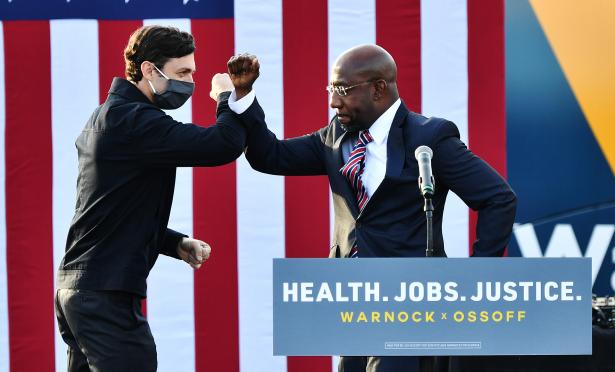

This article is excerpted from an interview conducted by Linda Burnham with four activists in the organizing that won Georgia in the Presidential election of 2020 and two crucial U.S. Senate seats in a Jan. 5, 2021, runoff. The interviewees are Cliff Albright (Black Voters Matter), Adelina Nicholls (Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights), Beth Howard (Showing Up for Racial Justice) and Nsé Ufot (New Georgia Project). The interview is the opening chapter in the book Power Concedes Nothing: How Grassroots Organizing Wins Elections, edited by Linda Burnham, Max Elbaum, and María Poblet. -- moderator]

Nsé Ufot: We are actually a constellation of organizations. New Georgia Project, is a 501(c)(3). New Georgia Project Action Fund is our 501(c)(4) and advocacy arm. New South Super PAC works in the 600-plus counties that make up America's Black Belt from East Texas all the way to D.C. There are tons of counties across that swath that are majority Black and have never had a Black elected official, never had a Black mayor, never had a Black or Latino person serve on school board or city council. The way that we change America is by changing the South and supporting elected officials who come from the communities that we care about.

People probably know us best for registering nearly 600,000 Black and Brown folks to vote in all 159 of Georgia's counties. So there isn't a place in Georgia where the New Georgia Project hasn’t organized, even in the parts of the state that people call Deliverance Country.

Georgia is changing really rapidly. Black and Brown people are going to make up the majority of Georgians and there's this racial voter registration gap. There are 1.2 million African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans and unmarried white women in the state who are eligible to vote, but they're completely unregistered.

Cliff Albright: In 2020 we were trying to expand and go deeper on the work we’d been doing in Georgia for the past three years. We started in one county in Georgia in 2016. Our first county was Sumter County. There was one legislative seat that we were trying to impact. The first $1,000 we raised went into doing some GOTV on election day. Lo and behold, that seat flipped. It was a Republican-controlled seat in a county that is largely Black. Since then, we’ve been expanding county by county, mainly in rural areas, connecting with organizations in places no one could find on the Georgia map.

We connect with folks who are already there, already doing the work. That might be a church group, it might be an NAACP chapter, it might be a youth arts & culture organization. It might be a group that’s not even a formal group. The group of mamas on the corner who, when they need to round up the community, they get it done. Then sometimes people reach out to us. Either way, it’s about that connection with local groups, the existing infrastructure, and then seeing what we can do together.

“SOMETHING DIFFERENT FROM TRADITIONAL ELECTORAL POLITICS”

Adelina Nicholls: In 2020… we started first with civic engagement, get-out-the-vote, informing about the dates and candidates. We organized, in collaboration with SONG and Mijente, community forums and candidate forums. Our initial approach was to target two counties: Cobb and Gwinnett counties. Both counties had 287(g) programs [agreements between the Department of Homeland Security and local law enforcement] with devastating consequences in the Latino or undocumented community. We canvassed around 140,000 doors in both counties reaching Latinx and also communities of color, explaining what 287(g) was, and that we need the support to kick out those sheriffs.

At the end of the day, in both counties we were able to kick out both sheriffs, putting in place for the first time in the history of those counties, two Black sheriffs. Of course, one of the things they did was deliver the end of 287(g).

For more than twenty years we have built this network called comites populares (people’s committees) around the state–a network where more than 19 groups in the state of Georgia have helped us to mobilize, getting out the Latinx vote, in particular in rural communities that nobody cared about. We started to have these young voters—18, 19, 20, 25—who, for the first time, wanted to be involved. With the general elections we canvassed more than 330,000 doors statewide, reaching every single Latinx door in the state.

We wanted to do something a little different from traditional electoral politics, which tells us we only need to reach those who are able to vote. We thought “No way!” Many [in our community] do not vote. So, we continued trying to motivate and create this movement among the Latino community.

Beth Howard: We are trying to build large-scale base-building work centered in grassroots organizing. We're layering base-building with electoral work through SURJ Action. As white anti-racist folks, being in these communities that we've often overlooked, we have really seen the vacuum that's left. The right has invested so much money in making sure that poor and working-class white people will choose the side of the oppressor. And so we're trying to build this base. We do that by creating the kind of welcoming space that is centered in working-class community.

For the runoff election, I was with part of our field team in rural north Georgia. There's really no progressive infrastructure there, or if there is, it's pretty small. We had a robust phone-banking program in the general election that we continued into the runoffs. Between the general and the runoff, we made 1.8 million calls into Georgia to do persuasion, turnout, and deep listening.

A lot of what I helped strategize around was our rural canvassing. We were knocking on doors that are largely ignored by the Democrats. We really wanted to educate our canvassers and our members, preparing us to go out and be in our culture, love on people, see them in their dignity and embrace the culture as opposed to it being something that is wrong or something we need to change. That's a challenge, and it's so rewarding. Time after time we would hear people , “I cannot believe you came out here! No one comes out here to talk.”

“HIGH QUALITY, FACE-TO-FACE CONVERSATIONS”

Nsé Ufot: Our most sophisticated, most effective tactic is high-quality face-to-face conversations. We go door to door, we have in-person meetings in church basements and in housing projects and college campuses all over the state of Georgia. And quarantine didn't allow us to do that. And so we had to get creative. How do we recreate those high quality conversations in a technologically mediated environment? A huge challenge, and I don't think that we’ve figured it out yet.

One of the things that we were really proud of is that all of our meetings had always had food, always had music, always had childcare. We couldn't meet in person, but we would send people Uber Eats and DoorDash if we needed people to meet with us virtually. Fifteen minutes before we began, we'd make sure that there was food delivery at your house to try to recreate the experience we had if people were coming to meet us at the office. We kept our phone banks and text banks alive. But instead of texting people and asking if they registered to vote or reminding them about the upcoming election, we would ask them how they were doing and if they knew where to go to get help, if they needed it. So we were keeping our list warm, but we led with our humanity.

“THE SOUTHEAST HAS BEEN NEGLECTED”

Adelina Nicholls: For many years, in particular with us here in the Latino community, the Southeast of the United States has not been funded; organizations like ours that didn’t have participation in electoral politics. We saw the attention going just to the electoral part, diminishing the importance of grassroots organizing.

I did hear many years ago that the coalition between Black and Brown was “Mission Impossible.” I don’t think so. I think the new generations of Latinos, but also the Black communities, have opened up. I do believe we have shown, in terms of last year, that this is possible. Communities of color made the impossible possible.

CLIFF ALBRIGHT: The power of culture in our work is something we knew was important prior to 2020. In 2020, it went to a whole different level. We were able to use music and culture and faith and food, and traditions. One of the most powerful activities that we did was, we were giving out food boxes during the holiday season, which included fresh produce, fresh vegetables grown largely by Black farmers in the area. December 31 was the last day of early voting. Well, what are people thinking about on New Year’s Eve? They’re thinking about New Year’s Day, which in our community is a tradition around cooking collard greens and black-eyed peas. Folks are getting ready for New Year’s Day. Why don’t we help them by giving out fresh collards and black-eyed peas and why not throw in a few boxes of cornbread. But we’re going to do it at locations that are across the street from the early vote polling place. As people are going through getting their box of goodies for their New Year’s meal, we’re like “Hey, by the way, today’s the last day of early voting. How about you go across the street and go vote.” And we did this in 30 counties simultaneously in one day. We believe this is part of the reason the Georgia legislature made sure to forbid giving out food and water to people as they were waiting in line. That didn’t just come out of no place.

Another lesson, there was a lot of attention being paid to Georgia, and a lot of our groups got more money than we get in a typical election year. Money is not the end all and be all. But [for our] groups, having some extra cash matters!

All of that—the importance of investment, the importance of unity, the importance of using culture to turn out voters, and the importance of focusing on the issues, not on personalities—all of that is part of the secret sauce.

TOWARD 2022 AND 2024: “PLAYING FOR KEEPS”

Nsé Ufot: Cconservative Republicans are playing for keeps. The violence that we are seeing in this moment by white bad actors is being underreported. I'm really proud of all that we have been able to accomplish. People don't recognize how remarkable it is because they don't appreciate the violence that we are routinely subject to in trying to do this work. And I'm talking about state violence that includes press conferences where they put my photo up and call me a criminal and accuse us of participating in voter registration fraud. Georgia's anti-voting bill created five new voting crimes, and two of them are felonies.

What I need people to know is that what we are building is super innovative. It's designed to meet the threat of the moment. The level of sophistication of these white supremacists and their campaigns has increased. The response from movement and justice organizations has to meet that sophistication with its own sophistication. That's why we build video games. That's why we focus on misinformation and disinformation and how it's poisoning the information wells and social media.

We love ourselves, we love our families, we love our communities. That's a renewable resource and that's what we use to power our campaigns. As awful as things are, as angry as we get, as hypocritical as our government is, the thing that keeps us going back to work is that we do this work in community. You've seen people go to the ends of the earth for their loved ones. And that is what we're willing to do for Black families in Georgia.

Spread the word