Karl Marx contended that international trade could expand, especially if countries allowed for an increase in production at a lower cost, as David Ricardo had said. However, Marx also added that, despite this immediate gain, exchange operates at the expense of less industrialized economies and actually turns out to be unequal, that is, it is a form of expropriation, as soon as we take into account the quantities of labor and productive efforts that go into the exchanged goods.1 This can be seen if a “less developed” country presents a lower labor productivity than that of its foreign trade “partners,” with fewer hours of work incorporated into the merchandise it imports compared to the hours included in its own exports. The ratios of labor quantities demanded by exports and imports (what will later be called “factorial terms of trade”) are in this case unfavorable to the least “advanced” country, which is exploited with regard to the respective labor contributions. Marxists after Marx, starting with theoreticians of the capitalist world system, would show that the extent of the inequalities between exchange countries can be found to depend on the differential in labor remuneration, lower at the periphery than at the center, with equal productivity.2

By revealing the unequal or expropriative nature of imperial exchange, Marx thus refuted the vision of international trade in which competition leads to equalizing or correcting inequalities, and rather underlined the mechanisms of domination and exploitation affecting less industrialized economies, leading to their submission to the rich capitalist countries.3 If Marx thought that “commercial freedom hastens the social revolution” and chose to “vote in favor of free trade,” he did not fail to insist that the latter aggravates inequalities between countries, shaping an international division that works in accordance with the interests of the most powerful capitalists. Without adhering to protectionism, Marx radically rejected the normative conclusions of mainstream economists and supporters of free trade.4

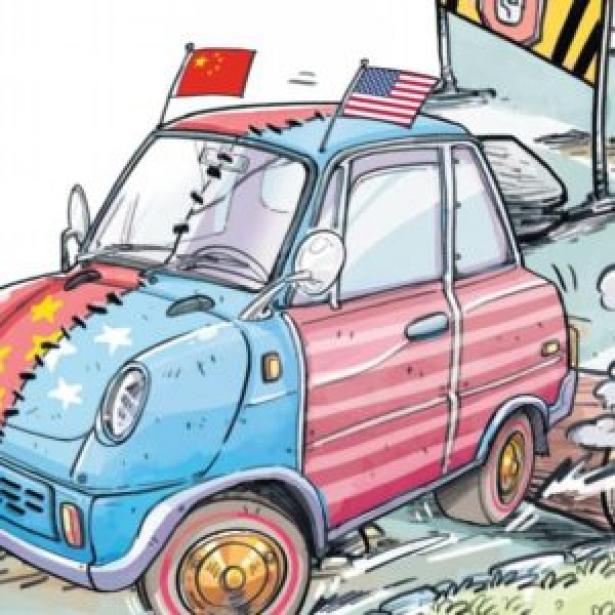

Could Marx then help us understand certain aspects of current U.S.-China relations? The very large U.S. trade deficit vis-à-vis China was the main pretext for Washington to trigger, starting in the first half of 2018, what is customarily called a “trade war” against Beijing. Beyond accusations of intellectual property “theft” and other courtesies, the reasons invoked by the U.S. administration relate to supposedly “unfair” competition from China. In this framework, China purportedly accumulates the advantages of, on the one hand, increased exports through low wages and an undervalued national currency, and, on the other hand, imports hindered by subsidies to domestic firms and heavy regulatory constraints impeding access to its domestic market.5 Does the U.S. bilateral deficit not provide irrefutable proof that Donald Trump is right in saying that “the Chinese are extirpating hundreds of billions of dollars [from the United States] every year and injecting them into China” (while claiming, too, that President Xi Jinping is “one of very, very good friends”)?6 The recent changes in the configuration of value chains that have seen China gradually occupy a strategic place in globalized supply networks certainly tend to complicate the analysis. But how can anyone deny the evidence that all these dollars are indeed transferred from the deficit country to the surplus country?

As we know, since the 1980s (and even ’70s), increasingly deep bilateral trade deficits have been observed to the detriment of the United States and to the benefit of China. Differences exist in the exact calculated deficit amounts between U.S. data (U.S. Department of Commerce) and Chinese data (China Customs Administration)—these valuation differences being due to, inter alia, how reexports from Hong Kong, transportation costs, and travel expenses of nationals of the two countries are taken into account.

This deterioration only slowed down (temporarily, before accelerating again) as a result of the impact of the crises that shook the U.S. economy in 2001 (the bursting of the “new economy” bubble) and 2008 (the so-called “subprime” crisis, which reverberated in China starting in 2009, but especially from 2012 on); the appreciation of the yuan (in 2005 and in 2011); and the financial crisis of summer 2015 on the Chinese stock markets. Slowly degraded in the 1990s at first, then sharply in the 2000s and 2010s, this bilateral balance crossed the $100 billion mark in 2002, $200 billion in 2005, then $300 billion in 2011, before reaching, for goods alone (excluding services), the record deficit of $419.5 billion in 2018. China had by this date officially become the very first trading partner of the United States for the trade of goods, for a total of $659.8 billion: $120 billion in U.S. exports and $539.5 in imports. Meanwhile, trade in services had a surplus of $40.5 billion in favor of the United States in 2018.

It was precisely in 2018 that Washington launched the trade war against China. The initial measures were taken in January, consisting in sharply increasing the customs tariffs borne by certain products imported from China (such as household equipment and photovoltaic solar panels). In March, further barriers to imports from China (metallurgy, automobile, aeronautics, robotics, information and communication technologies, medical equipment, and more) followed. In April came the sanctions against Chinese companies targeted by bans on the use of U.S.-made inputs.

By June 2019, as tariff increases hit new sectors, China was no longer the United States’s largest trading partner, with the latter’s partners in the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico and Canada, overtaking China. At the end of 2019, the U.S. trade deficit with China was significantly reduced and amounted to $-345.6 billion, below that of the end of Barack Obama’s second term—a shift that was visible from the first months of 2019.

Could it be then that Trump is right and on the way to winning his trade fight? Mainstream economists claim that the trade between the United States and China is unfair, but is this really the case?

The Measure of Unequal Trade

At the cost of certain technical conditions and assumptions, the respective values in labor contained in the goods and services exchanged by the United States and China in their bilateral trade can be calculated.7 This is what we did, using two separate methods.8 The first method consists in directly estimating the unequal exchange as the ratio between the contents, measured in labor integrated into U.S.-China exchanges: China exports a quantity of hours of work performed by Chinese workers and, in return, imports another quantity of hours by U.S. workers to which the surplus of the trade balance is added—that is, additional hours by these same U.S. workers corresponding to this bilateral balance. We also need to assess how many hours of work are equivalent to a U.S. dollar, both in the United States and China. Our calculations, performed at current prices, must convert currencies using the official exchange rate.

The results we obtained for the last four decades (from 1978 to 2018) highlight the existence of an unequal exchange between the United States and China, at the expense of the latter and in favor of the former. The respective changes in labor contents integrated in the traded goods were very different in the two countries. For China, we see a strong rise until the middle of the 2000s, then an abrupt fall, and finally a stabilization in the early 2010s, but, for the United States, we see a much more moderate evolution of steady increases. We then find that between 1978 and 2018, on average, one hour of work in the United States was exchanged for almost forty hours of Chinese work. However, from the middle of the 1990s—a period of deep reforms in China, especially in fiscal and budgetary matters—we observed a very marked decrease in unequal exchange, without it completely disappearing. In 2018, 6.4 hours of Chinese labor were still exchanged for 1 hour of U.S. labor. Could the erosion of this U.S. trade advantage then explain the outbreak of its trade war against China?

We also adopted a second method to check these results. In our first method, we compared the average necessary labor times required to manufacture the traded goods, allowing us to directly assess the unequal trade. However, the appropriation of produced wealth between countries can in fact be rigorously measured only through the bilateral transfer of “necessary social work time”—that is, “international values.” The latter can be estimated empirically, although the calculations are not easy. In addition, using the previous method, it was only possible to calculate living labor directly incorporated into exports, while the gross product also includes labor materialized in the various means of production mobilized. Our second method is based on the new interpretation of the labor theory of value, in order to overcome the mentioned limitations of the first method and examine more precisely the extent of unequal exchange. While our first method measures labor content directly incorporated into the exchange, our second method focuses on the international values, using input-output tables.9

The calculation of unequal exchange is closely related to the application of input-output methods because it implies the measurement of the flows of goods traded and the values underlying the division of labor between the two countries. The value that can be measured is actually the amount of total labor input contained in merchandise, which includes the amount of direct labor and that of “materialized” labor—the latter resulting from labor contained in intermediate goods (or intermediate production processes) within overall commodity production. The idea for measuring this value is thus to use an input-output matrix to obtain labor inputs. However, while unequal exchange involves comparisons of prices, the unit of labor input is time. Thus, the time unit of value needs to be converted into a monetary unit, for which the value measurement scheme based on the new interpretation of labor value theory is a possible solution. A global value chain is a form of an integrated division of labor, implying a dual dimension (countries × industries). To represent it, the most suitable tools are the multiregional input-output tables. Here, we use such detailed tables of commodity flows with measurements of values contained in the merchandise in order to estimate international value flows and, finally, by comparing the latter with currency flows, the amounts of unequal exchange.

In this alternative framework, we thus assess the quantities of newly created international values in the different sectors of each country, using the expression of the exchange rate in purchasing power parity to reflect the share of a country’s product in world production and to reduce the impact of real exchange rate fluctuations. We then calculate the difference between the international values newly created by each economic sector of each country and the prices on the world market. In total, thanks to a world trade matrix constructed from international input-output tables, for each sector in the two countries, we obtain the values of transfers from or to other recorded economic activities, therefore actually transferring the net values, that is, the extent of unequal exchange. Given the available data, our calculations could only be for the years between 1995 and 2014, for fifty-five sectors, and forty-three countries, including the United States and China. If we focus on these last two countries, the results we obtain with this second method confirm those previously collected with the first one: inequality operated in U.S.-China trade over the period between 1995 and 2014. In total, transfers of international values largely took place for the benefit of the United States. Expressed in current dollars, at the end of the period, this “redistribution” approached $100 billion, or nearly 0.5 percent of U.S. value added.

The Erosion of the U.S. Advantage

What our results show is that the United States, as a world hegemonic power, is finding it increasingly difficult to maintain its advantage and come out on top of this competition, and therefore to bear all the implications of free trade, for which it once defined the rules to its advantage. China has indeed succeeded in significantly reducing the importance of this unequal exchange, with its disadvantage in the transfer of wealth gradually diminishing: the proportion of this unfavorable transfer in the Chinese added value fell from -3.7 percent to -0.9 percent between 1995 and 2014. As a matter of fact, China had to trade fifty hours of Chinese labor for one hour of U.S. labor in 1995, but only seven in 2014.

On top of this, the sectoral analyses that can be drawn from the application of our second method of calculating unequal exchange are very enlightening. Although forty-three out of the fifty-five sectors of activity (78 percent of them) considered by our study between 1995 and 2014 highlight transfers of value directed from China to the United States (the most significant being textile, clothing, and leather-goods manufacturing, as well as the manufacturing of furniture and other supplies), twelve other sectors are at the origin of transfers of values going in the opposite direction—that is, operating to the detriment of the United States. These latter activities include: the manufacturing of computer, electronic, and optical products (with $6.9 billion transferred from the United States to China in 2014); agriculture and farming; hunting and hunting-related activities ($3.1 billion); the manufacturing of motor vehicles and trailer and semi-trailer services ($1.1 billion); and the manufacturing of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations ($422 million, still calculated for 2014).

The first of these sectors encompasses one of the main axes of the offensive launched by the Trump administration—as much against China as against the giant U.S. multinational firms of “globalism,” especially those operating in new information technologies and communications, which he criticizes for having relocated to China and claims he will bring back to the United States. Trump is often dismissed as being a “madman,” but he is in fact the product and eminent representative of one of the factions of high finance that currently dominate the U.S. economy—the “continentalist” faction, opposed to the “globalist” faction.10 The second sector, that of the automobile industry, is one of the pillars of the U.S. economy, but was badly shaken (and abundantly rescued) after the crisis of 2007–09. The third sector, agriculture and livestock, is one that has suffered some of the harshest Chinese retaliation in the form of custom taxes imposed on agricultural goods imported from the United States (especially from states that are big producers of agricultural goods as well as big proponents of Trump in the presidential election, such as Kansas, for example)—Chinese restrictions that have compounded the U.S. disadvantage. The fourth economic sector mentioned among the United States’s weakest is the manufacturing of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations. The vital strategic importance of this sector has recently, and painfully, been revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Under these conditions, can we not wonder if launching a trade war would not also constitute an attempt on the part of the United States to limit the transfers of values drawn from these fundamental sectors by China?

Challenging Global Hegemony

Beyond the tirades of political forums and ornamentations of diplomatic negotiations, the economic questions that concern us here are complex. A plurality of overlapping factors help explain the observed downward trend in the ratio of labor exchanges included in bilateral trade. Some of the most influential, among others, are undoubtedly the fluctuations of exchange rates and the respective productivity dynamics, which in particular reflect changes in production and the technological gaps between the two countries.

The exponential increase in Chinese exports over the last thirty years has been carried out on the basis of successful—but long and difficult—industrialization and rigorous control over the country’s openness to the world system, integrated within the framework of a thoroughly controlled “development strategy.”11 This is why the content of exports has been able to be gradually modified so as to concern increasingly elaborate production processes, to the point that, today, high-tech goods and services represent more than half of the total value of the merchandise exported by China. Thanks to technological innovations in all areas (including robotics, nuclear power, space), dominated nationally more and more, the country’s productive structures have been able to evolve from made in China to made by China. Over several decades, the growth rate of labor productivity gains has accelerated, on average, from 4.31 percent in the 1980s to 7.28 percent in the 1990s, 11.72 percent in the 2000s, and even 14.12 percent for 2010. This acceleration has thus made it possible to support the very sustained increase in industrial wages (in real terms), but the slight increase in the Chinese “labor cost” relative to competitors from the South (South Korea, Mexico, Turkey, and so on) does not diminish the competitiveness of national companies, or even their margins. At present, exports—and foreign direct investment, since more than half of exports are made by foreign transnationals established in China—instead play a supporting role in the country’s development.

Currency and trade wars invariably go together. The trade war against China was launched by the U.S. administration in a preexisting context, where, for decades, the United States exerted extreme pressure through its national currency—which is also the international reserve currency—on all other world economies. Aimed at trying to improve the price competitiveness of exports from one or the other of the two countries, the downward competition over a weak dollar or a weak yuan recently gained speed when the monetary authorities in China reacted to the U.S. sanctions by letting their national currency depreciate. The yuan was therefore “devalued” in August 2019. But was it really undervalued before then?

The boom in exports, on which the Chinese growth “model” relied in part—but only in part—has crystallized a major point of tension in international economic relations. Indeed, the renminbi, whose currency unit is the yuan, has long been said to be markedly undervalued, according to the media in the United States and elsewhere. This supposed undervaluation, it is claimed, was at the origin of the worsening of the U.S. trade deficits, because exported Chinese goods, already very cheap, were made even more competitive in world markets by a yuan that was kept artificially depreciated. Hence the redoubled pressure from Washington for the appreciation of the Chinese currency against the dollar, which led, despite Beijing’s reluctance and resistance, to the revaluations of 2005 and 2012. In between these two years—that is, between the Chinese monetary authorities deciding to no longer link variations in their currency to the dollar (July 2005) and the last revaluation carried out (April 2012)—the real value of the yuan appreciated by 32 percent against the dollar.

The debates between economists on the “fair value” of currencies are controversial. However, among the criteria discussed, it is above all the ratio between the current account balance and the gross domestic product that is used by the various expert advisors to U.S. governments (under presidents Obama and Trump). The benchmark thus used to define the so-called “equilibrium exchange rate” would be a ratio of surplus or deficit of the balance of current payments to gross domestic product of between +/- 3 or 4 percent. But if we apply this criterion to China, marked by the importance of bilateral relations with the United States, we see that the Chinese ratio has fallen from over 10.6 percent in 2007 to less than 2.8 percent in 2011, and only 1.4 percent in 2012. And this criterion continued to be met thereafter, settling just above 3.5 percent, thus within the U.S. “shooting window.” In the early 2010s, China therefore managed to bring its balance of current payments to gross domestic product ratio down to a level deemed “reasonable,” meaning compatible with the exchange rate of the yuan against the dollar. The proportion of exports in gross domestic product has been brought under control: after having soared to more than 35 percent in the mid–2000s, it has fallen below the 20 percent mark—that is, ten points of gross domestic product below the world average (30 percent in the last ten years). In China, this ratio of exports to gross domestic product, which is of less than 20 percent, is now lower than that of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (28 percent) and, even more markedly, of the euro area (45 percent). It is also this openness control that has guaranteed China relatively more stable conditions in terms of exchange rates (and inflation rates) than other countries.

Consequently, the “undervaluation” of the yuan is not as obvious as often claimed (unlike the deterioration in China’s terms of trade, which is very real but generally ignored), as soon as we refer to the benchmark most used by the U.S. administration itself. This has not, however, prevented the United States, despite the gigantic twin imbalances that characterize its economy (fiscal deficit and trade deficit), from pursuing what many observers have called a “currency war” through the depreciation of the U.S. dollar on the foreign exchange markets, and attempting to impose on Beijing the terms of what looks like a “surrender,” one of the implications of which is the devaluation of the dollar reserves held by the Chinese monetary authorities.12 Nevertheless, it is China that is often accused of hardening this turn from commercial war to monetary war.

Could this be because China has succeeded in deploying a nonfinancial and nonwarlike development project that autonomously and effectively contests the power bloc of U.S. high finance, which feeds on fictitious capital and imposes its crises and wars on the world?

The hypothesis that we will therefore formulate is that, added to a currency war that preexisted it, the trade war launched by Washington against Beijing, within the context of the “New Cold War,” could be interpreted as an attempt by the Trump administration to curb the slow, continuing deterioration of the advantage that the United States has managed to extract from its trade with China for at least four decades, and thus also to maintain its crumbling world hegemony. China has certainly accumulated revenues from its bilateral trade surpluses, but the corresponding gains have been offset by the fact—highlighted by our calculations measuring the bilateral unequal trade—that it is mainly the United States that has profited from this trade in terms of the labor time embodied in the merchandise traded.

While it is far from certain that Trump’s trade war will succeed in bending China like Ronald Reagan did to Japan in the 1980s, the very close trade and monetary interweaving of the first two economies of the world—one superpower in decline, the other on the rise—poses extremely worrying risks for the two countries, as well as the world economy. It is clear that a significant amount of the dollars collected by China from its trade surpluses return to the United States in the form of massive purchases by the Chinese monetary authorities of treasury bills issued by the United States for the very purpose of financing their own trade deficits.

Let us then turn to Trump, to ask him simply: “If we were to take off the masks for a moment, who would be the real ‘thief’ in this whole thing?”

Notes

- ↩ Marx’s analysis is infinitely more complex than the brief presentation we lay out here, constrained as we are by space. For a more complete account of his thinking on the question at hand, we invite the reader to refer, among others, to: Rémy Herrera, “La Colonisation vue par Marx et Engels: évolutions (et limites) d’une réflexion commune,” in Le Colonialisme, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (Paris: Éditions Critiques, 2018), 7–73. Let us only point out that some of the most important (and difficult) passages of Marx’s interpretation of the effects of international trade can be found in: Karl Marx, Le Capital, vol. 1, section 8, chap. 31 (Paris: Éditions sociales, 1974), 195–201; Karl Marx, Le Capital, vol. 3, section 4, chap. 20 (Paris: Éditions sociales, 1974), 341–42; Karl Marx, Fondements de la critique de l’économie politique and Matériaux pour l’“économie,” in Œuvres – Économie II (Paris: Gallimard, 1968), 251, 489–97; and Karl Marx, Théories sur la plus-value (Paris: Éditions sociales, 1975), 636.

- ↩ See Samir Amin, Accumulation on a World Scale (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974) and many others, after Arghiri Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972).

- ↩ Among others, see the articles that Marx devoted to the colonization of India, such as in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, On Colonialism (Moscow: Foreign Languages, 1968).

- ↩ Karl Marx, “On the Question of Free Trade” (speech, Democratic Association of Brussels, January 9, 1848).

- ↩ Compare this to Donald Trump’s tweets or the declarations by Mike Pence or Peter Navarro, for example.

- ↩ “Remarks by President Trump at Signing of the U.S.-China Phase One Trade Agreement,” White House, January 15, 2020, available at whitehouse.gov.

- ↩ On this subject, see Bill Gibson, “Unequal Exchange: Theoretical Issues and Empirical Findings,” Review of Radical Political Economics 12, no. 3 (1980): 15–35; Akiko Nakajima and Hirochi Izumi, “Economic Development and Unequal Exchange among Nations: Analysis of the U.S., Japan, and South Korea,” Review of Radical Political Economics 27, no. 3 (1995), 86–94; and Zhixuan Feng, “International Value, International Production Price and Unequal Exchange,” in Economic Growth and Transition of Industrial Structure in East Asia, ed. Zhixuan Feng et al. (Singapore: Springer, 2018).

- ↩ Zhiming Long, Rémy Herrera, and Zhixuan Feng, “Turning One’s Loss into a Win? The U.S. Trade War Against China in Perspective” (mimeograph, CNRS—UMR8174, Centre d’Économie de la Sorbonne, Paris; University of Tsinghua, Beijing; University of Nankai, Tianjin, 2020), 17.

- ↩ See, in particular, Duncan Foley, “Recent Developments in the Labor Theory of Value,” Review of Radical Political Economics 32, no. 1 (2000), 1–39; Jie Meng, “Two Kinds of MELT and Their Determinations: Critical Notes on Moseley and the New Interpretation,” Review of Radical Political Economics 47, no. 2 (2015), 309–16. This second method, as an alternative to the first one, is inspired by the model proposed by Andrea Ricci in “Unequal Exchange in the Age of Globalization,” Review of Radical Political Economics 51, no. 2 (2019), 225–45.

- ↩ Wim Dierckxsens and Andrés Piqueras, 200 Years of Marx: Capitalism in Decline (Hong Kong: International Crisis Observatory, Our Global U, 2019).

- ↩ Rémy Herrera and Zhiming Long, “The Enigma of China’s Growth,” Monthly Review 70, no. 7 (December 2018): 52–62; Rémy Herrera, Zhiming Long, and Tony Andréani, “On the Nature of the Chinese Economic System,” Monthly Review 70, no. 5 (October 2018): 32–43.

- ↩ See Martin Wolf, “Why America Is Going to Win the Global Currency Battle,” Financial Times, October 12, 2010.

Zhiming Long is an associate professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Zhixuan Feng is an assistant professor at Nankai University in Tianjin. Bangxi Li is an associate professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Rémy Herrera is a researcher at the National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris.

Monthly Review survives in large part through the support of our Associates, who have been the bedrock of the magazine since its earliest years. Basic magazine subscriptions cover little more than the costs of printing and mailing, and electronic subscriptions, while growing, make only a modest impact on our bottom line. We have no foundation support, no endowment, no deep pockets. Please become an Associate or, if you have joined already, consider renewing at the same or a higher level.

Spread the word