We are at an inflection point in the 400-year history of U.S. racism and the fight to end it. The uprising that has followed the police murder of George Floyd has changed the political equation, shifting public opinion and galvanizing a new cohort of racial justice fights determined to make a big dent in anti-Blackness and all institutional manifestations of white supremacy.

Exactly how much change can be achieved in the next stage of struggle is yet to be determined. Translating an uprising into concrete victories is never easy or automatic. But there is much to learn from previous experience. This is not the first time that an uprising against anti-Black racism has opened the door to significant change.

For example, there’s the little known rebellion of Black Air Force personnel at Travis Air Force Base in California at a time when the U.S. still had more than 150,000 troops deployed in Vietnam. This May 1971 uprising convinced the top Pentagon brass and the Washington political establishment that they had to change the nature and culture of all branches of the military.

FLASHPOINT OF BLACK MILITARY RESISTANCE

In 1971 the Vietnam War seemed endless, but the tide had turned: finally there was overwhelming public sentiment against the war. And resistance within the military itself, with protests, refusals to obey orders and even mutinies extending from state-side bases to the frontlines in Vietnam. Dissent by soldiers, airmen, sailors and marines often saw Black troops in the lead.

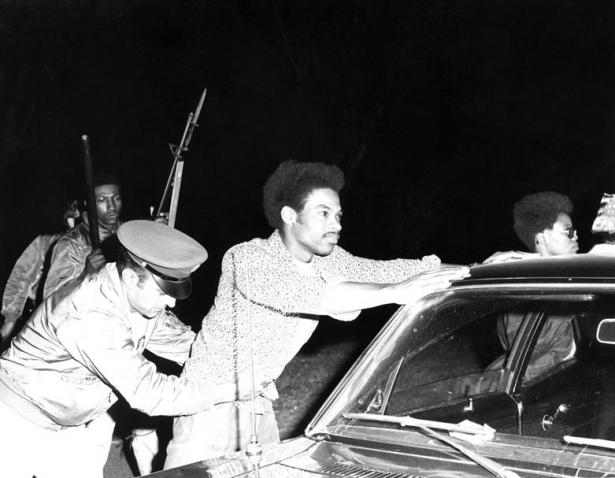

A pivot point in this resistance was the four-day uprising by Black air force personnel at Travis AFB that May. Accounts vary about how many airmen and women members of the WAF (Women in the Air Force) program took part. The Sacramento Bee (29 June 1971) stated that 500 Airmen and WAF were involved, 24 were injured and 35 were detained, with most released as of that date. Estimates of the damage also varied. One source claimed an officer’s club was burned to the ground. In fact, the fire was limited to the charring of two rooms of a transient barracks in the bachelor officers’ quarters. One person, Fireman James T. Morsberger (age 47), suffered a heart attack and died while fighting the fire, which the Sacramento Bee speculated was caused by five teenagers.

The resistance was so threatening that military personnel from other bases and the Fairfield City police had to be brought in to restore order.

Less than a month later, the breakdown of discipline throughout the military was acknowledged in the Armed Forces Journal. In an article titled “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,” Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr. wrote:

“The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States…By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous.”

BACKGROUND TO THE TRAVIS UPRISING

The conditions which had led to the rebellion at Travis AFB were detailed by the local anti-war newspaper Travisty:

“The intensity and duration of the disturbances were attributable to the long history of racism in this country, abetted by what life is like in the Air Force, and conditions on Travis. There was the stress of deployment to Nam, poor housing, petty harassment, and racist discrimination against Black airmen. When it finally boiled over, shooting occurred, a colonel’s car was overturned, and small groups went around beating up random individuals. The abysmal morale and breakdown in discipline that was rampant in Vietnam was reproduced here at Travis. During the riots, there was arbitrary detainment and arrest, with immediate shipping out of some airmen. Charges were brought – almost solely against Black airmen…The rioting started because of an incident involving Black and white airmen. White airmen repeatedly interrupted Black airmen from Nam who were giving the dap (greeting)…Two black airmen, Brother Byes and Brother Kays, were taken into custody, but no whites were. (Mays was arrested Sunday, with no reason given, as he got out of a car in the 1300 area.)”

As Airman Gregory Price put it:

“The problem was we wanted Airman Mays and Airman Byes released because they were arrested, as far as we know, for their political beliefs. Nobody would tell us anything about what was happening to them. Black officers came in and told us that they were shipping the brothers away. At this time let me tell you we were non-violent. We didn’t hurt nobody, we didn’t touch nobody. When we came out onto the streets there were SP (Security Police) trucks who were taking pictures of every Black person that walked out of the Snake Pit (snack bar).

“At that time there were a group of white airmen standing on the bannisters in the 1300 area calling us n—-s, ‘Go back to Africa,’ stuff like this. I said, Be cool, because they’re wrong and we’re right, because we weren’t causing any trouble…We could have caused damage right there when they called us names. We said we’re going over to the slam (jail) and see if Brother Mays and Brother Byes are still there.

“When we left the Snake Pit we decided to walk across the baseball diamond. Around 150-200 people. We were strong, because it was something that concerned every Black on this base. As we were walking across we came up the hill to the hospital. All the augmentees [service members on temporary duty assignments] were out there. They were strong with bayonets, night-sticks, dogs, and everything else. The confrontation started…There was a sister that was conversing with a pig; he struck her and she went down. Brothers went to her aid, they were attacked too. Everybody saw what was coming down, like they were really hitting us with sticks, you know, this was for real. They had bayonets and they had guns. The brother went to her aid and he tried to pick her up and take her to safety and he was beaten by sticks. So the Blacks fell back from a confrontation with the man at this time, and as we were falling back we picked up rocks and started throwing them. We were mad, because we weren’t causing any trouble but they came on with violence first.”

AFTERMATH – THE DELLUMS HEARINGS

In November 1971, after a summer in which the brass tried to implement reforms, freshman Congressman Ron Dellums held hearings at Travis on racism in the military. Over 200 GI’s attended the day-long hearings at the Crosswinds Community Center on base. Testimony by airmen offered a bleak picture of the reforms that had been promised:

Ron Dellums: This was an incident on Travis Air Force Base back in May. This is now November. Can you tell me whether the conditions that gave rise to this situation have been corrected, whether the programs that have been instituted over the past few months have been operable or realistic?

Airman Price: Today you could look at it and actually say nothing has come of it. Because to this very day the young Black airman has no way of voicing his opinion that he’s being crucified for his beliefs… The Equal Opportunity Council has been a white program, can I say, ‘cause those who are at the EOC are not my brothers. Two stripers, you know, they’re not represented.

Dellums: To your knowledge, is the EOC on this base dealing with the issue of job assignments in relationship to minorities?

Airman Jeff Renfro: Not from what I see happening at my place of employment, no.

Levi Bolton (civilian worker): The point is that this base, this area is a racist area. Let’s just face it. In 1940 through 1944 they brought up to this area (on barges) condemned housing to house Black and poor people. These were rat-infested. You want to know how I know they was rat-infested? I lived in them. I have skinned rats that I can show you that was in my back yard. This is the problem, housing for these young men. Not some of the places, but all of them discriminate, one way or another.

FORCING A CHANGE

The significance of the uprising did not lie in the magnitude of the physical injuries sustained or property damage, but in the determination displayed by the demonstrators. The fact that a rebellion like this took place at a state-side base alarmed the military brass. It was unthinkable that GIs would “bring the war home.”

The connection between the violence at Travis and the change in military policy is clear from a very pro-military piece, “From Travis to Today: An Analysis of Racial Progress in The US Air Force Officer Corps Since 1971,” by AaBram G. Marsh, Major USAF, published in 2009:

“This paper begins in 1971 because it was after racial violence rocked various Air Force installations, most notably the four-day riot at Travis AFB that same year, that its leaders took an active and progressive role in improving the conditions under which Blacks served, as well as the retention and development of its personnel…The service’s race riots of the early-1970s revealed that commanders and officers (who were almost exclusively white males), possessed limited sensitivity to and understanding of the plight of the increasing population of Black enlisted airmen.”

The military brass feared that what happened at Travis would spread to other bases on US soil. The uprising became a tipping point that led to better treatment of African Americans within one of the most powerful institutions in the country. Beyond that, it was part and parcel of a general rebellion throughout the military that played a key role in ending U.S. aggression in Vietnam.

Today’s uprising has more ambitious goals: completely dismantling institutions like the police (and for many, the U.S. military) whose very purpose is racist and imperial repression. The lesson from the rebellion at Travis and the entire U.S. military in 1971 does not lie in the specific demands of that rebellion. It is that uprisings led by African Americans in any institution, or in society as a whole, scare the hell out of the powers-that-be and have the capacity to gain widespread support and force social change. If all sectors of today’s progressive movement take this to heart, we will be better equipped to both Defend Black Lives and advance the struggle for justice and peace across the board.

An Appendix containing extensive testimony from the Air Force investigation may be found at https://medium.com/@jonknowles8_98385/appendix-to-uprising-by-black-airmen-at-travis-afb-in-may-1971-380bc7b07315?sk=4c4826a14baec931753be988770d1851

Jon Knowles was in the U.S. Army from 1961 to 1963 and was active in the antiwar movement from 1965 to 1974. In 1971 he co-founded the Travis GI Support project, which published the antiwar newspaper "Travisty" and opened "Liberation Hanger," a coffee house and counseling center just outside Travis Air Force Base.

Spread the word