 fine, and lived a quiet life. He and his wife had no children.

With the industrial age wiping out much of the handmade shoemaking industry, he abandoned the trade and worked as a laborer, warehouseman and clerk. He later worked for the black-owned People’s Life Insurance Company as a collector. Plessy died on March 1, 1925, and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery in New Orleans. He was 61.

At a book signing in 2004, Medley introduced Keith M. Plessy, a distant relative of Homer Plessy, to Phoebe Ferguson, a documentary filmmaker and the great-great granddaughter of Judge Ferguson.

Phoebe Ferguson began to apologize for her ancestor’s decision and for the segregation it triggered. “I stopped her,” Keith Plessy said in a phone interview. “I told her, ‘It’s no longer Plessy versus Ferguson; it’s now Plessy and Ferguson. And we became great friends.”

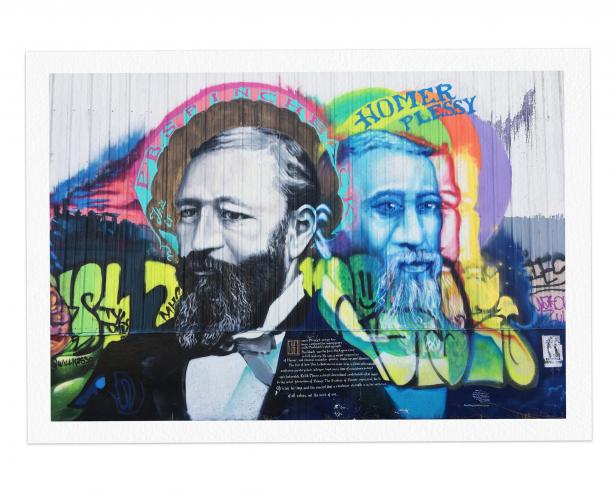

In 2009, Plessy joined forces with Ferguson to found The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation to preserve Homer Plessy’s legacy and influence how it is taught. The organization petitioned New Orleans to hold an annual Homer Plessy Day on June 7 and to rename a stretch of Press Street as Homer Plessy Way. A plaque explaining his act of civil disobedience now stands on the spot where he was arrested.

Correction: Feb. 1, 2020

An earlier version of this obituary misstated how Judge John Howard Ferguson handled Plessy's case in criminal court. He chose not to hold a trial. He did not find Plessy guilty.

Spread the word