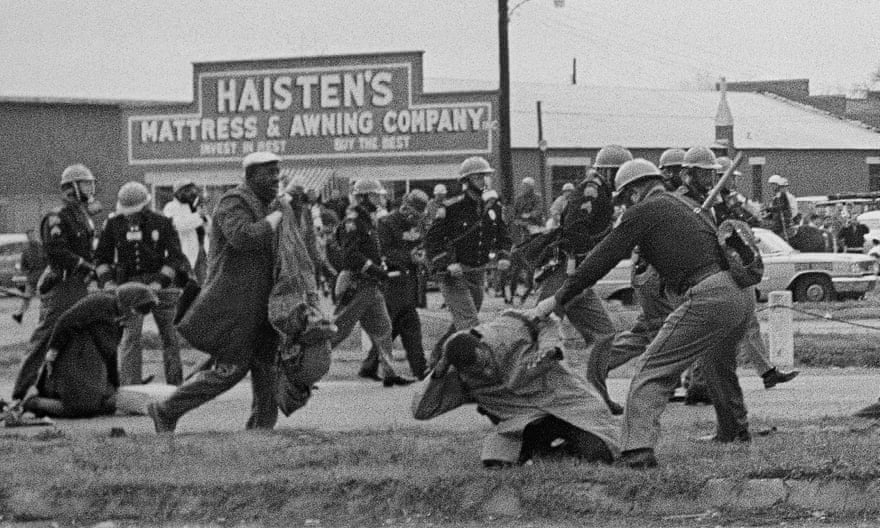

In March 1965, ABC interrupted a showing of its Sunday-night movie – Judgment at Nuremberg, a courtroom drama about Nazi war crimes – to show shocking footage from Selma, Alabama, where mostly Black protesters were being beaten bloody by mounted police with billy clubs as they tried to cross Edmund Pettus bridge into the city, demanding the right to vote.

John Lewis, then just 25 years old, led the way. “I can’t count the number of marches I have participated in in my lifetime, but there was something peculiar about this one,” he wrote in his memoir, Walking With the Wind. “It was more than disciplined. It was somber and subdued, almost like a funeral procession.”

When they reached the crest of the bridge, they were faced with the full force of Alabama’s police. After a brief standoff, the troopers charged. Lewis recalled “the clunk of the troopers’ heavy boots, the whoops of rebel yells from the white onlookers, the clip-clop of horses’ hooves hitting the hard asphalt of the highway, the voice of a woman shouting, “Get ’em! Get the niggers.” A few months later, the Voting Rights Act was passed, outlawing racial discrimination at the polls.

Lewis died in July this year, after more than three decades in Congress. On the wall of his congressional office in Georgia hung a poster from that period, showing a Black hand with a pen set against the backdrop of cotton fields, and the words: “Hands that pick cotton can pick our public officials – register and vote.” That was precisely what the segregationists were keen to prevent.

Donald Trump was the only living president not to attend Lewis’s funeral (apart from Jimmy Carter who, at 95 years old, did not attend, but sent a letter). Shortly after he won in 2016, the then president-elect thanked African Americans – for not voting in large numbers. “The African American community was great to us,” he told a crowd in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “They came through, big league. Big league. And frankly, if they had any doubt, they didn’t vote, and that was almost as good, because a lot of people didn’t show up, because they felt good about me.”

This time around, Trump was not so smug. By the morning after the election, it became clear that the presidency would be decided by the votes still being counted in big cities in key states: Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Detroit, Atlanta, Phoenix and Las Vegas. White people are a minority in all of them. In Atlanta and Detroit, African Americans are a majority; in Milwaukee and Philadelphia, they outnumber white people.

State troopers beat civil rights protesters in Selma, Alabama on 7 March 1965. Photograph: Unknown/AP

According to Trump, these votes were illegitimate by dint of where they were cast. “Detroit and Philadelphia are known as two of the most corrupt political places anywhere in our country – easily,” he said. “They cannot be responsible for engineering the outcome of a presidential race.”

This was a new twist in the racial logic of the American right, which has gone from blocking Black people from voting to allowing them to vote as long as their votes don’t all get counted.

It is important to remember that the US was a slave state for more than 200 years – and an apartheid state, after the abolition of slavery, for another century. Throughout that time, in certain parts of the country, all Black votes were, by definition, illegal, and conservatives worked hard to keep it that way. It has only been a nonracial democracy for 55 years. And that short reign now hangs in the balance.

In 2013, just a year after turnout rates for Black voters surpassed that for white voters for the first time, the supreme court gutted the Voting Rights Act, which provided some legal protections for Black voters in places where they had once been excluded.

Lewis’s home state of Georgia soon got to work thwarting the Black vote with weapons more subtle than teargas and billy clubs. The state cut the number of polling stations by almost 10%, purged tens of thousands of voters from the rolls simply because they had not voted for a while, and suspended the registrations of another 50,000 people – mostly Black – for discrepancies as minor as omitting a hyphen in their name. Those long lines we witnessed around the election were not simply voter enthusiasm – they were also voter suppression.

The trouble is that as white people become a minority in the US, efforts to disfranchise non-white voters necessarily become ever more crude and ever more desperate, but cannot be guaranteed to produce results. The sums just don’t add up. The group sought for exclusion is growing at a faster rate than can plausibly be excluded. Republicans have only won the popular vote once in the last eight presidential elections. This, in no small part, explains the bizarre moment we find ourselves in, with many Republicans refusing to admit what everyone else can plainly see – that they lost the election. They are howling at the moon because they are running out of options here on Earth.

Notwithstanding a recount, Georgia, which has seen a 24% increase in minorities over the past 20 years, voted Democrat this year for the first time since 1992. It was Clayton County, in John Lewis’s constituency, that provided the votes to put Joe Biden over the top.

The polarisation that has been intensifying over previous decades has been described as a portent of the US’s second civil war. Two antagonistic and apparently irreconcilable ideological camps, armed with different information gleaned from different sources and caffeinated by social media, have constructed entirely different understandings of everything from the climate crisis to coronavirus.

This year’s election exemplified that. The White House may change hands, but very few people changed their minds. In 2016, Donald Trump won 23 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties that had previously voted for Barack Obama; Joe Biden won back just two. In Georgia, nine of the state’s 159 counties switched party allegiance in 2016; this year it was just one. Almost half of those were won with more than 70% of the vote; in 2012, it was less than a third. Republicans and Democrats persuaded relatively few voters of their case; they just rallied their bases more effectively.

But viewed through the lens of this summer’s Black Lives Matter rebellions and the US’s changing demographics, this moment is better understood as the death throes of the first civil war than the birth of a second.

For while the American civil war, fought between the north and the Confederate south between 1861 and 1865, ended with a military victory for the north, politically it ended in a draw. It abolished slavery, but it didn’t deliver equality.

The contradictions were clear from the outset. Just 10 days after Confederate general Robert E Lee surrendered to Ulysses Grant at Appomattox, Frederick Douglass argued: “ has been called by a great many names, and it will call itself by yet another name; and you and I and all of us had better wait and see what new form this old monster will assume, in what new skin this old snake will come forth next.”

African Americans in Wilcox County, Alabama, able to vote for the first time in 1965. Photograph: Bettmann/Getty

He would find out soon enough. For a few short years after the civil war, in what is called the Reconstruction era, civil rights were enforced in the south and the suffrage of freed slaves enabled and protected. Between 1870 and 1876, Mississippi had two Black senators, South Carolina elected six Black congressmen and Louisiana briefly had a Black governor. But this experiment with equality was quickly wound up – thanks in part to a deal to settle the contested presidential election of 1876. To avert a constitutional crisis, African Americans were sacrificed on the altar of bipartisan “national unity”: federal troops were withdrawn from the south, and the individual states pursued their policies of segregation for another century.

The civil rights movement partly addressed that betrayal. But with the best will in the world, the legacy of those three centuries could not be extinguished in six decades. And that will has been lacking. Once racial discrimination was banned by law, many Americans persuaded themselves that racial equality existed in reality; they have been in flight from history. That history is now catching up with them. “There was the negative abolition of slavery: the breaking of chains,” the Black activist and intellectual Angela Davis once explained to me. “But freedom is much more than just the abolition of slavery. What would it have meant to provide economic security to everyone who had been enslaved; to have brought about the participation in governance and politics and access to education? That didn’t happen. We are still confronted by the failure of the affirmative side of abolition all these years later.”

Does that not leave Black politics stuck in the 19th century? I asked her. “The problem is that we [as a country] haven’t moved on,” she replied. “Certainly it’s important to recognise the victories that have been won. Racism is not exactly the same now as it was then. But there were issues that were never addressed, and now present themselves in different manifestations today. You only move on if you resolve these issues. It took 100 years to get the right to vote.”

Both the battle lines and the nature of the battle itself have changed. It is no longer a matter of north versus south. According to most surveys, most of the cities where Black Americans most like to live are in the south – Atlanta, the DC area, Dallas, Charlotte. According to the census, the most segregated major cities are in the north – Milwaukee, Detroit, Buffalo, Chicago. And it is not just about Black and white – the largest minority in the country is now Latino; the fastest growing is Asian-American.

Activists drive past an early voting location at the end of a Parade to the Polls event on 3 November in New Orleans. Photograph: Rusty Costanza/AP

Given the fissile nature of this moment, political violence is always lurking, and occasionally pounces. There were clashes this weekend between Trump supporters and their opponents in Washington DC; shortly after the election, police in Philadelphia received a tipoff that an armed group was arriving with the intention of disrupting the count. Two men have been charged with weapons violations. But the nature of this battle is not military; it is political and, to some extent, legal. It is the unfinished business of securing the fruits of freedom of full citizenship for all Americans.

The attachment to the Confederate flag and the antagonism over the statues of southern generals are just the most potent symbols of the roots of the conflict. But what remains is the basic architecture of a nation that has systemically excluded people on grounds of race. The Pulitzer prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson compares the US to an old house built on shaky foundations and in desperate need of repair. “Like other old houses,” she writes in her new book, Caste, “America has an unseen skeleton, a caste system that is as central to its operation as are the studs and joists that we cannot see in the physical buildings we call home. Caste is the infrastructure of our divisions. It is the architecture of human hierarchy, the subconscious code of instructions for maintaining a 400-year-old social order … We are the heirs of whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars, but they are ours to deal with.”

What is new is that the dominant race will become a minority by 2045; right now, less than half of all American children under the age of 15 are white. In five states (California, Texas, Hawaii, New Mexico and Nevada) white people are already a minority. Maryland is poised to tip that way any year now. Arizona, Florida, Georgia and New Jersey should be there by the end of the decade. To the extent that this election, and the past four years, have revolved around identity politics, the primary identity concerned has been whiteness: its anxieties, rage, capacity for empathy and solidarity.

Maybe it was Barack Obama that tipped white America over the edge? Nothing embodied the future some feared more than the son of a Muslim African immigrant father and a white globetrotting mother. In his new book, A Promised Land, Obama considers Donald Trump’s victory a racialised response to his presidency. Trump “promised an elixir for the racial anxiety” of “millions of Americans spooked by a black man in the White House,” Obama writes. “It was as if my very presence in the White House had triggered a deep-seated panic. A sense that the natural order had been disrupted. Which is exactly what Donald Trump understood when he started peddling assertions that I had not been born in the United States and was thus an illegitimate president.”

But white political identity had been heading in that direction for decades before Obama. The rise of the new right fractured the old Democrat base, peeling off what we would now call “white working class” voters for the GOP. When the veteran pollster Stanley Greenberg went to Michigan in the 80s to investigate the “Reagan Democrats” who had switched from the Democrats, he reported that in his focus groups, “these white Democratic defectors express a profound distaste for blacks, a sentiment that pervades almost everything they think about government and politics.” After he read them a statement by Robert Kennedy about racial inequality, one participant said: “No wonder they killed him.”

“That stopped me and led to a whole new analysis of Reagan Democrats,” Greenberg wrote in a 2013 report, Inside the GOP. “I realised that in trying to reach this group of people, race is everything.”

Thirty years later Greenberg observed that the fixation had remained intact, even as it had evolved. “[White Republicans] are acutely racially conscious,” he told me, referring to a focus group he conducted a year after Obama’s re-election. “They are very aware that they are white in a country that is becoming increasingly minority.”

Black voters in Harlem, New York in 1926. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

We cannot explain Trump’s rise or fall purely through the country’s racial history. The world in general, and this moment in particular, is too complex for that. But it is not possible to understand it outside that history.

Much has been made already of exit polls signalling a shift towards Trump among racial minorities and away from him among white people. Even though polling did not deliver a brilliant performance this year, there is no reason to doubt Trump may have improved his numbers among minority voters: he made an aggressive pitch for them, and he was also starting from such a low base the only way was up.

But the broader trajectory is clear and undeniable. Black and Latino voters overwhelmingly favoured the Democrats: without their huge margins in key states, Biden could not have won. In the rust belt states, where the minority population has remained fairly stable, Democrats are increasingly dependent on concentrated votes in major cities and suburbs, which are becoming more multiracial. Without Detroit, the party would lose in Michigan; without Philadelphia, it would lose in Pennsylvania. Elsewhere in the south and the west, migration is helping turn reliably Republican states into tight contests. Through the 70s and 80s, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada and Arizona were all safe Republican states. The first two are now reliably Democrat, the second two are swing states that have been called for Biden. According to the census in the past 20 years their Latino populations have increased by between 17% and 48%. That is not a coincidence.

There is nothing inevitable about any of this. Demography is not destiny. White people have long been a minority in Texas and yet, despite considerable Democrat efforts, Republicans have held that state easily since 1976. Florida is also very diverse, and yet continues to prove mostly elusive for Democrats. Meanwhile, the whitest states in the country, Vermont and Maine, are reliably Democrat.

The margins in many of the states Democrats won were tiny. Biden took Arizona, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Georgia by just 1% or less. A small swing in just a few places would have put Trump back in the White House.

Republicans have been worrying about this demographic shift for a long time. More than a decade before Trump, party grandees were warning that the GOP needed to move away from the path first blazed by Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy”, which aimed to unify southern and suburban white people with coded racist messages. “You have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks,” Nixon told his chief of staff, Bob Haldemann. “The key is to devise a system that recognises that, while not appearing to.”

That worked for much of the late 20th century, but in the past 20 years, the Republican party’s dependence on white voters has started to become a major liability. Back in 2012, the Republican consultant Ana Navarro told the Los Angeles Times: “Where [Mitt Romney’s] numbers are [with Latinos] right now, we should be pressing the panic button.” George W Bush started to shift the Republicans towards becoming a multiracial rightwing party, with less emphasis on Confederate nostalgia and more on religion, aspiration and entrepreneurship. Of course, there is nothing about the politics of diversity in itself that cannot be accommodated within a neoliberal agenda. George W Bush had the most racially diverse cabinet in history at the time (as does Boris Johnson in Britain).

Without that shift, it was believed, they were destined to obsolescence. As the South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham said at the Republican convention in 2012: “The demographics race we’re losing badly. We’re not generating enough angry white guys to stay in business for the long term.”

Trump defied that orthodoxy, doubling down on white supremacy, racist rhetoric and voter suppression. His 2016 victory, and his impressive showing this time, indicates that Republicans can stay in business with bigotry for the medium term. But its days are numbered. And in order to remain relevant, it must become ever more shrill, crude, discriminatory and exclusionary. Trump’s appeal is better understood not as a departure from the US’s racial politics, but as an intensification of it: bitter white whine in a new orange bottle. It is not yet clear whether the Republicans have an addiction problem.

In 1981 the late Lee Atwater, one-time chair of the Republican National Committee and member of the Reagan administration, explained the evolution of the party’s racial messaging. “You start out in 1954 [the year segregation was outlawed] by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger’. By 1968 you can’t say ‘nigger’ – that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing states’ rights. You’re getting so abstract now you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a by product of them is blacks get hurt worse than whites … obviously sitting around saying, ‘We want to cut this’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘nigger, nigger’.”

What Trump showed was that a significant section of white America was not as squeamish as Atwater had thought. You could just say it. And even if some of them didn’t like it, they’d vote for you anyway.

Electorally, Trumpism may prove fragile as the racial composition of the electorate continues to change. But, having matched Mitt Romney’s vote share and far exceeded John McCain’s, what this election has made clear is that, even when witnessed in all its deranged, bigoted, incompetent anomie, Trumpism remains electorally competitive and politically viable. It may not have the numbers to govern nationally, but it has the reach to disrupt and obstruct governance. The Democrats may have defeated him; but they cannot ignore what he represents.

In the 100th anniversary year of the Emancipation Declaration, which formally freed the slaves, Martin Luther King made his most famous speech. The part that is most remembered is “I have a dream” refrain. But there was another section that received a big cheer that day.

“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a cheque,” King told the March on Washington on 28 August 1963. “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the constitution and the Declaration of Independence they were signing a promissory that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note … Instead of honouring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad cheque, a cheque which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds’.”

As the late Jack O’Dell, who worked with King for many years, once told me, the way the speech is remembered matters. “So long as it’s only known as the dream speech, then it’s reduced to nothing more than a vision,” he said. “The section about the bad cheque makes it an indictment of the country that isn’t just about a dream any more. So they just stopped talking about that part.”

Fifty years later, while Black America was still waiting for that cheque to be honoured, the supreme court ruled 5-4 to gut the Voting Rights Act in June 2013. Arguing before the court, attorney Bert Rein opposed the Voting Rights Act, and referred to racially motivated voter suppression as though it were extinct: “There is an old disease, and that disease is cured. That problem is solved.” Southern states, with histories of recent racist atrocities, were now free from federal oversight. Within hours of the ruling, Texas and Mississippi announced their intention to introduce voter ID laws that have the effect of excluding some poor, young and minority voters.

Back in Georgia in 2020, the man responsible for purging its voter rolls ran for governor. He won by 54,723 votes, against Stacey Abrams, the African American woman credited with delivering Georgia for Biden. An analysis of Georgia’s June primaries by Stanford University political science professor Jonathan Rodden revealed that the average wait time after 7pm across Georgia was 51 minutes in polling places that were 90% or more non-white, but only six minutes in polling places that were 90% white.

Former Member of Georgia House of Representatives and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams. Photograph: Elijah Nouvelage/AFP/Getty Images

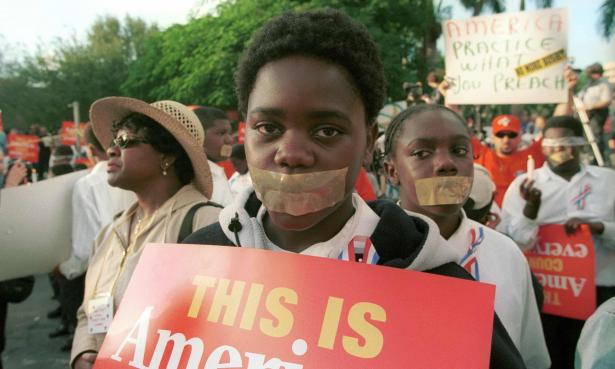

The fact that conservatives have been taking an axe to what might be understood as the second Reconstruction has not gone unchallenged. A month after the supreme court overturned key provisions in the Voting Rights Act, having been told that racism was “cured”, George Zimmerman was acquitted for murdering the unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin and the slogan #BlackLivesMatter was born.

The eruptions this summer brought the legacy of racial injustice to centre stage, locating the killing of George Floyd in a historical context in which Black lives have long been dispensable. “Part of the reason these are systemic inequalities is that they transcend not only party, but time,” Abrams told the New York Times during the demonstrations. “We have to be very intentional about saying this is not about one moment or one murder – but the entire infrastructure of justice.”

These moments stretched into autumn – with unrest in Philadelphia just a week before election day. This not only had an impact on how people voted – if exit polls are to believed, more voters said “racial inequality” was their most important issue than said coronavirus. Other data suggests that a surge in Democrat voter registration followed the BLM protests – which were remarkable in part because of the large number of white people and Latinos who participated. Just like during the civil war and the civil rights era, it is not just Black people who want to move beyond the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

Appeals for national unity in a moment of such bitter division ring hollow unless they spell out on what basis, and to what end, one intends to unite. The US has been down this road before, at the end of Reconstruction. Arguably, we are still on it. “If war among the whites brought peace and liberty to the blacks,” said Frederick Douglass shortly before the end of Reconstruction, “What will peace among the whites bring?”

This is not the first time the US has found itself with a new president right in the midst of a period of racial upheaval, and with a protest movement capturing the national imagination in the face of opponents who want to turn back the clock. When Lyndon Johnson sat down with his key advisers, on the evening of John F Kennedy’s funeral, to discuss his maiden speech to Congress, they all pleaded with the newly sworn-in president not to focus on civil rights – since there was little prospect of success. “The presidency has only a certain amount of coinage to expend, and you oughtn’t to expend it on this,” said one.

“Well,” Johnson replied, “what the hell’s the presidency for?”

Joe Biden might well ask himself the same question.

Gary Andrew Younge FAcSS is a British journalist, author, and broadcaster. He was editor-at-large for The Guardian newspaper. In November 2019, it was announced that Younge has been appointed as professor of sociology at the University of Manchester. A new edition of his book Who Are We? How Identity Politics Took Over the World was published by Penguin in September.

Support The Guardian. Progressive journalism powered by you,

With two innovative apps and ad-free reading, a digital subscription gives you the richest experience of Guardian journalism. It also sustains the independent reporting you love.

Spread the word