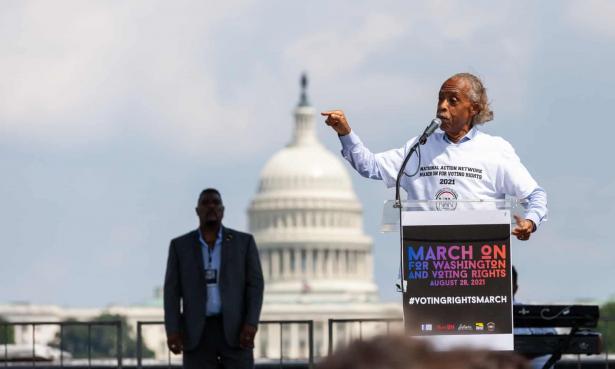

Defying the punishing August heat, the Rev Al Sharpton recently led a gathering thousands strong through the streets of the nation’s capital on the 58th anniversary of the March on Washington, when Martin Luther King Jr delivered his immortal I Have a Dream speech on that day in 1963.

Now, as then, there was an urgency to their march. In statehouses across the country, Republicans are proposing – and passing – new voter restrictions that activists say amount to the greatest erosion of voting rights since the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, a crowning achievement of the civil rights movement.

Speaking near the White House, Sharpton recalled Joe Biden’s victory-night promise to lead the “great battle” for racial justice. The time to fight had come, the reverend told Biden.

“You said the night you won that Black America had your back, and that you were going to have Black Americans’ backs,” Sharpton said. “Well, Mr President, they’re stabbing us in the back.”

Since taking office, Biden has placed racial justice at the center of his governing agenda, embedding language that promotes equity into his executive orders, policy proposals and public speeches. “The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer,” he vowed in his inauguration address. “We can deliver racial justice.”

Yet the escalating fight over voting rights underscores the difficulty Biden faces in his efforts to advance racial equity. It is an issue that is critical to his legacy but one that faces a myriad of political and legal obstacles. From voting rights to policing reform to helping Black farmers and other critical issues, Biden’s racial justice agenda has suffered a wide array of setbacks and delays during his first year in office.

Despite controlling the White House and Congress, Democrats have yet to pass a pair of federal elections bills that are the centerpiece of the party’s strategy for beating back the sweep of new voting restrictions in Republican-led states.

The bills include the For the People Act, a far-reaching overhaul of federal election laws that would expand early voting, automatic and same-day registration, and prevent the severe manipulation of district boundaries for partisan gain; and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would restore critical pieces of the 1965 Voting Rights Act after supreme court rulings gutted the law.

“To address 400 years of racial oppression in this country, you must first protect the rights of all citizens, and particularly African Americans, to fully participate in our democracy,” said Derrick Johnson, the president of the NAACP.

“All public policy germinates from that overarching right to vote,” he added. “If you suppress the right to vote, you cannot advance public policy to address the systemic barriers.”

In a speech commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa race massacre, Biden called voting rights “fundamental” to ensuring racial equity and charged his vice-president, Kamala Harris, with leading the effort to pass legislation on Capitol Hill. In a second speech earlier this summer, he decried Republican efforts to restrict voting as the “most significant test of our democracy since the civil war” and implored lawmakers to act.

But the bills remain stalled in the evenly divided Senate, where the filibuster requires 60 votes to advance legislation. The lack of progress has frustrated civil rights leaders and activists who charge that the president isn’t taking the fight for voting rights seriously enough.

“What we have seen to date in terms of action does not match the passion of the president or the vice-president’s rhetoric,” said Nsé Ufot, the executive director of the New Georgia Project. “It doesn’t match the intensity of their speeches and it certainly doesn’t match the urgency of this moment.”

Ufot is among a coalition of civil rights advocates pressuring Biden to invest the same political capital and urgency into voting rights as he has other issues like infrastructure and the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.

They say the president and Democrats are wasting precious time trying to persuade Republicans to support the bills. Instead, they are calling on the party to eliminate the filibuster altogether or to carve out an exception to the filibuster allowing voting rights legislation to pass on a party-line vote without Republican support.

“The question is, when are we going to talk about the filibuster and getting rid of it?” Ufot said. “Because that appears to be the only path forward to getting this passed.”

Biden and the White House have countered the criticism, citing the lack of support among Senate Democrats to further chip away at the filibuster. At least two senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, are reluctant to restrict the use of the filibuster – the very tool Republicans used to block consideration of the For the People Act earlier this summer.

Democrats’ narrow majorities have made progress on other aspects of his racial agenda equally difficult.

Biden’s deadline for passing a federal police reform bill by the first anniversary of the murder of George Floyd went unmet as lawmakers repeatedly failed to reach a consensus. Negotiations are ongoing but its prospects remain dim.

Measures included in his infrastructure proposal to address historic inequities were cut as part of a bipartisan deal backed by the president – among them, a $20bn initiative to rectify the damage caused decades ago by highway construction in Black and Latino communities was reduced to just $1bn. The plan also scrapped a $400bn proposal to improve long-term care for older and disabled Americans. The program would have helped lift wages for care workers, who are predominantly women of color.

Conservative lawyers are also closely monitoring the Biden administration’s actions. Legal challenges have stymied some of the administration’s attempts to promote racial equity.

This summer, a federal judge halted a federal program that would forgive the debts of Black farmers after generations of race-based discrimination. The hold was in response to lawsuits filed by white farmers who said the program was unfair and discriminatory. In another legal challenge, white business owners successfully challenged an administration policy to prioritize applicants for pandemic relief grants from women and people of color. As a result, grant approvals for nearly 3,000 priority applicants were rescinded.

Last month, the supreme court rejected the Biden administration’s latest attempt to extend a federal moratorium on evictions, which have disproportionately affected Black and Latino families during the pandemic.

Yet the obstacles have not stopped the administration from making progress on other fronts.

Many civil rights leaders were encouraged by Biden’s opening act as president. He appointed one of the most diverse cabinets in history, which includes the first Black and Asian American female vice-president; and he signed a flurry of executive orders that aim to make racial equality “the responsibility of the whole of our government”. Among them were actions to address housing discrimination, phase out the Department of Justice’s use of private prisons, rescind a Trump-era commission that sought to minimize the role of slavery in the nation’s founding, ensure that vaccines were distributed equitably and expand voting rights. In June, Biden signed into law a bill that established Juneteenth as a federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

And the $1.9tn coronavirus relief plan that Biden pushed through in March released billions of dollars in aid to poor families, spurring a dramatic reduction in poverty, especially for Black and Latino families.

And in July, the justice department, under the leadership of the attorney general, Merrick Garland, announced that it was suing Georgia over a sweeping voting law on the grounds that the measure discriminated against Black voters.

Voting rights, advocates say, pose the most significant test of whether Biden can deliver on his promise to combat systemic racism in America. The consequences of failure are hardly hypothetical, they say.

At least 18 states enacted 30 laws making it harder for Americans to vote as of mid-July, according to an analysis by the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice. On Tuesday, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas signed into law a sweeping new measure overhauling the state’s elections that critics say will make it one of the hardest places in America to vote, particularly for people of color.

“Central to the work of racial justice is ensuring that Black and brown, our most marginalized communities, our most marginalized residents of this country, have access to the ballot,” said Taifa Smith Butler, president of Demos, a Washington thinktank that promotes racial equity. “We need bold, courageous leadership from the administration in the protection of this democracy, because the fears that we have today can only be quelled by the passage of these two voting rights bills.”

Lauren Gambino is political correspondent for Guardian US, based in Washington DC. Twitter @laurenegambino

Spread the word