The Justice Department’s filing Tuesday evening in former President Trump’s federal court effort to slow the Mar-a-Lago investigation presents a remarkable show of strength and confidence in the ongoing probe.

The document’s legal arguments are not particularly engaging, as they respond to uninteresting, meritless legal challenges from the former president. Its factual summary, by contrast, is a rip-roaringly great read, one in which the department tells the story of its investigation in some detail. Some of this story it has told before, but some it has not. There are a lot of new details in here, and nearly all of them are bad for the former president.

Some of these flesh out the volume and nature of the classified material Trump hoarded at Mar-a-Lago. But other details, more importantly in our view, flesh out questions of intent and mens rea that are key to all of the statutes at issue in the warrant. While the document goes out of its way not to discuss Trump’s personal behavior, it also includes material specifically suggestive of the degree to which the department has collected material incriminating Trump personally.

All of which suggests some preliminary answers to key questions: How big a problem is the Mar-a-Lago investigation for Trump? How long is this going to take? Specifically, as we shall explain, it suggests that the investigation is a very big problem for Trump, one in which he appears to have a great deal of exposure. But it also suggests that the investigation is going to take a while—a point on which a careful reading of the filing leaves little doubt.

The release of this damaging material by the Justice Department is almost entirely a result of Trump’s own actions—or at least those of his legal team. At each stage of this investigation, including the search itself, the Justice Department has been careful to resist releasing additional information about the probe—only for Trump to open the door for the department to weigh in by complaining about the investigation. This one is no exception.

Trump’s original motion seeking the appointment of a special master was not subtle in framing the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago as an abuse of power on the part of the Biden administration: It opened with the solemn invocation that “olitics cannot be allowed to impact the administration of justice,” portrayed Trump as “ask the Government the questions any American citizen would ask under the circumstances” accused the FBI of pursuing “a raid my home with a platoon of federal agents when I have voluntarily cooperated with your every request” and condemned the government for “declin to provide even the most basic information about what was taken, or why.” Arguably, the Justice Department’s detailed account of its investigation only seeks to answer these questions—but it does so with a level of detail that is incredibly damning for Trump.

The new filing contains a great deal of evidence of classified material held improperly at Mar-a-Lago. The Justice Department quotes a letter sent from the department to Trump’s counsel on April 29 stating that, according to the National Archives, the documents at Trump’s estate included “over 100 documents with classification markings, comprising more than 700 pages,” among them material with “the highest levels of classification, including Special Access Program (SAP) materials.” In May, after the FBI’s first visit to Mar-a-Lago, the bureau received “184 unique documents bearing classification markings, including 67 documents marked as CONFIDENTIAL, 92 documents marked as SECRET, and 25 documents marked as TOP SECRET.”

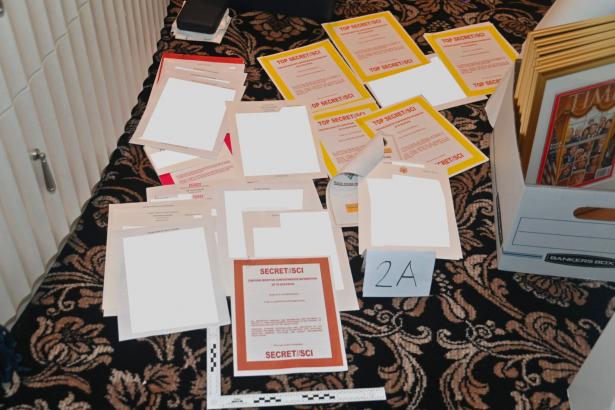

The material seized during the August search included some documents so sensitive that “even the FBI counterintelligence personnel and DOJ attorneys conducting the review required additional clearances before they were permitted to review” them. The filing states that “he classification levels ranged from CONFIDENTIAL to TOP SECRET information, and certain documents included additional sensitive compartments that signify very limited distribution.” For visual learners, the Justice Department has also included a striking photograph of documents labeled SECRET/SCI and TOP SECRET/SCI, including some with markings indicating information obtained from human sources.

Yet the story the department tells in the filing is not just about the highly sensitive nature of the documents. The document spends a great deal of time on the question of intent, which is key to all three statutes listed in the original search warrant. The first of these, 18 U.S.C. § 1519, states that “hoever knowingly alters, destroys, mutilates, conceals, covers up, falsifies, or makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States” commits a crime (emphasis added).

The second, 18 U.S.C. § 2071, states that “hoever willfully and unlawfully conceals, removes, mutilates, obliterates, or destroys, or attempts to do so, or, with intent to do so takes and carries away any record, proceeding, map, book, paper, document, or other thing, filed or deposited with any clerk or officer of any court of the United States, or in any public office” commits a crime (emphasis added).

The third statute, 18 U.S.C. § 793, prohibits “willfully retain” information “relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation” and “fails to deliver it on demand to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it” (emphasis added).

In other words, all three statutes require something more than accidental mishandling of material.

Throughout the filing, the department takes pains to set out evidence that could speak to the intent of Trump and the people around him—beginning with its description of the referral from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The referral, the Justice Department writes, “was made on two bases: evidence that classified records had been stored at the Premises until mid January 2022, and evidence that certain pages of Presidential records had been torn up.” The latter evidence could well speak to intent, if someone were trying to destroy those documents—and, indeed, the referral “included a citation to 18 U.S.C. § 2071” on that point.

The next step in the story involves the FBI’s discovery, while pursuing the referral from the Archives, of “evidence indicating that even after the Fifteen Boxes were provided to NARA, dozens of additional boxes remained at the Premises that were also likely to contain classified information.” In other words, Trump’s team didn’t hand over everything to the Archives when the agency came looking. Perhaps there’s an innocent explanation here—an honest mistake made by Trump and his team about how much material was held at Mar-a-Lago and where it was stored. But it’s clear that the department has its doubts.

Indeed, this discovery by the FBI set off a chain of events in which the Mar-a-Lago camp seems to have repeatedly been less than forthcoming in its interactions with the government. The filing describes so many instances of apparent misrepresentations by Trump’s team to the federal government that it’s difficult to describe them all.

Following the FBI’s discovery of additional classified material possibly held at Mar-a-Lago, the Justice Department obtained and delivered a grand jury subpoena for “ny and all documents or writings in the custody or control of Donald J. Trump and/or the Office of Donald J. Trump bearing classification markings [list of classification markings].” When the bureau arrived to pick up those documents on June 3, Trump’s “custodian of records”—unnamed in the filing, but reported by the New York Times to have been Trump lawyer Christina Bobb—provided a signed letter stating that

a. A diligent search was conducted of the boxes that were moved from the White House to Florida; b. This search was conducted after receipt of the subpoena, in order to locate any and all documents that are responsive to the subpoena; c. Any and all responsive documents accompany this certification; and d. No copy, written notation, or reproduction of any kind was retained as to any responsive document.

All of these statements appear to be at least partly false.

Counsel for Trump also informed the bureau that all of the records transported to Mar-a-Lago from the White House had been kept in one particular storage room at the resort and that “there were no other records stored in any private office space or other location at the Premises and that all available boxes were searched.”

This also appears to be false. As the filing states, the FBI later “uncovered multiple sources of evidence indicating that the response to the … grand jury subpoena was incomplete and that classified documents remained at the Premises, notwithstanding the sworn certification made to the government on June 3.”

During the bureau’s August search, agents found additional documents with classification markings—meaning that the letter signed by the custodian of records was incorrect in stating that “any and all responsive documents” had been turned over to the FBI. What’s more, the FBI found additional documents in an area of Mar-a-Lago called the “45 office,” described in the search warrant as “the former President’s office space”—that is, outside the storage area where Trump’s counsel said all material from the White House had been kept.

The Justice Department also casts doubt on the signed assertion that “a diligent search was conducted of the boxes that were moved from the White House to Florida,” stating,

In the storage room alone, FBI agents found 76 documents bearing classification markings. … That the FBI, in a matter of hours, recovered twice as many documents with classification markings as the “diligent search” that the former President’s counsel and other representatives had weeks to perform calls into serious question the representations made in the June 3 certification and casts doubt on the extent of cooperation in this matter.”

Again, perhaps these were good-faith mistakes by Trump’s team rather than intentional efforts to hold on to sensitive documents or obstruct the FBI’s investigation. But the Justice Department also includes details that look a great deal less innocent, and could go some way toward proving intent under the relevant statutes.

When the FBI first arrived to obtain the boxes in the storage room after serving the initial subpoena, for example, “the former President’s counsel explicitly prohibited government personnel from opening or looking inside any of the boxes that remained in the storage room, giving no opportunity for the government to confirm that no documents with classification markings remained.” (This account differs from the version of events put forward by Trump’s legal team, which has portrayed Trump as obliging to investigators and described the FBI as having conducted an exhaustive search of the storage room.) This would be consistent with Trump’s team trying to keep the bureau from discovering additional responsive material. What’s more, “The government also developed evidence that government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room and that efforts were likely taken to obstruct the government’s investigation.”

The Justice Department also notes conduct by Trump’s team indicating some level of knowledge that the material in question was classified. The department describes how, when handing over documents in response to the initial subpoena,

neither counsel nor the custodian asserted that the former President had declassified the documents or asserted any claim of executive privilege. Instead, counsel handled them in a manner that suggested counsel believed that the documents were classified: the production included a single Redweld envelope, double-wrapped in tape, containing the documents.”

That’s potentially significant, given Trump’s later assertions that he had unilaterally declassified the information in the relevant documents during his time in the White House. (That said, it’s not clear that it would be necessary for the documents to be classified in order for the department to bring criminal charges.)

What about Trump’s own conduct? Reporting has indicated some level of knowledge and involvement by Trump in holding onto the documents in the first place when the National Archives came looking for them. According to the New York Times, “Mr. Trump went through the boxes himself in late 2021”—that is, before the Archives collected some of the material—“according to multiple people briefed on his efforts, before turning them over.” The Times also wrote that Trump “resisted” calls to return material to the Archives in 2021, “describing the boxes of documents as ‘mine.’” CNN has reported that after the Archives took the first tranche of material—which contained classified information—Trump began “obsessing” over arguments that he should not have turned over the documents and became “increasingly convinced that he should have full control over records that remained at Mar-a-Lago.”

The Justice Department’s filing is strikingly quiet on the question of how much, as the phrase goes, the former president himself knew and when he knew it. Indeed, it seems careful to avoid discussing Trump’s conduct at all.

But there are indications nonetheless that Trump may have had some degree of personal involvement in holding onto the documents. Most obviously, the department states that the FBI seized material in “the former President’s office.” In a footnote, the department also describes “the contents of a desk drawer that contained classified documents and governmental records commingled with other documents”—including three expired passports belonging to Trump—and notes that “he location of the passports is relevant evidence in an investigation of unauthorized retention and mishandling of national defense information.” One way to read this might be that classified documents weren’t just in a desk in Trump’s office; they were in a desk in Trump’s office along with other personal documents belonging to him. That doesn’t prove knowledge or intent on Trump’s part, but it’s certainly suggestive of his own personal involvement in the mishandling of the material.

The first conclusion from this extraordinary recitation is that the former president is in serious legal jeopardy. The department could have made all of the legal arguments that follow its factual account with a much more minimal factual presentation. It chose to tell this story. It chose to tell it in an open filing. It chose to make a series of serious imputations about the manner in which the former president and his team had behaved. It chose to include specific facts that suggest that Trump himself had engaged in misconduct. And it chose to lay all this out in a fashion that will make the department look very foolish indeed if the investigation now comes to nothing. The Justice Department does not do bravado, as a general rule. For it to so confidently detail the history of its investigation and the interactions that have driven it suggests a high degree of confidence on where this is heading.

As former Mueller investigation prosecutor Andrew Weissmann put it on Twitter: “DOJ BIG PICTURE: you don’t make a filing this strong, bold, and factually accusatory if you don’t have every intention to indict.”

That said, don’t expect things to move quickly from here. Part of the reason for this involves the forthcoming midterm elections. Reporting has suggested that Attorney General Merrick Garland is “deeply wary” of any public statements that may be perceived as impacting their outcome. Hence the department may well wait until those elections are complete before taking any further major steps, if it can. But the department’s own story in this filing suggests that the investigation is going to take some time. The reason for this conclusion is that the filing identifies a lot of investigative threads that a serious probe will need to address before the department begins making prosecution decisions.

The department, for example, refers to its having “developed evidence that government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room and that efforts were likely taken to obstruct the government’s investigation.” Before it brings a case against anyone—Trump or anyone else involved in the withholding of classified documents—the department is going to want to forensically reconstruct the movement of every document it can from the storage room. That means interviewing every single person involved. It means reviewing all camera footage, to the extent that hasn’t already been done. It means figuring out why some documents were returned to the government early on, others only later in response to a subpoena, and still others not at all—until the FBI showed up with a search warrant.

With respect to the material found in Trump’s office and his desk, the investigation is likely going to try to figure out how it got to those places. Did “a desk drawer classified documents and governmental records commingled with other documents” because Trump himself stashed them there with his own stuff, or for some less personally incriminating reason?

Perhaps most importantly, the department is going to want to understand, in as much detail as humanly possible, who precisely is responsible for what. Did Trump’s lawyers file a false certification as to the completeness of their response to the subpoena and the supposed diligence of their search because they were lying, or because they were misled by others at Mar-a-Lago—and if the latter, who precisely misled them? When the “government ... developed evidence that government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room,” who precisely concealed and removed what specific documents, and at whose direction did they do so?

Many of these questions come back to the same big unknown: To what extent was former President Trump personally and knowingly involved? To be certain, the Justice Department has already described a certain amount of circumstantial evidence that he was, ranging from the documents found in his personal office to the fact that they were intermingled with his expired passports and other personal effects. And the press, as quoted above, has gone significantly further. What’s more, the fact that Trump’s employees accepted subpoenas and issued sworn statements in the name of his personal office does not help his case either. But before it takes a step as controversial as indicting a former president, the Justice Department is likely going to need the sort of clear and inconvertible evidence of Trump’s involvement that is only likely to come from witness testimony.

Perhaps some of the multiple witnesses that the FBI referenced in its search warrant affidavit have already provided such testimony. It’s impossible to know, as both the Justice Department and the magistrate judge remain assiduously committed to withholding any details that might give a hint as to the witnesses’ identities, in order to prevent their identification and intimidation by Trump’s supporters. If not, however, the department is likely to turn to those with such knowledge who have not yet come forward but may prove willing if provided the correct incentive: those members of Trump’s staff who may have received and executed his instructions and thus are now facing potential criminal charges themselves. For this reason, the first wave of criminal indictments, if and when they come, may not focus on Trump himself but those around him, which may in turn encourage them to point toward others who are even more culpable.

In other words, while the FBI may already know the answers to some of these extant questions, others are just as certainly the subject of active investigation following the execution of the warrant. The Justice Department will likely not proceed until it has satisfied itself that it has addressed them all to the maximum extent possible.

In sharp contrast to the factual recitation that precedes it, the legal arguments in the Justice Department’s brief are largely predictable and uninteresting. Nonetheless, the manner in which the Justice Department dismantles Trump’s arguments seeking the appointment of a special master warrants some brief discussion.

In many ways, the arguments that Trump lays out in his Aug. 22 motion seeking the appointment of a special master are tied up with his efforts to frame the FBI’s search as a partisan abuse of power. He argues that the search warrant was overbroad in allowing the seizure of personal effects located alongside presidential records, boldly accuses the government of violating the Presidential Records Act by ignoring his statutory rights to control his own presidential records, suggests that these deficiencies warrant suppression of any seized evidence under the Fourth Amendment, and closes with the telling assertion that “the government has long treated President Donald J. Trump unfairly.” On these grounds, he demands a more detailed accounting of what was seized, argues that a special master should be appointed to ensure that any documents seized are not subject to relevant privileges, motions for a “protective order” directing the Justice Department to cease any review of the seized materials, and insists that the various evidence taken beyond the scope of the search warrant be returned to him.

In responding to these arguments, the Justice Department does not mince words. It begins by rejecting the proposition that Trump has any standing to challenge the seizure of Trump’s presidential records, as the Presidential Records Act states unequivocally that “he United States”—not the former president—“shall reserve and retain complete ownership, possession, and control of Presidential records.” As for Trump’s arguments that the search was overbroad in that it also resulted in the seizure of some his personal effects, the Justice Department notes that this was expressly authorized by the search warrant—which permitted the seizure of containers and boxes in which presidential records and classified documents were found—and reflects well-accepted investigatory practice, as such associated effects have evidentiary value in that they may reveal how documents were mishandled or who had unauthorized access to them. The Justice Department similarly rejects Trump’s contention that a former president may somehow invoke executive privilege against executive branch officials, and cites the Supreme Court’s 1976 holding in Nixon v. GSA as having rejected a similar argument by former President Nixon in relation to NARA’s predecessor agency on the logic that it was an “assertion of a privilege against the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked.” Given these deficiencies, the department concludes that Trump’s request for a protective order is similarly without legal basis. Moreover, as Trump did not file his legal motion until two weeks after the search took place, the harm was already done, as the investigative team had already reviewed the records; instead, such an order would only inhibit the government’s ability to conduct a damage assessment in regard to what classified information might have been compromised, an interest that outweighed whatever marginal interest Trump could put forward.

The department saved its most reserved arguments for rebutting Trump’s assertion that the appointment of a special master would be warranted to help ensure that any documents covered by attorney-client privilege were not improperly divulged. The Justice Department acknowledged that some attorney-client privileged documents might have been taken up in the search but argued that this was the case in almost any criminal investigation and asserted that the “taint team” procedure it had laid out in the search warrant—in which a separate team of FBI agents would review any documents recovered from Trump’s personal “45 office” and remove any covered by such privilege before handing them over to the investigatory team—was more than sufficient. Moreover, it noted that other cases in which a special master had been installed for this purpose were usually reserved for searches of law offices or involved far more voluminous material, in which attorney-client privilege was a greater risk. Doing so here would simply be overkill and would delay the investigation unnecessarily. That said, the department seemed to acknowledge that it could not state decisively that no attorney-client privilege was at risk, and that this factor may prove persuasive to a judge intent on providing Trump with every possible benefit of the doubt. On this apparent logic, the Justice Department proposed what a special master’s role should look like if the court does side with Trump—noting most importantly that his or her ambit should be limited entirely to attorney-client privilege, not executive privilege. For this reason, it’s not entirely unimaginable that the Justice Department may ultimately concede to the appointment of a special master, whose work will only further ensure any investigation is not compromised by privilege concerns. The real question then will not be whether a special master is appointed, but what such a person is tasked to do.

The one concession that the Justice Department does seem to make is to Trump’s demand for a more detailed receipt of seized material, which it indicates in a footnote that it has prepared, filed under seal along with its response, and is willing to provide to Trump upon request. Of course, the existence of a (presumably unclassified) more detailed inventory is likely to lead to efforts by the media to secure its release. And Trump himself may feel pressured to back such demands, given his past calls for greater transparency. This in turn may set up another round of Trump’s own actions coming back to bite him, as we suspect the inventory is likely to only further underscore—in clear, undeniable detail—the substantial amounts and types of information Trump put at risk with his actions.

In short, the department has stressed that the investigation is in its early stages and this document—despite its strength—offers a window on why. While it shows a high level of confidence about the integrity of the probe, about the manner in which it was conducted, about the law being on the government’s side, and about the quality and damning nature of the evidence it has already unveiled, it also shows that there’s work yet to be done.

Spread the word