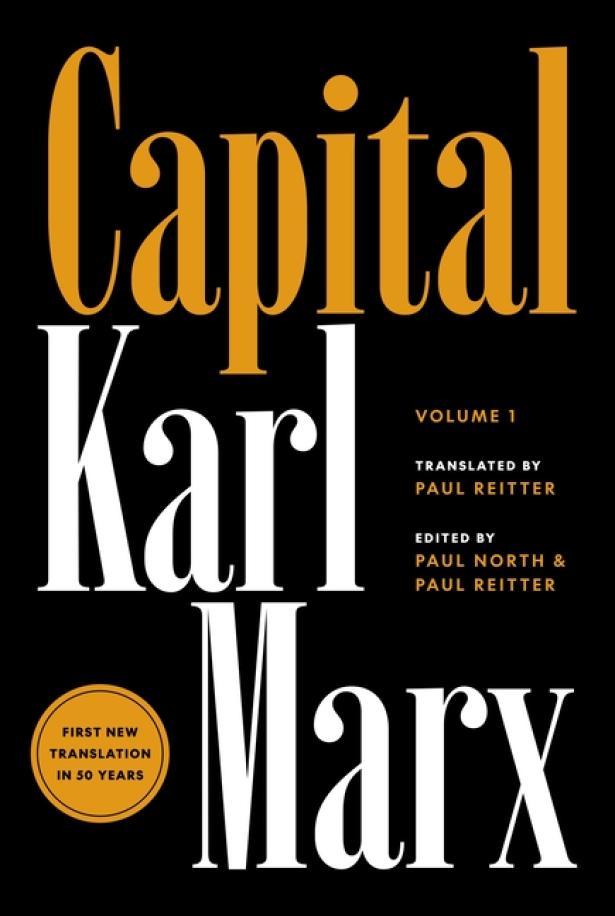

Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1

Karl Marx

Edited and translated by Paul Reitter

Edited by Paul North

Foreword by Wendy Brown

Afterword by William Clare Roberts

Princeton University Press

ISBN: 9780691190075

The new translation by Paul Reitter of Marx’s most important work has two main things going for it.

Firstly, it has a direct relationship to a determinate original text by Marx, the 1872 second German edition. This means that it is very straightforward to compare the translation with what Marx actually wrote. This is in striking contrast with what we find with the 1976 Ben Fowkes translation, which is based on a mish-mash of the 1883 third German edition (edited by Engels), the 1872-75 French translation (which Marx supervised) and the 1890 fourth German edition (edited by Engels). As is evident to a careful reader of Fowkes’s version, he does not for the most part directly translate Marx; instead, he modifies the 1887 English translation by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling in the light of the 1890 German text. Moore and Aveling’s work was supervised by Engels, and he got them to translate the 1883 German edition but also to use the 1872-75 French translation to clarify and amend what Engels referred to as the more ‘difficult passages’. Many but by no means all of these changes were then incorporated in the 1890 German edition. A striking example: in the third paragraph of chapter one, §1, Fowkes has Marx say: ‘The discovery of the manifold uses of things is the work of history’ (underlining added for emphasis). However, all four German editions (1867, 1872, 1883 and 1890) give geschichtliche That, namely ‘historical act’. So why does Fowkes have ‘the work of history’? Well, it is the result of his copying Moore and Aveling. And they have ‘work of history’ because they are rendering the French: une oeuvre de l’histoire. And why not? Thomas Kuczynski, in his 2017 Neue Textausgabe, changes the German text to follow the French, and so we read there ein Werk der Geschichte! Anyway, this is all just initially to indicate the difficulties of working out what it is that Fowkes’ translation is based on, and therefore the benefit of now having an English text which directly relates to a stable original.

Secondly, the new translation improves on Fowkes in a number of respects. One notable instance is the use of ‘gelatinous blob’ for Marx’s characteriation of value as eine bloße Gallerte of undifferentiated human labour (a phrase he uses seven times in chapter one). This is indeed what Gallerte means (Moore and Aveling give ‘a mere congelation’, Fowkes ‘merely congealed quantities’). However, the editors do not appear to appreciate quite how appropriate this term is. Gelatin is a translucent, colourless, flavourless food ingredient, traditionally produced by boiling up animal carcasses. So it is both the product of a kind of process of abstraction and itself manifests abstractness (absence of determinate qualities, also its ability to take on different forms). The editors comment that ‘the image of “gelatinous blobs” doesn’t neatly cohere with the idea of “ghostly ”’ Marx associates with it (796). But I think this is mistaken: Marx opts for ‘gelatin’ precisely because it can suggest the spectral and phantasmagorical. We can see this in the term ‘ectoplasm’, which was coined later in the nineteenth century by spiritualists to refer to the ‘ghostly objecthood’ manifested in spiritualist séances: Arthur Conan Doyle defined it as ‘a viscous, gelatinous substance which appeared to differ from every known form of matter in that it could solidify and be used for material purposes’.

Some other examples of where the translation is to be commended: it is good to have entpuppt properly rendered in the opening sentence of chapter four, §2 (‘Contradictions in the General Formula’): ‘The form of circulation where money emerges from its chrysalis as capital contradicts all the laws we have explicated up to now.’ (130, underlining added for emphasis). Fowkes simply has this as ‘is transformed into’. This is all the better as the metaphor is then nicely picked up again in the final paragraph of §2, where Marx refers to the ‘capitalist in larval form ’, who ‘both must, and cannot metamorphose into a butterfly ’ (140). I also like the fact that Marx’s exclamation marks are shown in the ‘freedom, equality, property and Bentham’ passage (149, omitted in the Moore/Aveling and Fowkes versions). These are just some of the many places where we find the translator treating Marx’s German text with subtlety and care.

However, these positive features are outweighed by many deficiencies.

The most problematic feature is the mangling of specific terms. An especially striking example is the handling of the German word Personen. As we all know, having read Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, the term ‘person’ has the very particular meaning of an individual with property rights, who relates to others by means of the things each of them own. It is not equivalent to ‘human being’, as contemporary usage, especially in North America, might suggest. But the new translation regularly uses ‘person’ for Menschen and ‘people’ for Personen (as well as ‘person’). This occurs most disastrously in the very opening paragraph of chapter two, where Marx introduces the concept of the person: here we find both mistranslations. So we read: ‘Commodities are things and thus defenseless against people . If they are unwilling to belong to someone, that person can use force – in other words, simply take them.’ (60) The first sentence correctly uses ‘people’ for Menschen. But in the second sentence the translator supposes that Marx’s use of the pronoun er can be rendered as ‘that person’. But the whole point is that behaving in this way is not what persons do, because persons relate to each other as rightful owners of property! This is what Marx goes on to say in the next sentence: ‘Commodity owners can put things into a relation as commodities only when they treat one another as people whose wills reside in those things, and an owner doesn’t acquire another’s commodity unless both parties are willing.’ (60) But again the translation is wrong: it should be ‘persons’ here, not ‘people’! And this flip-flopping of ‘people’ and ‘persons’ for both Personen and Menschen continues throughout. The most egregious example comes in chapter three, §2, where Marx writes that the contradictory character of the commodity is manifested in the Personificirung der Sache und Versachlichung der Personen. Fowkes gives this as ‘the conversion of things into persons and the conversion of persons into things’, providing the German in a footnote. The new translation has ‘the personification of things and the thingification of people’ (88). This is terrible. Why wreck Marx’s chiasmus (one of his favourite rhetorical devices)? I suspect that the translator/editors think that this ‘thingification’ is meant to be pernicious to us as ‘people’, as human beings, amounting to ‘reification’ (see lv, lxxvi). But Marx’s underlying point is that to be a person is already to be ‘thingified’, to be represented in and through property; the term does not refer to some condition or status that is negated by commodification. It should be added that Fowkes is by contrast entirely reliable when it comes to rendering Personen.

Another term which is badly handled is Wissenschaft, that is, ‘science’, as with the Latin scientia. As is well known, the German word retains the original extension, whereas in English since the nineteenth century it has narrowed to refer to what are therefore pleonastically called the natural sciences. All this is fairly easy to explain and bear in mind. But the new translation makes a real mess of the term, rendering it as ‘scholarship’, ‘systematic scholarship’, ‘systematic knowledge’, ‘science’, ‘science and scholarship’ and at one point ‘science and systematic scholarship’ (!). An endnote ‘explains’: ‘The word rendered as “scholarly” is “wissenschaftlich.” It can mean “scientific,” that is, “having to do with natural science,” and also “systematic,” in the sense of truly rigorous and properly self-reflective with regard to scholarly method.’ (793) This is not right: wissenschaftlich in Marx’s texts does not mean ‘having to do with natural science’; for that he uses naturwissenschaftlich. And ‘scholarship’ seems too weak. It would have been so much easier and neater just to stick to ‘science’. I suspect that the editors/translator are just uneasy with Marx’s claim to be wissenschaftlich!

Additionally, Marx’s connected use of veräußern and entäußern (and related nouns) does not come over very clearly in this translation. The fact that he uses them as a pair is mentioned in an endnote (813-814), but what the terms mean or how they are translated is not discussed. In the text itself we find them given as ‘to dispose’ and ‘to divest’ respectively, which is fine (and in virtue of being relatively consistent, improves on Fowkes’ variable treatment). But we miss both the sense of their common root and the related fact that entäußern can also be taken as ‘to externalize’, that is, in an alienating manner. In chapter three, Marx writes that ‘Gold in der Hand jedes Waarenbesitzers die entäußerte Gestalt seiner veräußerten Waare.’ This is translated as: ‘In the hands of every other commodity owner, gold is the shape of a commodity that has been disposed of and thereby divested of its original shape’. This doesn’t really convey Marx’s assertion that gold (and therefore money, Geld) is the externalized form of value of each and every commodity.

In addition to these issues with specific terms, there are many other respects in which the new translation is problematic.

The translator frequently chooses to reorganize Marx’s sentences in ways which spoil the sense. Two examples, both from chapter four, can be invoked. The chapter opens with the straightforward statement: ‘Die Waarencirkulation ist der Ausgangspunkt des Kapitals.’ Hard to go wrong, one might think. But the new translation, perhaps striving to avoid the obvious, gives us: ‘Capital begins with the circulation of commodities’ (121). This is far too free. For one thing, Marx’s order re-enacts the very transition from the circulation of commodities to capital, which the book is at this moment conceptualizing. And we really should have Ausgangspunkt correctly conveyed: it means ‘starting point’ or ‘springing-off point’, and as it is used a further eight times in the rest of the chapter (and translated as ‘starting point’), it should be used translated in this way here, at the starting point! Had Marx meant to say what the translator provides, he would have written ‘Kapital beginnt mit der Cirkulation von Waaren’. But he didn’t. (Fowkes, following Moore and Aveling, correctly translates Marx’s German as ‘The circulation of commodities is the starting-point of capital’.)

Second example. In a well-known sentence later on in chapter four, Marx says that ‘Als bewußter Träger dieser Bewegung wird der Geldbesitzer Kapitalist’. Fowkes translates this very cleanly: ‘As the conscious bearer of this movement, the possessor of money becomes a capitalist’ (modifying Moore and Aveling, using ‘bearer’ instead of their ‘representative’). The new version however gives the following: ‘The money owner becomes a capitalist when he acts as the conscious bearer of this movement’. (127). But why reverse Marx’s order in this way? It changes the force of what he is saying, not least because of the unwarranted addition of ‘when he acts’, which suggests a sense of choice on the part of the money owner (I owe this point to Robin Halpin). Had Marx intended what the translator provides, he would have written something like ‘Der Geldbesitzer wird zum Kapitalisten, wenn er als bewusster Träger dieser Bewegung auftritt’. But he didn’t.

Another insistent and annoying feature of the new version is its reluctance to use nouns to translate nouns. We’ve already seen this in the opening sentence of chapter four: Ausgangspunkt gets eliminated in favour of ‘begins’. We repeatedly encounter verbal formulations being used where the original has substantives. An example: in the first paragraph of chapter four, §3 (chapter six in previous English versions), Marx describes labour-power as the commodity ‘deren wirklicher Verbrauch also selbst Vergegenständlichung von Arbeit wäre, daher Werthschöpfung’. Four nouns in the original. Fowkes gives us ‘whose actual consumption is therefore itself an objectification of labour, hence a creation of value’. The new translation has the following: ‘When this commodity is actually consumed, labor would be objectified, and thus value would be created’ (141); ‘this commodity’ just expands the relative pronoun deren, leaving just two nouns in place of Marx’s four. I find the result unsatisfactorily blurry; we seem to lose Marx’s focus, as conveyed by his use of substantives.

A further and more minor stylistic point. In an attempt to make Marx sound more conversational, and contemporary, the translator liberally sprinkles possessive apostrophes around. The title of volume one itself becomes ‘Capital’s Process of Production’ (9), for the German ‘Der Produktionsprozess des Kapitals’. But the results just seem too colloquial – not at all wissenschaftlich – and at times quite clumsy. (Similarly with the other contractions: ‘isn’t’, ‘aren’t’, ‘weren’t’, etc.)

I really should stop, but instances of ungainly and defective treatment of Marx’s text keep on coming. Another striking example: at the end of §1 of chapter eight on ‘The Working Day’ (chapter ten in previous English editions), Marx tells us that ‘Zwischen gleichen Rechten entscheidet die Gewalt’. Short and snappy! Punchy, even. Fowkes gives us: ‘Between equal rights, force decides’ (here, as so often, just copying Moore and Aveling’s 1887 version, merely adding the comma). The new translation has the following: ‘In such situations, whoever has more power will decide which right is enforced.’ (207) This seems remarkably feeble and flabby, as well as being actively misleading (there is nothing to support ‘which right is enforced’, as if it is simply a matter of one over the other). And the rhythm of Marx’s prose in this paragraph is ruined. To make matters worse, in the previous sentence, Marx’s Antinomie is given as ‘theoretical impasse’!

There is one significant place where the translation clearly deviates from the professed intention to be strictly following the 1872 German original. At the beginning of chapter four, just after the ‘worst of architects/best of bees’ passage, we read Marx saying that the worker can enjoy the labour process ‘as the free play of his physical and mental powers’ to different degrees (154). But the German simply says ‘als Spiel seiner eignen körperlichen und geistigen Kräfte’ – there’s no ‘free’ there. Notwithstanding this, the editors get rather excited about this idea of ‘free play’, providing an endnote citing Kant and Schiller (816). But it is just not warranted by the German text. Now, the editors might think they are justified here given Marx’s subsequent use of the phrase ‘freien Spiel der physischen und geistigen Kräfte’ (at the beginning of §5 of chapter eight on ‘The Working Day’, here 235). But this is in the context of his discussion of ‘disposable [namely, ‘free’] time’, not the labour process. The 1872 text is therefore telling us that work can be satisfying and enjoyable, but only to an extent (the ‘play’ of one’s faculties is always to some degree constrained, thus cannot, even optimally, be ‘free’); whereas the activities we undertake outside work do allow for the ‘free play’ of our powers. This would then be consistent with the famous ‘realm of freedom’ passage from the end of Capital volume 3. (I should add that chapter four in the 1872-75 French version does have ‘libre jeu’; Fowkes gives ‘free play’ here.)

So far I have been dealing with the translation, but the book contains much else besides: 86 pages of introductory material and 147 pages of end material. Let us address the latter first. There is an interesting discussion by William Clare Roberts of the 1872-75 French version, plus an appendix further dealing with some of the changes in that edition. There is also an appendix providing a comparative table of contents for the 1867, 1872, 1872-75 and 1887 versions (the latter being the basis for Fowkes). This is helpful as Marx changed the division of the text into parts and chapters in both the second German edition (1872) and the French translation (1872-75). The new translation follows the 1872 arrangement, whereas the English versions by Moore and Aveling (1887) and Fowkes (1976) follow the French, and so fall out of sync with the German editions from chapter four onwards (as indicated above). However, the table of contents provided here incorrectly lays out the concordance of the chapters which make up Parts Two and Three in the 1872 edition (732), that is, fails to show that what is chapter five in 1872 becomes chapter seven in 1872-75, 1887 and 1976, and similarly for the next four chapters. The endnotes are generally helpful, relying as they do on MEGA scholarship (lxxiv). There are interesting discussions of points of translation. But there are also mistakes. One endnote tell us that the Levellers ‘advocated for power transfer to the House of Lords’ (807)! More worryingly, the endnotes are regularly both prolix and unreliable when it comes to philosophical matters. An astonishing moment comes in the endnote appended to the passage in chapter nine where Marx refers to ‘the law Hegel discovered in his Logic’, namely that ‘at a certain point, purely quantitative changes become qualitative distinctions’ (278). The editors in their endnote then suppose that this means that the ‘capital system perverts ontology’ (826). But this law is ‘ontology’, to use their term, realized, so Marx tells us, in the ‘natural sciences’! And this failure to understand what Marx (and Hegel) mean is manifested on many other occasions.

Just to give one further example. In the ‘Editor’s Introduction’, we read the following remarkable statement:

Early in his writing life, Marx identified in the labor process an effect he called “alienation,” insofar as in capitalistic labor, a product made by one person would be taken away and used to benefit someone else, not the worker but an owner who did not participate directly in making the product. Later in Capital, Marx identifies something else in this process, a new critical name for the process itself, an abstraction that he makes for critical purposes, looking at the concrete labor process, which he calls “reification.” With this word he names the way that, in the capital system, processes get rolled up and congealed in things. (lv, underlining added for emphasis)

Let us pass over the inept account of alienation. The term ‘reification’ is standardly used as the English equivalent of Verdinglichung. We are then told that Marx uses this term in Capital. But Verdinglichung – in any form – does not appear in the text at all! Nor does the translation of Capital which follows feature the term ‘reification’ in any form. The closest in the original is the one use of Versachlichung which I discussed above and which does not fit with what is described here as ‘reification’. Now, an interesting debate can be had about the extent to which the Lukácsian concept of Verdinglichung is applicable to Capital. But to assert that it is in effect one of the key categories we already find in the text is completely misleading. And remember, this isn’t just some random internet commentator; this is one of the two editors of the very version of Capital we are about to read, presumably at least partly responsible for the fifty pages of explanatory endnotes to the text. To put it mildly, this does not inspire confidence.

So where are we? As emphasized at the outset, this new translation does have many commendable features. But it also has very serious defects, both as a translation of and as an edition of Capital. As a result, it cannot be taken to replace Fowkes. But there is, I believe, due to be a third contender, a translation of Thomas Kuczynski’s 2017 Neue Textausgabe edition coming out at some stage in the Historical Materialism Book Series. This, one would hope, will be much more successful than the volume under review here. But Kuczynski’s edition is highly revisionary – he outdoes Engels in tweaking Marx’s text in accordance with what he takes to be the author’s intentions. Two examples: (i) as mentioned at the beginning of this review, Kuczynski incorporates (that is, translates into German) the French une oeuvre de l’histoire in chapter one (thereby bringing his edition into conformity with both Moore/Aveling and Fowkes); (ii) he deletes the paragraph a couple of pages later on in chapter one where Marx provides his ‘geometrical’ analogy for the ‘common element’ shared by all commodities, on the basis that Marx crossed this out in his own copy of the 1872 edition. All these changes are detailed in Kuczynski’s massive Historisch-kritischer Apparat volume (944 pages, as opposed to a mere 800 pages for Das Kapital itself). This apparatus volume is only available in electronic form, but is really essential in order to be able to use this version of Das Kapital properly. So will the Historical Materialism translation include Kuczynski’s apparatus? We wait to find out…

Meade McCloughan is on the organizing group of the Marx and Philosophy Society and teaches philosophy for the Oxford University Department of Continuing Education.

Spread the word