A century and a half ago, Russia lost a war it might have expected to win. The consequences reached far and wide

Can history offer any clues? Vladimir Putin likes to talk about the second world war, Russia’s best war, but the closest parallel is probably the Crimean war, which dragged on for two and a half years, from 1853 to 1856, before the exhausted belligerents worked out a peace agreement.

An underachieving Russian military failed to achieve any of its goals. But the British and French, who forged an alliance with the Turks, encountered frustrations of their own as they groped toward a victory that felt pyrrhic at times. Surprisingly, one of the war’s great legacies was felt in the US, where an unexpected chain of events, tied to Russia’s defeat, helped to end slavery.

Can any lessons be drawn from the Crimean war today?

Wars end differently than they begin

Carl von Clausewitz wrote: “In war more than anywhere else things do not turn out as we expect.” Few expected war in 1853. When it came, most predictions turned out to be inaccurate, including a belief that the Russian army was invincible, especially when fighting close to the Motherland.

The Crimean war began for the smallest of reasons, when Russian and French monks quarreled over who held the right to a key to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. As it turned out, that key would unlock Pandora’s box, leading Russia’s tsar, Nicholas I, to invade the Ottoman empire with hopes of gaining Constantinople, now Istanbul.

The Ottomans were joined by France and Britain, which sent ships and troops to the Black Sea. A war of attrition ensued, including naval battles as far away as the Baltic and the Pacific.

Poorly trained soldiers fight poorly

Before the Crimean war, Russia’s huge army was feared throughout Europe. But its weakness soon became evident. With demoralized troops, many young conscripts or landless serfs, Russia lost most engagements and ended the conflict with its military reputation in tatters. Its weapons were vastly inferior to those of the British and French, who had steam-powered frigates and rifles that fired accurately over long distances.

Despite these advantages, victory came at a high price and there were strains within the alliance. Serious tactical blunders stopped the French and British winning more decisively and each side suffered about 250,000 casualties, most of whom died from disease. That led to a third lesson …

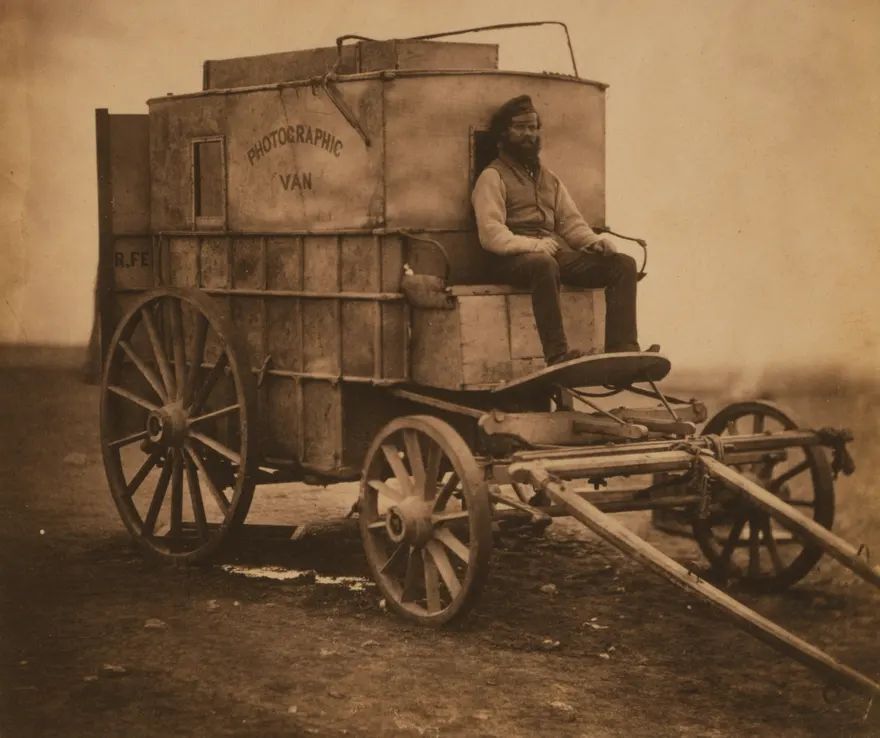

Roger Fenton’s mobile dark room. Photograph: Roger Fenton/Library of Congress

It is difficult to wage an unpopular war

The invention of the camera and the telegraph allowed a new breed of witness to cover the Crimean war in detail. There were still treacly accounts of derring-do – an insipid memento of the conflict was Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem, The Charge of the Light Brigade, which turned a colossal act of stupidity – the rash order of a general to attack an impregnable position – into a puddle of Victorian piety.

But the spread of photography and rapid dispatches from the front muted this old-fashioned kind of writing, much as cellphones have blunted Putin’s efforts to brand his invasion a success, and focused attention on possible war crimes. Working out of a wine wagon converted into a mobile dark room, a British photographer, Roger Fenton, was able to capture the visual story of the war with images of stunning clarity. Journalists filed stories from the front, so readers in London and Paris could experience the war from their armchairs. That helped build support when the war was going well but it also raised the pressure when it was not.

Even American readers were following the war, thanks to the remarkable reporting of a London-based German reporter, Karl Marx, who filed 113 articles for the New York Tribune. Marx was a harsh critic of Russia’s military adventure, pointing out its strategic vagueness, its ineptitude and its utter waste of human life. Denouncing the tsar as an “imperial blunderer”, he poured out vitriol that might make Putin wince today: “Only a miracle can extricate him from the difficulties now heaped on him and Russia by his pride, shallowness, and imbecility.”

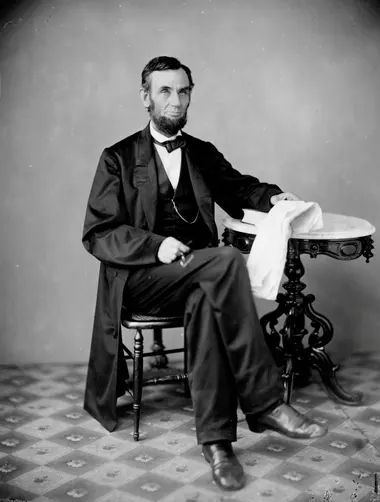

Abraham Lincoln, in an image taken in 1863. Photograph: Alexander Gardner/Reuters

A vague peace will lead to new problems

The Treaty of Paris ended hostilities in 1856 but left unaddressed many other concerns, including the porousness of south-eastern Europe’s boundaries – the “Eastern Question” would plague leaders until the first world war in 1914. After a relatively long peace following the Napoleonic era, the Crimean war unleashed a new volatility in great power politics. Europe would see a series of small, nasty wars before the immense carnage of the 20th century.

Wars have distant consequences

Nicholas I died in 1855. His son, Alexander II, accepted defeat but then did a remarkable thing. Looking at the causes of the disaster, he recognized that Russia’s performance was related to its rigid class structure and heavy reliance on serfs. Accordingly, he abolished serfdom with a proclamation of emancipation on 3 March 1861.

By coincidence, that was the day before Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president of the United States. Lincoln understood the power of the precedent and issued an Emancipation Proclamation of his own, on the first day of 1863.

In other words, a war that had nothing at all to do with freedom when it started helped make possible one of the greatest manumissions in history, on a different continent, a decade later.

The American purchase of Alaska was another legacy. After Crimea, the young tsar knew he could not defend this distant frontier and decided to sell it to a nation with a more realistic hope of populating it someday.

In that, and in so many other ways, we continue to live in a world shaped by a small, mostly forgotten war in south-eastern Europe.

Ted Widmer is a distinguished lecturer at the Macaulay Honors College of the City University of New York and the author of Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington, published in the US by Simon and Schuster

Your support helps protect The Guardian’s independence and it means we can keep delivering quality journalism that’s open for everyone around the world. Every contribution, however big or small, is so valuable for our future. Click HERE to donate to The Guardian.

Spread the word