The recovery from the deep economic nosedive of last spring continues to lose steam, the latest jobs report shows. Job growth slowed further in November, long-term unemployment (27 weeks or more) kept rising, and, as in past recoveries, jobs are returning more slowly for Black and Hispanic workers than for white workers in a still-depressed job market. To relieve hardship and promote a strong recovery, policymakers should enact a stimulus package before the end of the year that, among other things, prevents millions of unemployed workers from running out of unemployment benefits right after Christmas.

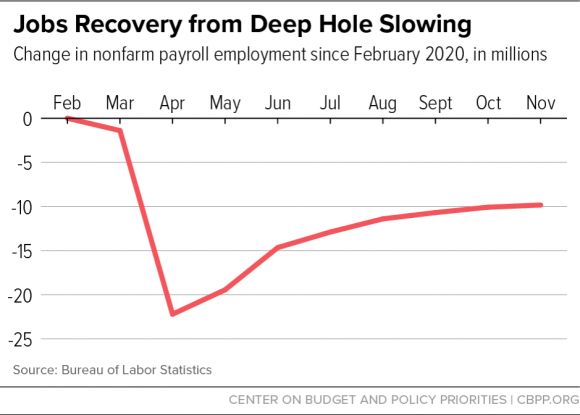

Payroll employment barely halfway back to pre-crisis level. Nonfarm payroll employment rose by 245,000 jobs in November — the fifth straight month of shrinking job gains — and is still 9.8 million jobs (6.5 percent) lower than when the recession started in February. Private employment rose by 344,000 jobs but remains 6.6 percent below February’s level. State and local government employment is 1.3 million jobs below its February level, with 1.0 million of those job losses in education.

Millions in danger of running out of unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. The number of people who have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks — the maximum duration of regular state UI benefits in most states — has risen from 1.1 million in February to 3.9 million in November. Two-thirds of the Labor Department’s reported number of UI recipients are in temporary programs created by the CARES Act of March that expire right after Christmas. They include people who have exhausted their regular state UI benefits and are getting up to 13 weeks of federally funded Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation and people who have lost their jobs and don’t qualify for regular state benefits but are receiving federal benefits under the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program. Unless Congress acts, these programs will pay their last benefits for the week ending December 26.

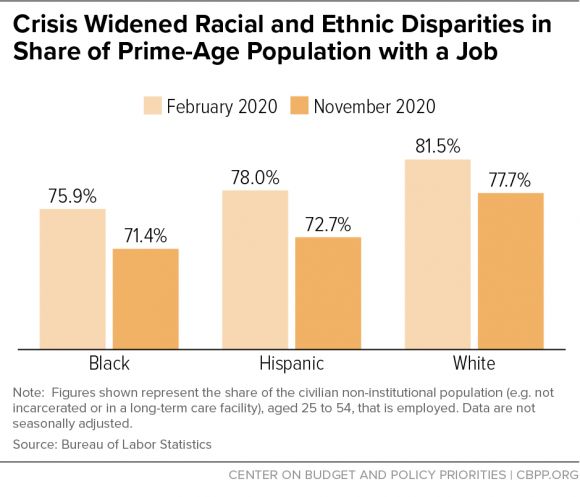

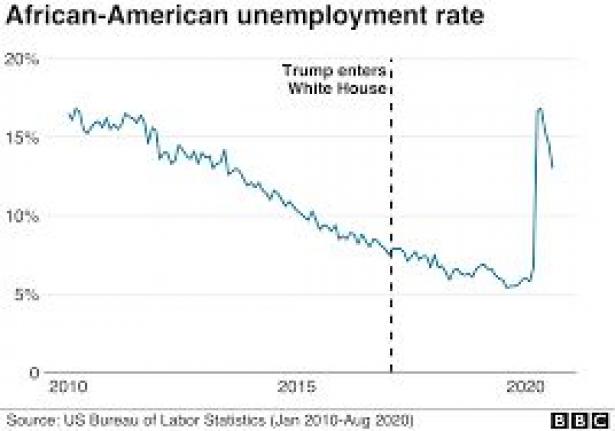

Large racial and ethnic disparities in employment persist. The official unemployment rate, which spiked to 14.7 percent in April, was a still-elevated 6.7 percent in November. Black and Hispanic unemployment rates, while remaining higher than white rates, fell to historically low levels before the crisis of early this year. Unemployment rose sharply for all groups in the recession and remained high in November, but the Black and Hispanic unemployment rates (at 10.3 and 8.4 percent, respectively) were 4.5 and 4.0 percentage points higher in November than in February, while the white rate (at 5.9 percent) was a lesser 2.8 percentage points higher.

These patterns have endured in recessions and recoveries alike and are rooted in this nation’s history of structural racism, which curtails job opportunities for Black people through policies and practices such as unequal school funding, mass incarceration, and hiring discrimination. Black workers tend to be “the last hired and first fired.” High unemployment rates for Hispanic people, which also consistently exceed the white rate, reflect many of the same barriers to opportunity.

The unemployment rate is an incomplete measure of joblessness because it only includes people who are actively looking for work (or have been laid off but are subject to recall to their former jobs). It doesn’t include people who want a job but haven’t been looking due to the lack of job opportunities. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio — which measures the share of the population aged 25-54 with a job — doesn’t have that shortcoming, and it tells a similar story of large, continuing racial disparities. The employment-to-population ratio was lower for Black and Hispanic workers than for white workers when the recession started and has fallen more for them since. In November, the Black employment-to-population ratio was 4.5 percentage points lower than in February, the Hispanic rate was 5.3 points lower, and the white rate was 3.8 points lower.

More stimulus needed now. With the economy still in a deep hole, policymakers face an imperative to enact a relief and stimulus package quickly to support the recovery and ensure that millions of UI recipients don’t lose their benefits in the coming weeks.

Chad Stone is Chief Economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, where he specializes in the economic analysis of budget and policy issues.

He was the acting executive director of the Joint Economic Committee of the Congress in 2007 and before that staff director and chief economist for the Democratic staff of the committee from 2002 to 2006. He was chief economist for the Senate Budget Committee in 2001-02 and a senior economist and then chief economist at the President’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1996 to 2001.

Stone has been a senior researcher at the Urban Institute and taught for several years at Swarthmore College. His other congressional experience includes two previous stints with the Joint Economic Committee and a year as chief economist at the House Science Committee. He has also worked at the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Office of Management and Budget. Stone is co-author, with Isabel Sawhill, of Economic Policy in the Reagan Years. He holds a B.A. from Swarthmore College and a Ph.D. in economics from Yale University.

You can follow Chad on Twitter @ChadCBPP.

Click HERE to support the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Spread the word