Contrary to popular belief, the evolution of wine precedes agriculture and the domestication of grapes. The genesis of wine may even predate our species. Over the millennia, humans have radically transformed viticulture from a happy accident to a scientifically precise art form and global industry. At the same time, the juice of fermented fruits shaped us—our religions and rituals, our economies, and even our genes.

This most human and ancient of beverages is ripe for anthropological investigation. Archaeologists have excavated an Armenian cave that’s home to the world’s oldest-known winery, analyzed residue from 9,000-year-old Chinese pots in search of the chemical signature of grapes, and dove into the ocean to examine Greek wine amphorae in a shipwreck. Meanwhile, sociocultural anthropologists have explored wine and cultural identity in France, wine and the politics of place and labor, and wine as a perfect synthesis of nature, culture, and technology.

Let’s decant the story they’ve uncovered, in five major developments.

1. Drunken Monkeys: The Roots of Wine Drinking

The dawn of wine, like the origin of art, is continually being pushed back in time by new research. According to the drunken monkey hypothesis, conceived by integrative biologist Robert Dudley in the early 2000s, early hominids and other primate species have had a taste for boozy fruit for millions of years. Dudley has suggested three reasons for this predilection:

- Fermenting fruit was easier to smell and locate—and hence, consume.

- It offered healthy probiotics and antimicrobial properties, plus a caloric boost: Ethanol (the alcohol produced when yeast ferments sugars) has nearly twice the calories of carbohydrates.

- The mild buzz of ethanol eased the tension of life in the jungle. Alcohol levels were low, and consumption was moderate, since properly drunken monkeys would have made easy prey.

At least 10 million years ago, a critical gene mutation in primates created the ADH4 enzyme, which made it possible to digest ethanol up to 40 times faster than previous species did. The enzyme allowed our ape ancestors to enjoy even more overripe, fermenting fruit without suffering ill effects.

Since grapes didn’t grow in sub-Saharan Africa, our Homo ancestors probably made the world’s first wines by fermenting high-sugar fruits like figs or marula, a tart, juicy tree fruit. Wine can in fact be made from a variety of fruits, though today almost all wine is crafted from grapes—specifically from one highly versatile grape, Vitis vinifera sylvestris.

Before ancient humans encountered wild Eurasian grapes, they may have fermented fruits such as marula (shown here). Jouan/Rius/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

2. Grape Expectations: Stone Age Wine

The wine we know and love arose sometime after Homo sapiens ventured out of East Africa about 2 million years ago and first tasted Vitis vinifera sylvestris, wild Eurasian grapes. These early encounters may have taken place in present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, or perhaps farther north in Turkey, Syria, or Iran.

Whether they discovered grape wine by accident or deliberately put a twist on traditional African techniques remains unknown. Anthropologists, however, largely support the Paleolithic hypothesis, developed by anthropologist Patrick McGovern, to explain how the world’s first grape wine was made. Here’s how it (probably) went down:

While gathering food, roaming bands of humans chanced upon wild grapes, which they placed in woven baskets or gourds (since we’re talking about life before ceramics) and brought them back to camp. The weight of the fruit on top crushed some grapes, and juice pooled at the bottom of the vessel. In the warm climate, it would take only a few days for the yeast on the grape skins to begin fermenting the liquid.

After eating all the grapes, our ancestors must have been enchanted by the aromatic, mildly intoxicating juice. Liking what they tasted and felt, they would have made intentional grape pressing standard practice. Voilà, wine was born! It needed to be consumed quickly, however, since preservation methods were still a long way off.

As logical as it sounds, the Paleolithic hypothesis is just that—an educated guess. So far, it’s impossible to prove, since there isn’t any primordial wine to exhume from the earth. The organic baskets and containers are also long gone. Researchers do have solid evidence, however, for identifying the transition from wild to domesticated grapes, which coincides with the widespread shift from Stone Age foraging to Neolithic farming.

3. Drinking History: From Wild to Domesticated Vines

Evidence suggests the domestication of grapes took place during the Neolithic period, from around 8,500 to 4,000 B.C., in the Transcaucasian region between the Black and Caspian seas. Wild grapes still thrive in parts of this ecologically diverse area, which comprises modern-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

Researchers use numerous methods to pinpoint when and where grapevines were first deliberately cultivated, incorporating insights from archaeology, genetics, linguistics, and literary studies. But one of the hardest forms of evidence comes from ancient seeds. Advances in paleoethnobotany (the archaeological study of people-plant relations) demonstrate morphological differences between wild and domesticated grape seeds from around 6000 B.C. onward.

Inside the Areni-1 cave complex in Armenia, archaeologists found evidence of the world’s oldest-known winery, including a wine press and fermentation vessels more than 6,000 years old. Gerd Eichmann/Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, biomolecular archaeologists have identified grape wine residue and tree resin—which is used as a preservative—in Neolithic pottery vessels shortly after the seeds began to change. These findings are further validated by climatic and environmental reconstructions, along with archaeobotanical evidence of grape pollen across Western Asia.

Socioculturally, a host of conditions had to be in place for the wild grapevine to become cultivated. Permanent human settlement was the most significant because vines require year-round tending, including watering and protecting them from animals, pests, and other people. Plus, in order for wine to be enjoyed all year—as opposed to being a seasonal indulgence, as it was for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers—airtight ceramic vessels had to be invented to prevent the drink from spoiling or turning into vinegar.

So, wine culture primarily matured in the early agricultural communities of Western Asia, followed by the Mediterranean and North Africa, taking its central place in numerous religions.

4. Divine Wine: From Mythic Tales to Modern Tastes

Across the ancient winemaking cultures of Western Asia and the Mediterranean, wine belonged to the realm of the sacred. In Genesis, the Biblical account of origins, Noah’s first task after landing his ark on Mount Ararat was to plant a vineyard. Yet Noah’s tale is a variation on the earlier Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, who may be the first mythic vigneron.

The Greeks came to worship Dionysus, the god of the vine, who also arrived from Mesopotamia and later become Bacchus in Roman mythology. Naturally, wine was served at the Biblical story of the Last Supper, and the ancient elixir came to symbolize the blood of Christ in the Christian ritual of communion.

Ancient Egyptian religion also made a strong symbolic association between blood and wine, in part because both are red. As McGovern observes, crushing grapes was linked metaphorically with bloodshed but in a way that symbolized restoring balance and order to the world. The god of the red-stained winepress, Shesmu, was known as the “slaughterer,” whose wrath was especially directed at enemies of the pharaoh.

Before the biochemistry of fermentation was scientifically understood, the magical transformation of grape juice into wine was seen as the work of divinities. With its ability to lift the spirits and encourage conviviality, friendship, and even love, wine was considered a gift of the gods. Along with its place in religious rituals and celebrations, wine’s medicinal use for all kinds of ailments and the fact that it was generally safer than water further conferred its sacred status.

While the mythico-religious view of wine continued for millennia and still persists for some followers of Christianity (and perhaps ardent oenophiles), certain breakthroughs made during the scientific revolution and Enlightenment marked a new phase in wine history.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, wine quality vastly improved through dramatically fuller comprehension of chemistry. For thousands of years, sour and spoiled wines were the norm, according to the records of Pliny the Elder and other historians who described techniques such as adding resin, gypsum, ashes, herbs, and seawater to prevent rot and mask “off” flavors. The spoilage was mainly due to excessive amounts of oxygen and bacteria getting into vessels, which, despite winemakers’ best efforts, lacked proper seals and sanitation.

Using updated tools and techniques, modern vintners make cleaner, stabler, and ultimately superior wines compared to ancient times. As wine began to taste better and improve with age, and distinct styles emerged (many still recognizable), it became the aesthetic object and status symbol it is today.

5. New Worlds and the Globalization of Wine

From early trade routes across Western Asia, the Mediterranean, and North Africa, wine flowed throughout Europe and eventually to the colonized territories of the Americas, Southern Africa, and New Zealand and Australia. In countries such as Chile, Argentina, South Africa, the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, “New World” wine was born.

“Old World” wine generally points to Western and Southern Europe and carries connotations of traditional winemaking methods and a deep emphasis on the sense of place expressed in wine, known in French as terroir. Less bound by history and tradition, New World wine is typically viewed as more experimental and innovative, and often has bolder and more fruit-forward flavors.

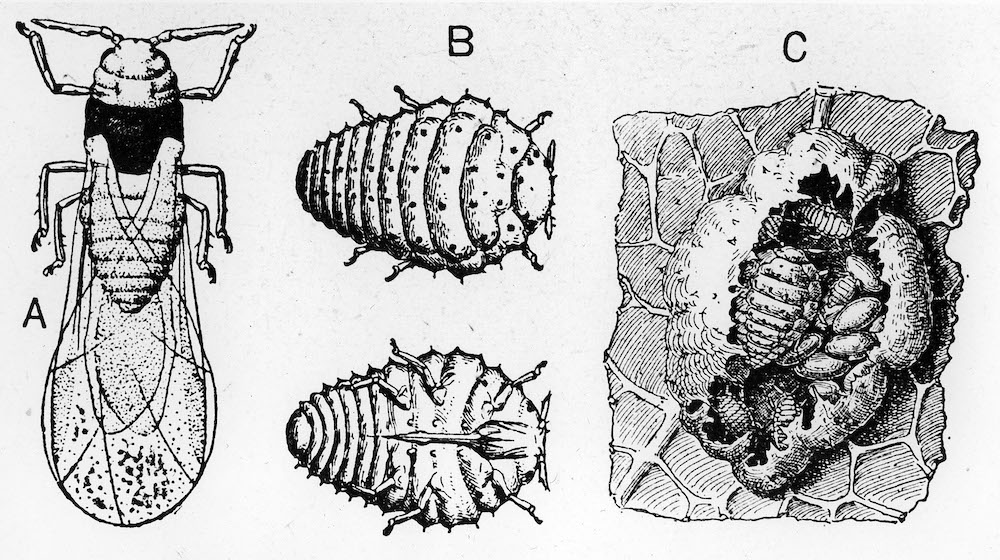

New World wine became increasingly important following the phylloxera plague of the mid-to-late-19th century. This tiny insect decimated the vineyards of Europe, especially in France, leaving a global shortage of wine that the relatively unscathed New World was only too happy to supply. Winemakers found that the solution to the plague was to graft European V. vinifera onto the roots of American vines. Most wine is still produced from these grafts or hybrids.

In the 1800s, a phylloxera infestation wiped out vineyards in much of Europe, forever changing the winemaking world. Photo12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Nevertheless, New World wine was long considered (and still is by some connoisseurs) inferior to wines of the Old World, with its 8,000-plus years of history and tradition. A turning point, however, was the so-called Judgment of Paris in 1976. This event pitted the recognized top wines of France and California against one another in a blind tasting by France’s preeminent wine critics. Lo and behold, California came out on top, and many experts in the Old World conceded that fine wine could be made elsewhere.

Into the new millennium, the globalization of wine has reached ever-increasing heights, making inroads in massive new markets in East and South Asia. China, for example, now has numerous wine-producing regions. More and more Indigenous peoples are becoming involved in winemaking in places such as New Zealand, North America, and Chile. And due to climate change, vines are being planted in places that were previously too cold to ripen grapes, such as in Scandinavia and Patagonia.

When we pour, swirl, and taste wine, we’re joining a long ritual procession of our human and pre-human ancestors. So, let’s not only raise our glasses to Old Europe, but also to our forebears in Western Asia and Africa, and the people around the world who are adding new dimensions to the remarkable evolution of wine.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.

Christopher Howard -- I’m an anthropologist interested in the changing relations between humans, technology and the environment. As such, I explore a wide range of topics from an interdisciplinary perspective, mostly through the lens of social theory, philosophical anthropology and phenomenology. I also have a special interest in wine and viticulture, having worked previously in the California wine industry. Currently, I teach anthropology for Chaminade University of Honolulu, Massey University (NZ) and conduct research for the New Zealand Ministry of Economics. I also consult as an organizational anthropologist and write about wine for several publications. Originally from Sonoma, California, I reside in Wellington, NZ.

SAPIENS is a digital magazine about the human world. It’s about how we communicate with each other, why we behave kindly and badly, where and when we evolved in the past, and how we live and continue to evolve today. It’s about the relationship between our laws and ethics, the cities we build, and the environment we depend on. It’s about why sex, sports, and violence consume and intrigue us, what life was like in centuries past, where we might be headed in centuries to come, and much more.

In January 2016, we launched SAPIENS with a mission to bring anthropology—the study of being human—to the public, to make a difference in how people see themselves and the people around them. Our objective is to deepen your understanding of the human experience by exploring exciting, novel, thought-provoking, and unconventional ideas.

Through news coverage, features, commentaries, reviews, photo essays, and much more, we work closely with anthropologists and journalists to craft intriguing and innovative ways of sharing the discipline with a worldwide audience. To expand our reach, we syndicate articles at The Atlantic, DiscoverMagazine.com, ScientificAmerican.com, and other publications. We are fully funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and published in partnership with the University of Chicago Press, while maintaining unconditional editorial independence.

SAPIENS aims to transform how the public understands anthropology. Every piece of content is grounded in anthropological research, theories, or thinking. We present stories and perspectives that are authoritative, accessible, and relevant—but still lively and entertaining.

We hope you will return often to SAPIENS, where we strive to regularly deliver fresh, delightful insights into everything human.

Spread the word