No one thought that Ethel Rosenberg would be executed. At the time of her trial in 1951, no federal judge had sentenced a woman to death in nearly a hundred years. She hadn’t been accused of murder or of being an accomplice to a murder or of conspiracy to commit a murder. These, it seems, were the only crimes for which the American government might kill a woman. Female traitors during the Second World War – Tokyo Rose, Axis Sally, the ‘Doll Woman’ – had received prison terms. And no American civilian, man or woman, had ever received the death penalty in peacetime for ‘conspiracy to commit espionage’, the official charge against her. Almost until the last moment, she expected President Eisenhower to intervene. In her letters she had called him the ‘liberator’ to millions, ‘whose name is one with glory’. Surely, in his own country, he wouldn’t permit the ‘savage destruction of a small unoffending Jewish family’. Eisenhower might indeed have preferred to save her – ‘it goes against the grain to avoid interfering in the case where a woman is to receive capital punishment,’ he told his son – but he feared that if he commuted her sentence then ‘from here on the Soviets would simply recruit their spies from among women.’ Housewives across America would abandon their children in order to rendezvous with agents on park benches; instead of making dinner they would be exchanging briefcases in the back rows of movie theatres. Mrs Rosenberg had stolen the secret of the atomic bomb and refused to admit it; she must not be allowed to corrupt American womanhood too.

When the FBI first arrested Ethel’s brother, then Ethel’s husband, then Ethel, reporters kept failing to discover anything interesting about them. Among other poor Jews on New York’s Lower East Side, the whole family had appeared to be so unremarkable that the historian John Neville would say that ‘they might have been chosen at random from the telephone directory.’ Ethel’s father, Barney Greenglass, repaired sewing machines. Her mother, Tessie, was from Galicia (now part of Ukraine), and raised their four children in a cold-water tenement apartment. Tessie was illiterate, and sympathetic to the Left, though unsophisticated: she once gave money to a door-to-door canvasser for the Nazis because a ‘national socialist’ party sounded good to her. She was envious of her clever only daughter and favoured her youngest child, David. One of Ethel’s childhood friends remembered that Tessie was ‘more bigoted than religious ... If God had meant for Ethel to have music lessons, he would have provided them. As he hadn’t there was something sinful about music lessons.’ Much of the early part of Anne Sebba’s new biography concerns Ethel’s love of Yiddish theatre and her own theatrical ambitions. She was named ‘class actress’ in a high school that produced Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz), Zero Mostel and Walter Matthau. But she was lopsided from scoliosis, and when she graduated during the Depression, considered herself fortunate to get work at the National New York Packing and Shipping Company. Men handled the boxes, while women wrote receipts. It was there she had her political awakening. She lay down in the middle of the road to stop deliveries during a strike; when she was fired, she complained to the National Labour Relations Board and got her job back, as well as lost wages. In 1936, when she was 21, she met Julius Rosenberg, an 18-year-old engineering student, when she sang at a benefit performance to raise funds for American volunteers fighting with the republicans in Spain. ‘I have loved her ever since that night, and always when I hear her sing it is like the first time,’ Julius later wrote. When his Soviet handler asked him what she was like, he ‘closed his eyes and blew a kiss into his hand’.

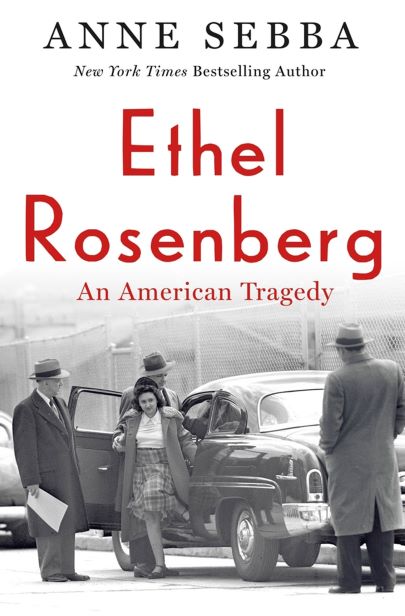

Ethel Rosenberg: A Cold War Tragedy

By Anne Sebba,

Macmillan/St. Martin’s Press; 320 pages

June 8, 2021

Hardback: $28.99

ISBN: 9781250198631

E-book, $14.99; ISBN: 9781250198655

Like Ethel, Julius had grown up on the Lower East Side. His parents were Russian-Jewish immigrants, but he was able to attend the ‘Harvard of the Jews’ – City College in upper Manhattan. It was all-male, free, had no chapel requirements and the admissions office didn’t discriminate against boys called Rosenberg. My grandfather was there at the same time, playing ping-pong between classes while everyone else was discussing radical politics. (Or so he always said. He went on to have a long career at the State Department.) Julius’s friends were other engineering students who had joined the Steinmetz Society, a discussion group affiliated with the Young Communist League. The accounts of the people who knew him then – though is it just because they know how the story ends? – emphasise his gullibility and unworldliness. Ethel’s brother David claimed that during the war Julius strode into the Russian consulate in Midtown Manhattan and announced himself: ‘He goes knocking on their door, and he says: “Look I want to be a spy for you.” What chutzpah. What craziness. He was crazy.’ Russian sources, more plausibly, suggest that Julius was recruited by Soviet intelligence in Central Park during a Labour Day rally in 1942. By then he was a junior engineer for the Army Signal Corps and married to Ethel.

In 1999, Julius’s handler, Alexander Feklisov, published his memoirs over the objections of the Russian intelligence service. He was a decorated Hero of the Russian Federation, credited in Moscow with having helped resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis: he figured they’d let him get away with it, and, if not, he was at the end of his life anyway. Sebba may be right that his ‘recollections of the Rosenbergs have to be treated with extreme caution’, or at least some scepticism, but in twenty years no one has contradicted the substance of his account, and he often writes against his own interest. He says that he had loved Julius, and is angry that Russian intelligence didn’t do enough to protect him, or to honour the help he’d given them during the war. There’s a monument to the Rosenbergs in Havana: Feklisov thought there should be monuments everywhere.

In his telling, Julius is upstanding (he refused to accept payment), reliable (Feklisov couldn’t remember him ever missing a rendezvous or being late), intelligent but insufficiently paranoid. Once, delighted to see Feklisov on a street corner, he waved to him and called out ‘Hello comrade!’ He also had to be instructed to associate less openly with party members, to stop attending rallies for the Red Army, and to cancel his subscriptions to left-wing newsletters. He was allowed to keep paying his party dues, but not under his own name. Although Feklisov says that Julius had ‘read the great classics of socialism, Marx, Engels, Lenin ... during our meetings his statements had a childish revolutionary naiveté, which was part of his personality ... “I don’t know if I’ll live long enough to see gold-plated urinals,” he would tell me. “Hey, Lenin wrote that we would have them some day, and I sincerely hope so!”’

Julius’s work inspecting electrical equipment for defence contractors gave him access to secret information about new technology, including a radio device that could distinguish between friendly and unfriendly aircraft. His ‘usual delivery’ to Feklisov was at least six hundred pages of documents every few weeks. At the end of 1944 he was able to give Feklisov a working proximity fuse, the crucial component in one of the world’s first ‘smart’ weapons, a precursor to the homing missile. (In 1960 one would help the Soviets bring down Gary Powers’s U2 plane.) Feklisov’s superiors were suspicious. The proximity fuse had cost a billion dollars to develop: you couldn’t just walk out of a factory with one. But that’s exactly what Julius did. ‘He had been able to take a proximity fuse that had been rejected and hide it in a corner of his workshop. Little by little he managed to replace the defective parts until the device was in perfect condition. Then he hid it behind a box on a shelf where spare parts were kept,’ and waited to remove it until Christmas Eve, when security was lax. Yet it was decided that Julius might be even more valuable as a handler of other spies, since as an American citizen he could move more freely than Feklisov, who had an FBI file and was often followed. (Feklisov’s official posting was as a trainee at the New York consulate: when he wasn’t running agents, he helped people with visa problems.) Feklisov considered Julius a ‘born recruiter who could communicate forcefully and passionately his boundless faith in socialist ideals’, and they quickly ‘built a whole network’ of engineers, almost all of them Julius’s former classmates from City College, now engaged in war work. At least eight men passed along technical drawings and manuals about ‘the production of new planes, artillery pieces, shells, radar and electronic calculators’. They weren’t to think of themselves as spies: the two countries were, after all, allies.

Feklisov usually met Julius, codename ‘Liberal’ or ‘Libi’, in Manhattan, sometimes in Brooklyn or the Bronx. They mostly did ‘brush passes’: Julius would hand Feklisov papers or microfilm (he learned how to use a Leica with a special lens) in overcrowded buses or in cinemas, or sometimes during boxing matches at Madison Square Garden. They’d also meet regularly for longer ‘instruction meetings’ at bars and cheap restaurants – the noisier and busier the better – where they wouldn’t carry anything incriminating.

All of this, as far as Feklisov could tell, delighted Julius. ‘Everything concerning the USSR was of interest to him.’ He wanted to know about Russian nurseries, schools, shops. As for ‘the purges, the political trials, the repression of the Stalin era’, they never discussed them, and Feklisov decided that Julius, who ‘read a lot and spoke to me about Cromwell, the French Revolution and Robespierre’ was persuaded that the violence was justified: ‘The choice was a simple one: either Nazism or us.’ The worst that Feklisov would say about Julius was that he was susceptible to flattery: he liked to be told that he was as brave as the partisans behind enemy lines in Yugoslavia or Italy. In September 1944, Julius asked for permission to recruit Ethel’s brother David Greenglass, a 22-year-old machinist. Feklisov claims he worried that David was too young – his political views might still be in flux. But when he told his superior that David’s new posting was a military installation in New Mexico, ‘my boss was unable to hide his excitement.’ Feklisov was shut out and a different intelligence officer put in charge of David’s reports. When the war ended, Feklisov was recalled to Leningrad. He told Julius to spend more time with his family: he should ‘take Ethel out on the town’.

Where had she been in all this? In Feklisov’s memoirs, Ethel hardly appears. They never met. In Sebba’s careful account, she helped Julius prepare for his engineering exams by typing his notes. She kept house, badly, because it bored her. She had headaches and back pain, probably because of her scoliosis. Her first son, Michael, was born in 1943, and seemed always to be sick. She took mothering classes and subscribed to Parents magazine. She had another baby, Robert, took guitar lessons and saw a psychoanalyst, Saul Miller, three times a week. Decades ago, one of Ethel’s previous biographers, Ilene Philipson, interviewed Miller. He told her that Ethel was attracted to analysis because she ‘believed that her problems stemmed from her family of origin’ – she was convinced that her mother hadn’t loved her. Miller said that Ethel thought of both him and Julius as her ‘saviours’: ‘intelligent, empathic men’ who ‘actively valued and respected her, and took her side in her external battles with her family’. Miller said he knew that she was a communist, but didn’t remember her ever talking about it; they certainly never discussed espionage.

After the bombing of Hiroshima, President Truman thanked Providence for giving Americans, unique among the peoples of the Earth, ‘the basic power of the universe’. Leslie Groves, who directed the Manhattan Project, told a New York audience that the Russians would never get the bomb: ‘Those people can’t even make a Jeep,’ he said to applause. In 1949, when the Soviets conducted their first nuclear test over what is now Kazakhstan, they used a plutonium-based implosion device, like the ‘Fat Man’ bomb dropped over Nagasaki. The Americans couldn’t believe that they’d come by it honestly. By decrypting Soviet diplomatic cables, the Signal Intelligence Service – later subsumed into the National Security Agency – determined that the eminent physicist Klaus Fuchs and, though far less usefully than Fuchs, David Greenglass and Julius Rosenberg, had passed on atomic secrets. The NSA was more concerned about preserving the secrecy of their operation (codenamed Venona) than in using the cables to go after Julius’s spy ring, and decrypted messages about the Rosenbergs wouldn’t be released until 1995. Some of them referred to Ethel – ‘knows about her husband’s work’ – but unlike her husband and brother she wasn’t considered important enough to have her own codename.

In January 1950, under interrogation in London, Fuchs confessed that when he’d been a senior scientist at Los Alamos, he’d passed information to the Soviet Union and had answered questions from their scientists. He either revealed the identity of the Russian agent he talked to in New Mexico or the Americans figured it out for themselves through the Venona intercepts. In any case, when a photograph of the chemist Harry Gold ran on the front page of the Herald Tribune in May – ‘US Arrests Go-Between for Soviets in the Fuchs Case’ – Julius knew the game was up. Gold had received information from David and given him money. It was a profound failure of tradecraft, Feklisov says, for the same courier to meet agents from different spy rings: ‘compartmentalisation is a basic rule of all clandestine work.’ Julius arranged for David to travel to Mexico City, where a Russian agent would meet him with passports that would allow David, his wife and their two children to go to Sweden or Switzerland, then Prague, then Moscow. But David didn’t want to live in the workers’ paradise: he liked New York. He wasn’t even entirely sure that Gold was the same man who’d been his courier – they had met only once, for less than fifteen minutes. Sebba asks why, when David didn’t leave the country, the Rosenbergs didn’t go themselves. She suggests that so far as they knew, David was the only person who could connect them with Gold and Fuchs. Since they wouldn’t have betrayed David, they assumed he wouldn’t betray them.

On the afternoon of 15 June 1950, FBI agents appeared at David’s apartment on the Lower East Side and asked if he would talk to them at their office. Before midnight a stenographer was typing his confession:

On or about 29 November 1944, my wife, Ruth, arrived in New Mexico from New York City and told me that Julius Rosenberg, my brother-in-law, had asked if I would give information on the Atomic Bomb and stated as a reason for that that we are at war with Germany and Japan and that they are the enemy and that Soviet Russia was fighting the enemy and was entitled to the information. On that basis, I agreed to give whatever information came to me in the course of my employment at Los Alamos, New Mexico, at the Los Alamos Atom Bomb Project. This message, which my wife conveyed to me, was not her own idea but was an idea given to her by Julius Rosenberg.

David later reported that the FBI agents hadn’t threatened him. They kept offering him food and coffee, and one was even Jewish. He wasn’t under arrest: he could have gone home. There was no deal on the table, though he was under the impression that if he continued to co-operate he wouldn’t be prosecuted. He didn’t think to ask for a lawyer until after he’d signed the confession – at which point he was immediately put under arrest. He asked to call Julius – ‘I wanted Julius to put up money. For bail, everything, bail, lawyer, the whole works. I was there because of Julius Rosenberg’ – but by then Julius had been arrested too. Unlike David, Julius said he was innocent, and kept saying it. Ethel told the press: ‘Neither my husband nor I have ever been communists, and we don’t know any communists. The whole thing is ridiculous.’ She was arrested three months later. FBI agents complained that she had ‘made a typical communist remonstrance’ when she asked to see Julius’s warrant and to call an attorney. They weren’t certain that she’d spied for Julius, but a memo written at the time shows that they were ‘proceeding against his wife’ so that she ‘might serve as a lever in these matters’. Also arrested was Morton Sobell, who had been at City College with Julius and then worked for General Electric, with access to information about sonar, infrared rays and missile guidance systems. He wouldn’t have been prosecuted if he hadn’t lost his nerve: after Julius’s arrest, he’d gone straight to the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City, which was under US surveillance, without first alerting Russian intelligence in New York. Before the embassy could check Sobell’s story, the CIA had arranged for Mexican police to drive him back across the border.

The trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg began on 6 March 1951 and lasted sixteen days. The syndicated columnist Inez Robb offered a warning that went out in more than a hundred newspapers: Ethel might appear too dumpy to be a spy, ‘innocuous and vacuous’, but she couldn’t disguise her ‘extremely intelligent’ eyes. Sebba thinks that ‘Ethel’s interpretation of dignity in court, possibly in an attempt to control her nerves, was to try not to smile.’ She miscalculated. For reporters, her ‘stony expression’ became evidence that she was ‘cold and unfeeling’ with a ‘contempt for the proceedings’ that was ‘barely concealed’. It also went against her that she was older than Julius and was sometimes falsely portrayed as being taller. She might have expected support from the left-wing press, but so long as the Rosenbergs refused to admit that they were communists, the party worried that helping them might backfire. The Jewish community stayed away until after the trial too. The Rosenbergs didn’t claim that there had been an antisemitic government plot to frame them, only that the FBI had in good faith been deceived by David and Ruth Greenglass. The defence presented their clients as participants in an embarrassing family drama, not the Dreyfus Affair. Some Jewish families (I suspect this may have been the case with my own) were gratified that the trial judge and the chief prosecutors were Jewish. One of them was the 24-year-old Roy Cohn, now best known as Donald Trump’s mentor in his Studio 54 days. We would clean up after ourselves.

The prosecution’s case depended almost entirely on the testimony of the Greenglasses. Ruth testified that in 1944 Julius had asked her to visit David in New Mexico and to persuade him it was in the interest of world peace that he pass on whatever he could find out about the bomb. She said she’d hesitated, but ‘Ethel Rosenberg said that I should at least tell it to David, that she felt that this was right for David, that he would want it, that I should give him the message and let him decide for himself.’ David testified that when he’d returned to New York, he’d given Julius a description of the bomb’s explosive lenses and a list of scientists assigned to the project. Although he hadn’t mentioned his sister’s involvement in his initial interviews with the FBI, he now said that Ethel had typed up his notes. Decades later, he told Sam Roberts, the author of The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case (2001), that he didn’t actually remember if it had been Ethel or his wife who had done the typing: ‘I told them a story and left her out of it, right? But my wife put her in it. So what am I going to do, call my wife a liar? My wife is my wife. I mean, I don’t sleep with my sister.’

When Julius took the stand, he testified that he was ‘in favour, heartily in favour, of our constitution and our Bill of Rights and I owe my allegiance to my country at all times’. He said that he didn’t know a single Russian citizen and that he’d had no idea that his brother-in-law was working on the bomb, or even that there was an American project to develop a bomb, until one was dropped on Hiroshima. After the war, he and David had gone into business together, but they’d lost money, and the Greenglasses blamed him for it; he suggested that they were railroading him to get revenge, and to save their own skins. Ethel tried to back him up by testifying that her brother had often nagged them for money. When asked if they were communists, Julius and Ethel refused to answer, as was their right under the Fifth Amendment, though the jury didn’t like it. And they didn’t help themselves by not allowing anyone to testify on their behalf as character witnesses – they worried, with reason, that their friends’ reputations would suffer by association. Their overwhelmed lawyers did nothing to challenge the prosecution’s claim that David’s childish ‘descriptions of atomic energy’ and ‘sketches of the very bomb itself’ were all the Soviets had needed to build their own. After the trial, Ethel complained that her brother was a ‘simple machinist, an incompetent, and otherwise, a scientific illiterate’, hardly capable of telling the Soviets anything they wouldn’t have known from Klaus Fuchs. But by then it was too late.

The jury of twelve – one woman, no Jews – took eight hours to deliver unanimous guilty verdicts for the Rosenbergs and Morton Sobell. When interviewed, jurors said that they hadn’t liked David, but didn’t believe he would have testified against his sister if she wasn’t guilty. ‘You just do not testify against a relative unless there’s something in it,’ one said. Another had been ‘squeamish about the possibility of a woman being put to death’, but was persuaded that ‘possibly this woman that you want to save will someday be a part of a conspiracy to transmit secret information to a foreign power that would result in your own doom and the destruction of your wife and children.’ The foreman reminded the jury that the death penalty wasn’t their concern: that was up to the judge, Irving Kaufman. Years later, Roy Cohn would tell his biographer that Kaufman had secretly called the prosecutors to ask for their advice on sentencing, unsure what to do about Ethel. Cohn told him that she was older and smarter than Julius, obviously the leader of the two, and he claimed – though the prosecution had presented no evidence of this at trial – that she had been the one who had ‘engineered this whole thing, she was the mastermind of this conspiracy’. When Kaufman sentenced both Rosenbergs to death, he said he considered their crime ‘worse than murder’. To his mind, they were responsible for the Korean War, since without the bomb Stalin would have lacked the confidence to intervene. Indeed, he thought that all Cold War terror – children in New York wearing dog tags to school in case of nuclear attack, duck and cover drills – could be laid at their feet: ‘No one can say that we do not live in a constant state of tension. We have evidence of your treachery all around us every day.’ Sobell was given thirty years, and David Greenglass fifteen, which shocked him: he’d expected to walk. Ethel told Julius that she was ‘all right as long as you are’.

After sentencing, Ethel’s lawyer tried to persuade left-wing newspapers to support the Rosenbergs’ appeals, but the CPUSA wasn’t interested: for too many Americans, being a communist was already tantamount to being a traitor and the editors of the Daily Worker worried that the Rosenbergs would only taint the whole movement. At first, the only paper willing to take on the case was the radical weekly National Guardian, which argued in a series of editorials that there might never have been any atomic spies at all: the Soviets were so technologically superior to the Americans that they had probably developed the bomb first, but refused to use it for the good of humanity. The editors dismissed the prosecution’s case as a ‘hoax’ and claimed the Rosenbergs as the ‘first victims of American fascism’. Readers set up a Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case, which organised rallies and a letter-writing campaign. Not everyone was persuaded that the Rosenbergs were innocent, but they were opposed to the death penalty – either on principle, or because they didn’t like to see it applied to a young couple who appeared so ordinary and had children. Arthur Miller warned that killing the Rosenbergs would undermine ‘America’s most attractive ... point of superiority’ over the Soviet Union: ‘her humane justice’.

But the Committee to Secure Justice came under suspicion: it was widely dismissed as a front for communists; the CIA investigated its supporters for ‘commie tracking’. As Lori Clune’s Executing the Rosenbergs (2016) shows, protests over the case grew more readily abroad. The State Department planted articles in world newspapers that claimed the Rosenberg trial demonstrated ‘the superiority of the American judicial system’, but the left-wing press told a better story: the Americans had lost face and, for all their claims to moral superiority after the war, were now the ones scapegoating Jews. In Britain, Labour MPs called for the Rosenbergs’ sentences to be commuted: the executions would promote anti-American sentiment and disrupt the ‘Anglo-American accord’. On Elizabeth II’s first outing after her coronation, she saw a ‘Save the Rosenbergs’ banner draped on the Monument to the Great Fire of London. Two thousand demonstrators in Calcutta protested outside the US embassy; in Paris, tens of thousands marched on the Place de la Concorde. There was no comment from the Soviet Union. Although Eisenhower accepted that he might be playing into their hands by turning the Rosenbergs into martyrs, he feared that granting clemency would make America look ‘weak and fearful’. Besides, most Americans – according to polls at the time, more than 70 per cent – wanted them to die. In her journals, Sylvia Plath wrote that the ‘appalling thing’ was the indifference all around her. ‘The largest emotional reaction over the United States will be a rather large, democratic, infinitely bored and casual and complacent yawn.’ In The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood (Esther was Ethel’s legal name) is surrounded by girls who say they’re only too glad the Rosenbergs were going to die: ‘It’s awful such people should be alive.’

It took two years for their appeals to be exhausted. Julius had other prisoners for company – they played chess. But Ethel was the only woman on Sing Sing’s death row. At first, her occasional meetings with her lawyer were mostly spent discussing her sons’ care. Since her arrest, they had moved between her mother and various friends and relatives, and also, occasionally, an orphanage. Ethel’s mother wanted her to divorce Julius and co-operate with the government: perhaps the threat of the orphanage was a form of coercion. It didn’t work: Ethel forbade her mother from visiting. The Justice Department repeatedly told the Rosenbergs that their sentences would be commuted if they confessed and answered questions, but Julius and Ethel were adamant: they were innocent and wouldn’t say otherwise just to save themselves. Still, until the last moment, the FBI thought there was a chance they’d change their minds.

On 19 June 1953, the night the Rosenbergs were scheduled to die, two stenographers were sent to the prison in case they were needed to take confessions. Six FBI agents were there too, with a list of questions to ask Julius, including one – ‘Was your wife cognisant of your activities?’ – that shows they were rather less certain of Ethel’s guilt than the trial judge had been. According to Clune, the ‘Sing Sing warden believed that Ethel was stronger and should die first, but FBI director Hoover refused, claiming that it would look bad if Julius confessed after they had killed the mother of two children.’ So Julius died first, just before the beginning of Shabbat, then Ethel a few minutes later. ‘She called our bluff,’ the deputy attorney general said. There had been a ‘Save the Rosenbergs’ protest in Madison Square Garden that night, but it dispersed once the executions were announced. No Jewish cemetery was willing to take the bodies. In order to bury them, someone claimed that a pair of plots were needed for sisters who had died in a car accident.

Sebba argues that Ethel was the victim of a combination of Cold War hysteria and bad relatives, and that she went to her death with ‘dignity, confidence and courage’. Her Ethel is a ‘profoundly moral woman’ who ‘believed she was dying to make sure that she left her sons with not simply the memory of a mother they loved but a human role model of how to live a good life’. Of course ‘she could not confess to something which she had not done.’ But that wouldn’t have been necessary. If she had agreed to tell the government that Julius was a spy, then even after he was already dead her execution would have been called off. (In Angels in America, Tony Kushner imagines her becoming the author of ‘some personal-advice column for Ms. magazine’.) But she told her lawyer that she couldn’t do it: she was disgusted by anyone who suggested that her sentence be commuted but not Julius’s. She would ‘far rather embrace my husband in death than live on ingloriously’ at his posthumous expense:

How diabolical, how bestial, how utterly depraved! Only fiends and perverts could taunt a fastidious woman with so despicable, so degrading a proposition! A cold fury possesses me and I could retch with horror and revulsion, for these unctuous saviours, these odious swine, are actually proposing to erect a terrifying sepulchre in which I shall live without living and die without dying!

While in Sing Sing, she read Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan and wrote out Joan of Arc’s speeches. As the months went on, she spent less time talking to her lawyer about her sons: she wanted his editorial help instead, to make her letters – bound for publication – more literary. She was delighted that in Holland a child had been named Ethel Julia in her honour, and told the readers of the National Guardian: ‘I pledge myself anew to the unceasing war against man’s inhumanity to man in whatever form it may rear its brutal head. I shall never sell short the faith and trust that the Guardian readers have reposed in my husband and me.’ In the end, she had fallen in love with her own martyrdom.

Book author Anne Sebba is a prize-winning biographer, lecturer, and former Reuters foreign correspondent who has written several books, including That Woman and Les Parisiennes. A former chair of Britain’s Society of Authors and now on the Council, Anne is also a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research. She lives in London. Her website is at https://annesebba.com/

[Essayist Deborah Friedell is a contributing editor at the London Review of Books. A miscellany of her essays is available HERE . Friedell’s podcast on the Rosenbergs can be accessed HERE.]

Spread the word