“WE ALL QUIT, SORRY FOR THE INCONVENIENCE,” disgruntled employees posted in giant letters on a sign outside a Burger King in Lincoln, Nebraska earlier this month.

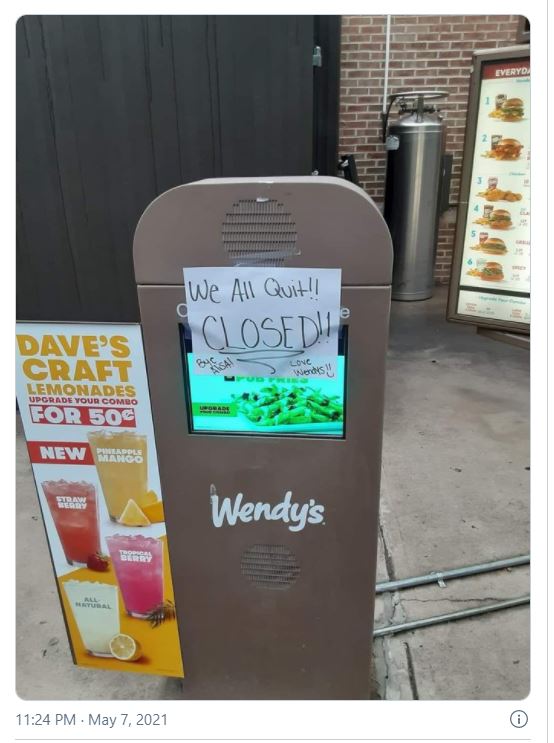

"Almost the entire crew and managers have walked out until further notice," Chipotle workers wrote in Philadelphia on a sign posted on the glass doors of their restaurant.

“Closed indefinitely because Dollar General doesn’t pay a living wage or treat their employees with respect," retail workers scribbled in Sharpie outside a Dollar General in Eliot, Maine, after the entire store quit en masse.

In recent months, these mass resignations have been part of a national reckoning over a so-called "labor shortage." On one hand there are the businesses that want to continue to pay workers what they've always made (which is very little). On the other, workers and those who support them say there needs to be a fundamental reassessment of what work looks like in the United States.

Why are low-wage workers quitting their jobs now?

For the first time in more than two decades, fast food, retail, and hospitality workers have the leverage to resign from their jobs in protest of decades of deteriorating working conditions, which often include stagnant wages, unpredictable schedules, and no health care or paid sick leave.

A better social safety net during the pandemic and a tight labor market in the fast food, leisure, and hospitality industries is allowing this to happen. Historically, these sectors are among the least protected by labor laws and the most precarious workers in the country; many of them were deemed "essential" during the worst parts of the pandemic.

"It's an act of protest against abuses and exploitative conditions," said Patricia Campos Medina, executive director of the Worker's Institute at Cornell University. "It’s a sense of empowerment that workers don’t have to tolerate that kind of abuse."

For decades, large swaths of low wage service work have proved difficult to unionize because of fissured workplaces and aggressive union-busting by employers. Now these workers, many of them women of color—have taken the next best option, protesting through mass resignation.

Many conservative pundits have blamed unemployment and stimulus checks for the labor shortage. In 2020, a relief bill added $600 per week to state unemployment benefits. This year, that has fallen to $300 per week, and is set to expire on September 4. But recent academic studies show that extra stimulus money and unemployment insurance doesn't seem to have kept low-wage workers from reentering the job market more than usual. Many workers have just found other jobs, retired early, and even died.

Employment benefits have given workers a little more time to find jobs and higher expectations in their job search. "Workers have seen during the pandemic that when lawmakers choose to step in and act and protect people [via stimulus checks, unemployment benefits, healthcare], work doesn't have to suck as much. When workers are asked to do tough jobs, they want to be paid more," David Cooper, senior policy analyst at the Economic Policy Institute said. "For the first time since the late 1990s, low wages workers have the leverage to demand higher pay. The workers who walk out of Burger King are using this to their advantage."

Historians say this is one of the few moments in modern US history when precarious, low-wage workers have really had this leverage. "The other really obvious example of this was World War II when you had even more government payments to people," said Nelson Lichtenstein, a history professor at UC Santa Barbara. "It was money to [use to] go out and find jobs that pay better wages." Then—as today—those fleeing their jobs in the greatest numbers were people of color and women.

"Real wages for Black people in Mississippi went up four times," Lichtenstein continued. "Some left for jobs in the ports of California. Women also left lousy jobs and white collar work opened up which was better. Domestic workers fled their jobs as maids and cleaners and got steady jobs in hospitals. When you give people an alternative, they seize the opportunity."

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 grants workers in the United States the right to form unions and bargaining with their employers for better wages and working conditions, but fast food and retail workers have long faced enormous barriers to forming unions thanks to franchised, contracted, and high turnover jobs. For example, there have been concerted efforts to unionize McDonald's and Walmart, but these have failed. McDonald's, for example, maintains that the vast majority of its workers are not employees of McDonald's but work instead for franchises, and unionization would have to go franchise by franchise, or McDonald's would have to agree to sit down at the bargaining table.

"The workers who are walking out today are at the margins of formal labor law and standards," Jennifer Klein, a professor of labor history at Yale University said. "They don't have access to bureaucratic mechanisms of the state and law to resolve grievances and they don't have collective power through a union. Low wage workers have so often been rendered invisible but now they're making themselves incredibly visible through informal means."

Where are workers going and are they actually getting paid more?

While some professionals are quitting because of burnout or existential crises, according to a New York Times article about the phenomenon from April, low wage workers don't have the savings or other financial cushion to leave the job market for extended periods of time to explore passion projects and travel, Cooper says.

But people are finding better jobs in the same industries, or entirely new ones. Cooper says the expanded social safety net has left workers wanting and expecting more, and has allowed them to spend a little more time out of the workforce looking for the right job. "In general, unemployment benefits give workers the ability to wait for better jobs and better working conditions," said Cooper. "They're taking time to pick the right jobs. Those jobs might be closer to their interests, closer to what they studied, jobs that are a career rather than a means to pay the bills."

Still, while employers in certain regions may in fact be offering higher wages than they usually do, there's no data yet showing that employers across the board are paying workers more.

Instead, many companies have resorted to offering hefty sign-on bonuses and other perks, such as free meals or cash for interviewing. In recent weeks, Amazon—where workers too are quitting—has offered enormous sign-on bonuses to warehouse workers across the country. For example, an Amazon warehouse in the Hudson Valley, New York recently offered a $3,000 sign-on bonus if workers start before August 1 and work certain shifts.

"Employers are smart too," said Lichtenstein, the history professor at UC Santa Barbara. "What they don’t want to do is establish a permanent higher norm, so instead of $15 an hour, they say here’s a bonus. You can have free lunches. We'll pay for your tuition. Employers will do anything to not improve wages in a permanent fashion."

The myth of at-will employment

Conservative pundits love to belabor the point that in America, employment is at-will, and workers and employers alike have the right to call it quits at any moment. "If you hate your job so much, why not leave? This is a free country after all," they say.

In reality, for decades saying "take this job and shove it" to McDonald's or Burger King has become increasingly hard thanks to the stagnant wages, a lack of benefits, non-compete clauses, and long stretches of economic recession that make it very difficult for workers to build up the kind of savings or emergency fund needed to quit without going through serious financial distress.

For the last 40 years, low wage workers across the United States have seen their pay, benefits, guaranteed hours, and schedules get progressively worse. Unemployment benefits have been harder to access. Companies such as Jimmy John's, McDonald's, Carl's Jr., and Amazon have required workers to sign non-compete clauses and no-poach agreements that extend for months that legally bar workers from going to competitors in search of higher wages. Low-wage workers don't have the luxury to quit and wait six months to start working again, as a recent executive order from the Biden Administration is attempting to address by banning and limiting such clauses.

"Flexibility to look for better jobs has been eroded intentionally through policy choices and campaigns to undermine workers' leverage and ability to expect more from employers," said Cooper.

Raising expectations?

When Ieshia Townsend signed up to work at a McDonald's on the South Side of Chicago in 2015, it wasn't because she loved the idea of flipping burgers and working the take out window. She had just had a baby, and was caring for her mother who had Alzheimer's disease and a brother with epilepsy. It seemed like the best job she could get. "I couldn't pay rent," she said. "I couldn't pay lights or gas or cable, so I went into McDonald's and I said, 'God please make a way to provide for my mom, son, and brother.'"

Fast forward six years to this spring, after a year of working in a pandemic, Townsend quit her job after a bout of panic attacks that landed her in the emergency room and a recommendation from her doctor that she quit McDonald's to take care of her health. "It was the anxiety and the heat. I worked all the way through the pandemic. It was very stressful knowing I can’t touch my kids when I get home," she said.

Part of the mass resignations can be attributed to the fact that the pandemic has raised expectations for safety and benefits in the workplace. Jobs that don't offer health insurance and paid sick days have never been desirable, but now some workers are saying they're done putting up with them.

"I think the most fundamental fact is that the fast food and restaurant industries are having a structural shift in how people see the jobs and what workers and consumers expect of the industry," said Campos Medina at Cornell University. "Fast food has always been portrayed as the job of teenagers, not women sustaining families, but that is what it is. The pandemic revealed that people in these jobs have no job security, or health insurance, and couldn’t qualify for Medicaid."

Townsend, the McDonald's worker in Chicago who resigned, said she's found now work in the gig economy—which also has its drawbacks—and is testing out different food delivery apps, UberEats, DoorDash, and Instacart, to see which she prefers.

"It got to the point where I was having chest pains, my chest was throbbing and my manager would say 'you're fine' and wouldn't let me leave, so I just quit," she continued. "I would never work at McDonalds ever again."

[Lauren Kaori Gurley a senior staff writer for Motherboard. Writer her at lauren.gurley@vice.com]

Spread the word