According to new rules that come into force on October 20, foreigners in the West Bank who fall in love with Palestinians must inform Israeli authorities of this romantic interest. This bizarre, nonetheless terrifying news is another testament to how Israel’s apartheid regime seeks to brazenly control our lives and bodies. For me as a Palestinian, it comes as no surprise.

In fact, as many scholars have argued, Israel’s settler-colonial character precisely manifests through such a logic of entitlement – where the state seeks to dominate indigenous bodies and determine the ways they exist in the world – how they live, move, get sick and heal, and how they love and reproduce.

The idea that bureaucrats and officials feel entitled to determine every single aspect of Palestinian life (including whom we love and how we do that) is beyond the concept of control, it is about the institutionalization of a decades-long colonial fantasy about enslaving Palestinian bodies. This logic of entitlement has defined decades of oppression in Israel/ Palestine. Palestinians have long known this and therefore seem less shocked by the new rules. Over the course of my work on reproduction and intimacy politics in Palestine, I have visited several families wrenched apart by Israeli apartheid – children who have never met their fathers, bedrooms abandoned on the Israeli army’s orders, and partners whose access to conjugal togetherness is mediated by a militarized state.

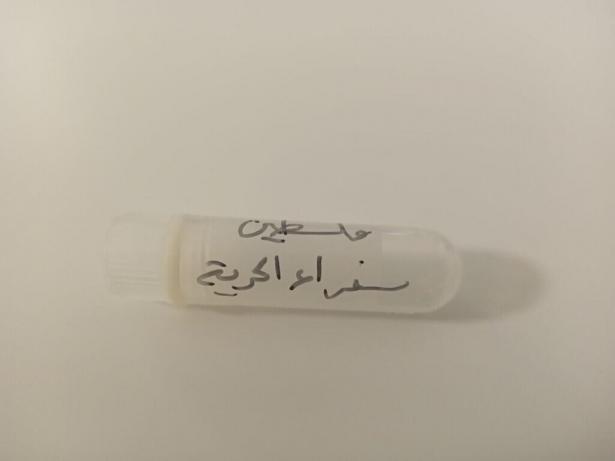

Earlier this year, I conducted interviews in the city of Nablus, to the north of the West Bank. I came across the demolished apartment of a Palestinian prisoner who was arrested a few months after his wedding. While I looked at a rusty bed frame in what used to be the couple’s bedroom, his wife told me that the Israeli army comes every few months to make sure that the apartment remains unoccupied. This same woman was nevertheless able to give birth to her husband’s child, with sperm smuggled from behind bars. “It’s a story of victory that they would never even get,” she told me. A deserted bedroom, rusting furniture, a prisoner now punished and banished; a child who came into the world as an “ambassador for freedom” as the Palestinians call these children. This scene could sum up nearly a century of conflict over intimacy in Palestine. Intimacy, a space of colonial domination, but also of resistance.

Abandoned apartment sealed by the Israeli Army. Nablus 2022. Photo credits: Izzeddin Araj

The above picture, taken on that day last Spring, demonstrates more than merely the Israeli tendency to invade and control every aspect of Palestinian life. It also illustrates how the right to intimacy and love lies at the core of settler-colonialism. Every time I look at the picture, I remember the Hebrew name for the place where Jewish prisoners meet their partners on conjugal visits in Israeli prisons – the ‘love room’. If you are a Jewish prisoner imprisoned for assassinating the Israeli prime minister, you would still have the right to conjugal visitation, which is indeed the case of Yigal Amir who killed Yitzhak Rabin. However, if you are Palestinian, you are doomed to have no room for love. It is that clear and has always been.

It is important to feel shocked by the new rules, as normalizing this oppression should not be an option. Yet, it is crucial to understand that they represent nothing exceptional or incidental and should be understood within the broad context of entitlement and intervention that governs everyday life in Palestine.

The targeting of Palestinian intimacies is not a metaphor. It takes place amidst the material realities of ordinary people and their everyday lives. The colonial fragmentation of Palestine and Palestinian land is an everyday exercise of power, and is most clearly reflected in the systematic separation of our bodies. In one way or another, access to land – a question at the core of settler-colonialism, is manifested, among other things, through access to love. Over the course of my life and work in the West Bank, I have met several partners forced to live apart as a result of these colonial demarcations of land and bodies.

However, there is another side to this story. As Israel seeks to force these people apart, they constantly produce and reclaim forms of togetherness that subvert the distances imposed by this colonialism of borders. Through several intimate forms of resistance, Palestinian bodies have demonstrated what I call ‘counter-demarcation’. There are many examples – like the stories of prisoners whose sperm is smuggled from prisons in Palestine ’48 to the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. This practice extends the imprisoned and bordered self outward and brings their children into the world.

All of this tells us that intimacy is as much a realm of resistance as it is one of domination. One way to understand the Palestinian struggle is as a struggle for togetherness. And one way to read the colonial regime is as an attempt to tear Palestinians apart, from the world, but also from each other. I am appalled by news of the recent policy, but also know, as all Palestinians do, that it is only a small part of a long, ongoing story.

Izzeddin Araj is a Palestinian researcher, journalist, and Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at IHEID in Geneva, Switzerland.

Mondoweiss is an independent website devoted to informing readers about developments in Israel/Palestine and related US foreign policy. We provide news and analysis unavailable through the mainstream media regarding the struggle for Palestinian human rights.

Mondoweiss is only able to continue with the support of its readers. The website is part of The Center for Economic Research and Social Change, a 501(c)(3) organization, and contributions to which are tax deductible to the extent provided by law.

You can make an online tax deductible donation here,

Spread the word