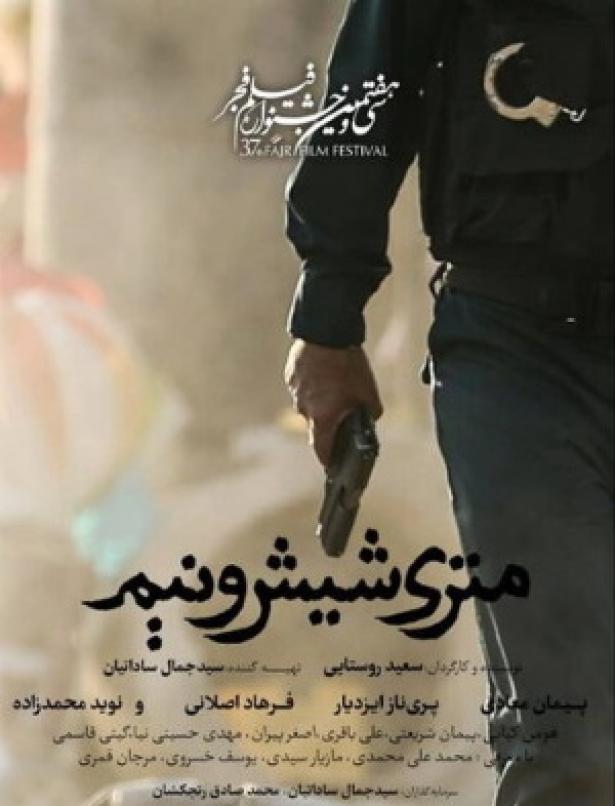

This increasingly nerve-jangling narco policier from Life and a Day writer-director Saeed Roustayi, who has since made the feted 2022 Palme d’Or contender Leila’s Brothers, was hailed as Iran’s highest-grossing non-comedic domestic film. Not that Law of Tehran (AKA Just 6.5), which won the audience award at Iran’s Fajr film festival back in 2019, is without a pointedly nihilistic streak of jet-black humour. For proof, check out the horrifyingly absurdist opening salvo: a drug bust that turns into a breakneck, on-foot chase sequence, climaxing in a lethal disappearing act that combines the vérité grit of The French Connection with the physical slapstick of Buster Keaton. Really. It’s a deliberately bewildering cocktail of brutal tragedy and gallows farce that runs throughout this very arresting feature.

Playing out amid the human squalor of Tehran’s addiction epidemic, this festival favourite seems even more urgent now than when it first opened in Iran four years ago. Iranian American screen polymath Payman Maadi (who made such an impact in films such as Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation) is Samad, a cop waging an apparently unwinnable war on drugs in the Iranian capital. Having rounded up a vast community of addicts living and dying within a hellscape of giant concrete pipes, Samad and his deputy, Hamid (Houman Kiai), treat their captives like cattle, stripping and humiliating them, herding them from one overcrowded prison space to the next.

I struggle to remember a film in which the thin blue line between cops and criminals is more vividly dramatized.

From a house where a suspected dealer’s wife and children cower in terror, to an airport where swathes of human flesh are used to mask drugs from X-ray machines, there’s nothing glamorous about this world. The self-destructing Khakzad may be holed up in a swanky apartment, but he’ll soon find himself fighting for breathing space among the living dead who are hooked on his products. Yet even as Roustayi confronts us with the grotesque toll of Khakzad’s trade, so the film does a nimble two-step that begins to humanise its central villain just as Maadi’s relentless cop starts to alienate everyone around him.

Lurking in the background is the omnipresent spectre of the death penalty, a punishment so severe that it ought to dissuade anyone from breaking the law. Yet as Samad ruefully observes, the truth is quite the opposite; no matter how harsh the authorities’ treatment of dealers and addicts becomes, their numbers continue to soar. Perhaps the punishment is the problem? When you’re faced with odds such as these, what do you have to lose?

Collapsed marriages and lost children litter the plot, increasing the sense that everything is teetering on the brink of failure. It’s a credit to Roustayi’s deft storytelling that somehow he manages to bury this unpalatable pill within the fabric of a gripping drama that doesn’t preach but merely suggests – leaving it up to the audience to decide who, if anyone, are the heroes.

-

Law of Tehran is in cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema

Spread the word