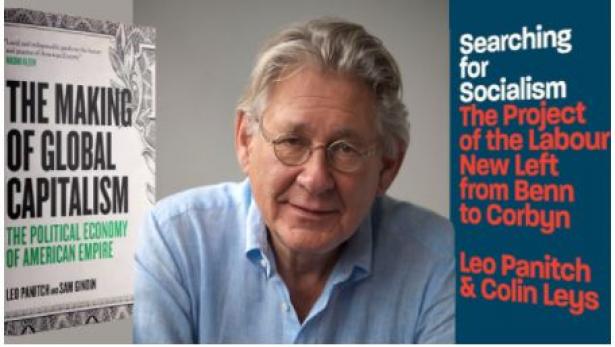

It’s taken far too long time for me to write this. Many others who knew Leo Panitch – professor political science at York University in Toronto, longtime co-editor of the Socialist Register, and author of many important essays and books – for a longer period than I did and/or saw him more regularly than I did were able to write memorials to him fairly quickly. I couldn’t. For whatever reason, when Leo died suddenly on December 19th last year – of COVID-19, of all things! In the Toronto hospital he went to for cancer treatment! – I couldn’t get over the shock. The last year has been utterly hellish but for Leo to suddenly not be in it anymore…I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t. It doesn’t make sense.

I first met Leo in late 1998 when he was teaching a course on capitalist globalization at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Besides being one of the most compelling speakers on the left that I’ve ever heard – not a small matter, as too many professors and socialists and socialist professors really don’t know how to keep an audience’s interest – he was a fun guy. Utterly charming. And he listened to his students. Leo and I were two out of maybe four Marxists in the course – this was the late 1990s, after all, and the dissolution of the USSR ensured that Marxism was no longer “hip” within the academy (to the degree that it ever was). This never visibly bothered Leo. After all, he’d been spending a great deal of time writing essays interrogating “The Impoverishment of State Theory” in an era where so many social scientists were claiming that capitalist globalization had made states irrelevant, powerless, etc.

Not only was this all nonsense but it forced the Marxist debates from the 1970s on capitalism and the state down the memory hole. Ralph Miliband, Nicos Poulantzas, Fred Block, Joachim Hirsch… wait, who were they again? One had to be patient while constantly fighting against the marginalization of Marxist state theory, so it was no big difficulty for Leo to engage his Grad Center students without any hint of frustration, despite most of them ranging from moderately social-democratic to outright conservative.

Others have already eloquently described Leo’s contributions to Marxist political economy and socialist political strategy. I won’t write a variation of that here. I will say that I agreed with him most of the time. Not always, though. While in most respects I was already a “Ralph Milibandite” by the time I met Leo (though he’d sometimes rib me for sounding a bit too “quasi-Trotskyist” for his taste – guilty as charged, I guess), I made clear where I found flaws in Miliband’s work. Leo had no problem with this, as we had no serious differences in terms of what socialist politics should consist of from day to day, even if there were things left unsaid in his writings on strategy that I considered important. And when I told him this, he took it in stride and even responded with commentary along the lines of “fair points.”

Furthermore, despite being – unlike Leo – a “monocausal” Marxist who is convinced that the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as capital investment grows more quickly than labor is the underlying reason for all capitalist crises, I agreed with, or at least was highly informed by, most of what Leo and Sam Gindin wrote in their magnum opus, The Making of Global Capitalism (Verso Books, 2012). In retrospect, Leo and Sam may have been too sanguine that a new era of inter-imperialist rivalry was unlikely to come; the current relationship between the U.S. and China, despite how intertwined our national economies remain, sure looks Cold War-ish to me. But Leo was certainly right that “Communist” China had become an integral part of global capitalism. And while he probably was never familiar with the key writings of the admittedly U.S.-centered tradition of “Third Camp” Marxism, and may have never even heard the term “bureaucratic collectivism,” Leo never believed that the USSR or its Eastern European buffer states were innately more progressive than the capitalist West nor did he ever have any use for Third Worldist romanticism about the Chinese or Cuban Communist Parties. If his understanding of Lenin was often too close to what Lars Lih calls the “textbook interpretation,” there was never a hint of Stalinist influence in his political views – which was far more important.

Contrary to what some have said, Leo never claimed that the “era of revolutions” had permanently “passed,” or that the transition to socialism wouldn’t involve “rupture.” He was no “evolutionary socialist.” Yes, he believed that the transition to socialism would differ considerably from the “1917 model” of revolution where workers’ councils, outside the existing state, suddenly emerge and provide a ready-made replacement for said state after an armed insurrection has concluded. But as Steve Maher writes, “Leo didn’t just wave the banner of socialist revolution. He actually meant it.” No parliamentary cretin, to use Marx’s phrase, would say this:

“The left’s tendency is to try to respond to neo-classical economists by saying the state is efficient. This has really been a terrible response and has really created enormous confusion. The left’s response cannot be statist. It has to speak to people in terms of the state being responsible for globalisation rather than being a victim of it. It has to speak to people’s fear in alienation of the state and that means that it has to pick up the tradition of the Paris Commune, of that side of Marxism. Which, of course, wants to replace what is private with what is collective, but it wants to do it in a way that does not pretend that the existing state as it is now organised is correct.”

Leo Panitch was a genuine organic intellectual. He was a great teacher and a good friend. He should not have left us so soon and so suddenly. But we should all be grateful for what he gave to the left, to his students, to his comrades.

Rest in power, professor.

[Essayist Jason Schulman, an adjunct assistant professor of political science at Lehman College and John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is a sponsor of New Politics magazine. He is the editor of Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Legacy (Palgrave, 2013), and author of Neoliberal Labour Governments and the Union Response: The Politics of the End of Labourism (Palgrave, 2015). A collection of his writing from New Politics is available HERE.]

Information on New Politics, a socialist magazine, is available HERE

Spread the word