There was no direct connection between the “Central Park Karen” incident in New York City and the police killing of 46-year-old George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, beyond the coincidence of timing. Time in the pandemic has been elastic and confusing, and reports of the separate incidents did not emerge immediately, but the two events occurred on Monday 25 May, Memorial Day.

The video footage of the two incidents loomed over the strange, violent summer of coronavirus and civil unrest as a kind of digital diptych representing the state of racism – and whiteness – in America in 2020.

On one side we had Floyd being slowly and mercilessly suffocated to death beneath the knee of the white male police officer Derek Chauvin, a brutal portrait of the implacable indifference to Black life that defines American policing. On the other side was the 40-year-old white investment manager and scofflaw dog-owner Amy Cooper, an avatar for the respectable white civilian who demands that violence be brought to bear on her behalf because a Black man has dared to expect her to abide by the rules governing public space.

The specter of Karen persisted as Black Lives Matter protests and civil unrest spread around the country following Floyd’s murder and reckonings with racism began to roil institutions, toppling careers as well as statues. More than just an amusing meme, Karen allowed for a new kind of discourse about racism to gain credence in the US.

“We as a culture have adopted this stance that white women are more virtuous and not complicit in upholding racism in particular,” said Apryl Williams, a professor of communication and media at the University of Michigan. “They just sort of go along with it, but they’re not conscious actors. The Karen meme says, no, they are conscious actors. These are deliberate actions. They are complicit. And I think that’s why it strikes a nerve with people.”

Amy Cooper’s Karen status was cemented when she called the police on Christian Cooper, a 57-year-old Black birdwatcher, after he had asked her to leash her dog in New York City’s Central Park. Not content with falsely alleging, twice, that “an African American man” was “threatening me and my dog”, Cooper put on a play for the 911 operator, changing the register of her voice to one of distress and panic as she cried: “I am being threatened by a man in the Ramble. Please send the cops immediately.”

It was through that performance that Amy Cooper took on the mantle of an American archetype: the white woman who weaponizes her vulnerability to exact violence upon a Black man. In history, she is Carolyn Bryant, the adult white woman whose complaint about a 14-year-old Emmett Till led to his torture and murder at the hands of racist white adults. In literature, she is Scarlett O’Hara sending her husband out to join a KKK lynching party or Mayella Ewell testifying under oath that a Black man who had helped her had raped her. In 2020, she is simply Karen.

Williams defines a Karen as a “white woman surveilling and patrolling Black people in public spaces and then calling the police on them for random, non-illegal infractions”. She has been studying memes about Karen and her predecessors (BBQ Becky, Permit Patty, Pool Patrol Paula, etc) for several years, and in in the journal Social Media and Society, she traces Karen’s historical lineage and makes the case for her societal importance.

“In the past, Black bodies were controlled in public spaces by threats of violence, lynching, and routine, targeted racialized terror that dictated who Black people could speak to, where they were allowed to live, and in which spaces they were able to exist,” she writes. “Presently, the routine act of calling the police on Black people in public spaces extends this historical practice of regulating Black bodies to maintain White supremacist order.”

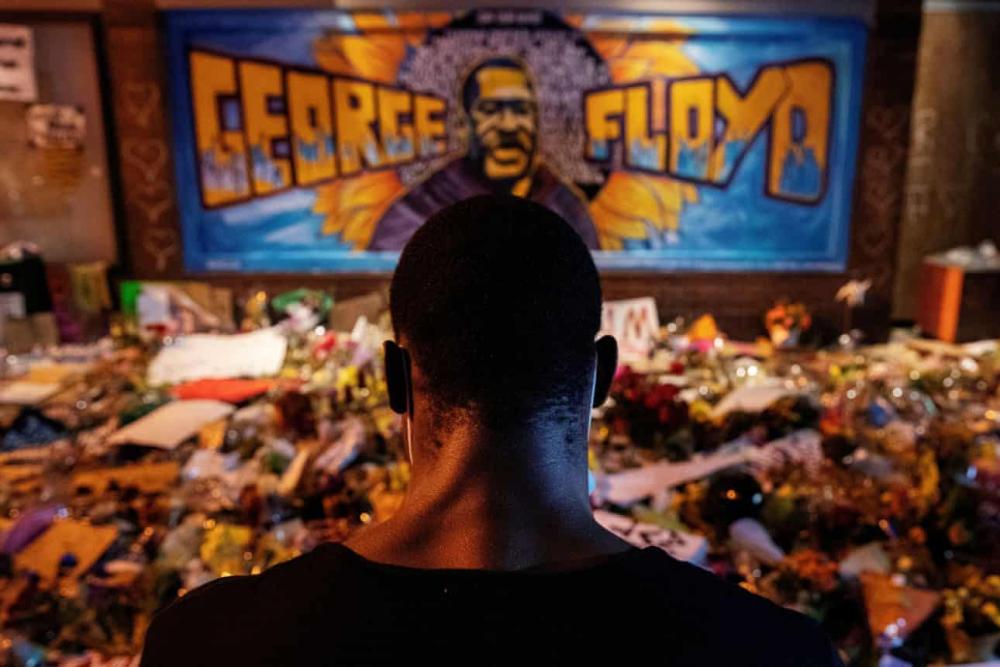

Photograph: Lucas Jackson/Reuters // The Guardian

According to Williams, “Becky”, or “BBQ Becky” – the name given to a white woman who called the police on a group of Black people for using a charcoal grill in Oakland, California – was the more common moniker for that kind of white woman before the coronavirus pandemic, when Karen took off. But the name is not as important as what it signifies. “It’s a cultural shorthand and it’s interchangeable with any number of names,” Williams said. “If my friend were to call me and say, ‘I had an incident with a woman today at the bank and it was a Susan,’ she wouldn’t have to say anything else. I would say, ‘What did Susan do?’ and I already know what’s coming.

“This is a continuation of a historical legacy,” she added. “We can trace it back to the Reconstruction period when vigilante groups were assembled to patrol freed slaves … These Karens and Beckys are still serving as that sort of extra-legal patrolling. They aren’t actually part of the law, but they act as enforcers of it. They extend the legal power, even though they have no legal power.”

To live in the United States is to experience the passage of time through the litany of names of Black people murdered or beaten by the state. In my own lifetime, I can chart a course from Rodney King to Amadou Diallo to Oscar Grant, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, and George Floyd.

Much of the civic response to the uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore focused on broad systemic racism and reform. Police body cameras were sold as a panacea. Implicit bias offered both an explanation and a justification for actions that, to those affected by them, still felt like plain old racism. It’s not intentional, the story went; every white person must still be granted the benefit of the doubt, the assumption of perpetual racial innocence.

But as the summer of Karen kicked off, it became clear that people of color in America, and especially Black people, were no longer prepared to accept the alibi offered by unconscious bias. Among the first to rip off the Band-Aid was the Glee actor Samantha Ware, who responded to her former co-worker Lea Michele’s platitudes about Floyd’s murder with a reminder of how the star had treated her: “Remember when you made my first television gig a living hell?!?! Cause I’ll never forget.”

Soon, social media feeds began to fill again with testimonials of abuse from people of color, not so much #MeToo as #YouToo. You, too, have been racist, the moment of reckoning warned, and your co-workers and underlings are not going to keep your secrets for you any more.

It would be silly to chalk up the entire racial reckoning of 2020 to the power of Karen memes, but it would also be silly to dismiss their influence. Williams compares it to that of the Black press. Events that would otherwise be ignored – a white woman in San Francisco calling the cops on a man chalking “Black Lives Matter” on his building, say – became fodder national news once they fit within the memetic frame of Karen.

“Becky and Karen memes provide a vital social function,” Williams writes. “They restore agency to Black communities by allowing them to exert a form of justice on perpetrators. In a subversion and reversal of power dynamics, Black meme creators police White supremacy and explicitly call for consequences.”

Of course, any attempt by Black people to assert power against white supremacy is instantly met by a backlash, and the backlash against Karen memes was practically foreordained. Complaints about Karen being sexist were noteworthy mostly for how neatly they re-enacted the Karen dynamic. Confronted with evidence of their own agency and complicity, some white women responded by reasserting their victimhood.

What I’ve found especially useful about Karen memes is the way they’ve given willing white women a tool with which to assess their own behavior and, if they want, improve it. My own mother, who is white, has on rare occasions demonstrated behavior that verged on the Karen-esque. This summer, for the first time, she acknowledged some of those Karen tendencies to me and stated her intention not to act like that any more – a conversation I’m not sure we would have had absent the meme.

Williams recalled similar conversations with white friends, and offered three simple rules to avoid being a Karen. One: recognize the privilege and history of being a white woman in this society. Two: avoid calling the police on people of color unless someone is in imminent danger of harm. And three: “Understand that it’s just not always about you, period. People are not out to get you for the most part, people are not trying to hurt you or harm your property or make you uncomfortable,” she said. “You’re not that special, Karen. You’re not that special.”

[Julia Carrie Wong is a technology reporter for Guardian US, based in San Francisco. Click here for Julia's public key. Twitter @julliacarriew]

Spread the word