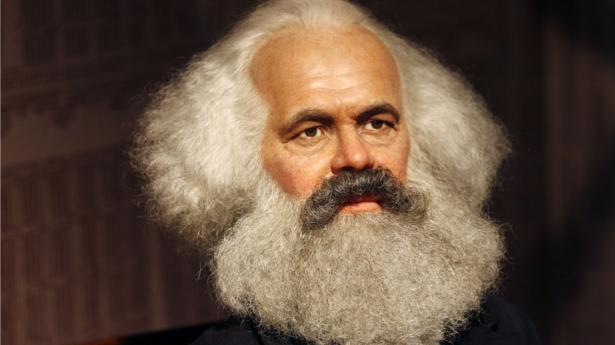

Karl Marx deserves a better caliber of critics. I’ve thought that many times in the last few years, but perhaps never more so than in March when I saw the conservative James Lindsay post a picture of himself pretending to pee on Marx’s grave in London.

I couldn’t help but notice the lack of any actual stream of urine in the picture. In a way, that made it a perfect metaphor for the Right’s approach to their greatest intellectual adversary. They’re making a show of desecrating his grave. But they know too little about his ideas to even make contact with the target of their critique.

Lindsay, Levin, Kirk, and Peterson

Lindsay isn’t some obscure right-winger. He’s a globally prominent figure. He testifies before state legislatures explaining why they should ban “critical race theory,” which he sees as Marxism in disguise. His book, Race Marxism, was a bestseller.

So was Mark Levin’s book, American Marxism. Levin was never quite as popular as his colleagues Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity, but his talk radio show has blared out from hundreds of AM stations around the United States for many years. Originally, I was slated to cowrite a review of American Marxism with Matt McManus, but after many attempts to get through it, I ended up admitting defeat and letting Matt write it by himself. The book feels like the transcript of an endless, breathless, incoherent rant. I’d be surprised if Levin even cracked open Marx’s magnum opus, Capital.

Right when I was trying and failing to ingest Levin’s book, I did a public debate with one of conservative media’s most omnipresent figures: Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk. At one point, Charlie asked me what I thought about Karl Marx. I responded that while I didn’t think Marx was right about everything, he was right about a lot of important subjects — in particular, his theory of history.

Charlie seized on that to say Marx’s theory of history was “basically Hegel’s” — after all, he said, wasn’t Marx the “president of the Young Hegelians”?

This could hardly be more wrong. G. W. F. Hegel had an “idealist” theory of history — he saw it as driven by the progressive self-realization of what he called the “World Spirit.” Marx did start out as a Young Hegelian, but this was the name of a philosophical current, not an organization with membership cards and a president! More substantively, Marx — though deeply influenced by Hegel’s methodology — came to reject idealism in favor of a “materialist” theory of history in which the primacy is given to economic factors: the “forces of production” and “relations of production.”

Lindsay, Levin, and Kirk aren’t the only prominent conservatives who insist on prattling on about Marx despite not knowing the ABCs. In Jordan Peterson’s 2019 debate with the Slovenian Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek, Peterson said that he’d prepared for the debate by rereading the Communist Manifesto for the first time since he was eighteen.

That in itself was an astonishing admission. Here you have someone who wrote mega-best-selling books that contain strenuous denunciations of “Marxism” admitting that he hadn’t read the Communist Manifesto — a short pamphlet that can be consumed in an afternoon — in decades.

But even more striking was how little understanding Peterson seemed to have of what he’d read. He expressed surprise that Marx and Friedrich Engels “admitted” capitalism had spurred more and faster economic development than any previous system — when in fact they devote pages to the observation because it’s a crucial part of their analysis. And in a swipe at the first sentence of chapter one of the Manifesto, about how all “hitherto existing history” is a “history of class struggle,” Peterson argued:

Marx didn’t seem to take into account . . . that there are far more reasons that human beings struggle then their economic class struggle. Even if you build the hierarchical idea into that (which is a more comprehensive way of thinking about it), human beings struggle with themselves, with the malevolence that’s inside themselves, with the evil that they’re capable of doing, with the spiritual and psychological warfare that goes on within them. And we’re also actually always at odds with nature, and this never seems to show up in Marx . . . . (my emphasis)

But the way that humans are “at odds with nature” is right at the heart of Marx’s theory of history! Marx thinks the “legal and political infrastructure” of any society is downstream from the “relations of production” — i.e., the relationship between the immediate producers (whether slaves or peasants or modern wage workers) and the class in charge of the production process (whether slaveowners or a feudal aristocracy or capitalists). And Marx thinks these relations are themselves, in an important way, downstream from the level of development of the forces of production — roughly, the capacity of a society to transform what we get from nature into products that meet human needs.

Marx’s Theory of History

Marx’s account of history goes something like this:

Early hunter-gatherer societies lacked a class of nonproducers because there wouldn’t have been enough to eat if there was a ruling class that wasn’t out hunting or gathering. Absolute scarcity reined. The agricultural revolution boosted human productive capacity to the point where it could support a ruling class, but only if some of what was created by the “immediate producers” was directly taken by force — as in modes of production like slavery and feudalism.

The development of modern industry creates (and requires) a different mode of production where the immediate producers are “doubly free”— free in the sense of being free citizens with a legal right to move around and make contracts with any employer who will have them, and also “free” from any means of supporting themselves except for selling their working time to a capitalist employer — so they end up submitting themselves to a new ruling class. And yet, Marx says, capitalism pushes the forces of production to such advanced heights that there’s a new possibility: workers themselves can take over the means of production and create a better future.

Marx is very clear that having to work to transform the deliverances of nature into human “use values” is a necessity originally imposed by nature and not by any particular social system. But those systems force immediate producers not just to produce to meet their own needs, but also to spend additional hours doing unpaid labor on behalf of the ruling class.

This happens right out in the open in a system like feudalism, where serfs are legally forced to spend part of their time toiling in the lord’s field instead of the little plot of land with which they feed themselves and their families. But Marx thinks the same thing happens in a disguised form in capitalism — officially, you’re being paid for every hour you work, but in practice some of the work you do creates the goods and services that are sold to pay your own wages, and some of it goes toward your boss’s profits. Under socialism, when “free associations of workers” run the show, workers themselves would get to decide how the proceeds of their labor would be divvied up. Some portion would go to nonproducers like children, retirees, and those unable to work, but none would be taken by a capitalist class.

One of the crucial differences between Marxism and earlier forms of socialist thought is that Marx doesn’t see capitalism as an avoidable moral mistake. However ethically abhorrent, and however desirable surpassing it might be, capitalism to Marx is a necessary stage of historical development. That’s why Marx and Engels devote such space at the beginning of the Manifesto to talking about the amazing ways the forces of production have been developed under capitalism. For the first time, there’s the possibility of something better — not the combination of freedom and material hardship experienced by early hunter-gatherers, or even by independent small farmers who have to work all day every day just to produce the necessities of life, but an egalitarian and democratic version of high-tech modernity.

There are real criticisms you can make of Marx’s vision. Some people argue, for instance, that to deal with the climate crisis we need to roll back our industrial infrastructure — we need “degrowth.” I disagree, but that’s at least an argument with people who know what they’re arguing against. That’s not the argument we’re having with the Right.

One way you can tell as much is that they’ll cite the failures of authoritarian state socialist governments — starting with the Soviet Union — as a great refutation of Marx. But what did Marx actually say about Russia?

As Steve Paxton points out in his book Unlearning Marx, Marx specifically wrote that it would be impossible for undeveloped, semifeudal Russia to skip capitalism and leapfrog into the socialist future unless a revolution in Russia was accompanied by a revolution in industrialized western Europe. Don’t get me wrong. I know twentieth-century Marxists would have preferred to see a politically democratic and materially prosperous form of socialism take root in the Soviet Union than see Marx’s theory confirmed. But that theory being confirmed is exactly what happened.

Better Critics, Please

Iactually want better critics of Marxism. Everyone should want that. Anti-Marxists should want it because they clearly think criticizing “Marxism” is important — the contemporary right never shuts up about it! — and you can’t do that effectively if you don’t know what Marx’s theory of history even is. Marxists should want it because the best version of our view will come through engagement with the smartest criticisms. I want critics who can make us think hard about our premises and revise the parts that need revising. That’s how intellectual progress works.

Give me conservative intellectuals who’ve carefully read Marx — who can formulate critiques that make me squirm. I might not like it in the moment, but we’ll all benefit from the process.

Instead, we get the kind of right-wingers who say environmentalists are secret Marxists and that the crypto-Marxist plan is to make us all eat bugs for the sake of conserving the environment. Or who express confusion about why Marx and Engels talk about rapid economic development under capitalism in the Communist Manifesto. Or who think Marx thought Tsarist Russia could skip to socialism. Or who, dear God, say things like, “We’re also actually always at odds with nature and this never seems to show up in Marx.”

Real critics can serve a useful purpose. The would-be grave desecrators, though? They’re just wasting everyone’s time.

Ben Burgis is a Jacobin columnist, an adjunct philosophy professor at Rutgers University, and the host of the YouTube show and podcast Give Them An Argument. He’s the author of several books, most recently Christopher Hitchens: What He Got Right, How He Went Wrong, and Why He Still Matters.

Spread the word