This article appears in the June 2023 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.

The Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition’s downtown office is in a space of the kind that architects designed for brick buildings a century ago, with large windows that flood a room with natural light even on a cloudy Saturday in April. A small multiracial group of residents met there to refocus their city on a new version of a transit plan long weighed down by inequities older than the room they sat in. A huge map of the Baltimore region hung to one side of the room. One red line snaked across its center along an east-west axis.

It represented the original route of the Red Line, a proposed light-rail connection. Over the course of the day, older battle-energized veterans and young people new to the cause dove into how the line would improve local connection—not just in mobility, but also in civic engagement and civic life. They strategized about what to say to persuade people to sign a new ballot petition to create a regional transportation authority for the Baltimore area. No one said much about the map itself. They didn’t have to.

The cancellation of the Red Line is a transgression deeply etched in the collective memory of Baltimore. Few places are as haunted as this city is by the egregiousness of its systemic racism in public transit. Generations of African American Baltimoreans have been consigned to lifetimes of substandard travel by the failure of white politicians, and business and civic leaders, to connect up their neighborhoods with the city’s major job hubs situated along that axis.

Many Black residents had been eager to see the link built to help revive the beleaguered neighborhoods shattered by the uprising that erupted in 2015 after Freddie Gray died from the injuries he suffered in the back of a police van. Poised to receive $900 million from the federal government to build the nearly $3 billion light-rail link, then-Republican Gov. Larry Hogan shook Baltimore again just weeks after the unrest by rejecting the Red Line funding agreement for the 14-mile-long route.

Several years earlier, rejecting federal transit funds had become something of a hobby for Republican governors. Then-Gov. Rick Scott of Florida pulled the plug on a Tampa–Orlando high-speed rail line; Scott Walker of Wisconsin sent back funds for a high-speed train between Madison and Milwaukee; and Chris Christie of New Jersey rejected money for a rail tunnel.

For his part, Hogan termed almost a billion for Baltimore a “wasteful boondoggle,” but he did accept almost $1 billion for the Purple Line, a light-rail line running through two thriving Maryland suburbs bordering Washington, predominantly white Montgomery County and predominantly Black Prince George’s County. The proposed Baltimore rail line, by contrast, had been designed to connect low- and moderate-income Black neighborhoods with Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center at its eastern end, and with the headquarters for Social Security and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid just over the western city line in Woodlawn. The line, however, also edged too close for comfort to adjacent white communities. State funds that would have gone to the Red Line went straight to road projects in rural white areas. The city did, however, get millions for a new youth detention center. Baltimore has seethed about those body blows ever since.

Baltimore has uniquely bad transit for a city its size; it’s a model of inconvenience.

Linking communities along an east-west axis with faster options than buses is something so basic that many American cities on the East Coast had figured it out by mid-century. Baltimore, the largest city in one of richest states in the country, never did. Nearly 25 years into the 21st century, a viable east-west connection is still just a red line on a map.

Enter the state’s first Black governor, Wes Moore, who took office in January. The charismatic social entrepreneur who made his mark with nonprofit work on poverty and education took down a 2022 primary slate of Democratic politicos, including former DNC chair Tom Perez. He pulverized his far-right Republican opponent in the general election.

After six months in office, Moore has already sketched out his transit equity legacy by pledging to finally build the Red Line—providing access to opportunity to people long denied the tools to improve their lives. At that Saturday meeting of Red Line advocates, Samuel Jordan, the president of the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition (BTEC), called on Moore to pick up the pace. The day before the meeting, Jordan told the Prospect, “We need a clear demarcation between the Hogan era and the Wes Moore era, particularly with respect to transportation investments.” At the BTEC gathering, Jordan had choice words for the Moore administration’s public-facing work. “This governor hasn’t yet taken any concrete steps to finish the Red Line, and no one has taken any real concrete steps yet to engage with communities along that corridor in planning for development in the future,” he said.

BALTIMORE, WITH A POPULATION OF ABOUT 580,000, has uniquely bad transit for a city of its size. Its system, run by the Maryland Transit Administration, a state agency, is a model of inconvenience. Riders endure one or more long bus commutes (with traffic, 90 minutes or more each way is not unusual), often enough in slow-moving traffic, to get across town. Jason Haeseler, a math teacher at Patterson High School in East Baltimore, has a shorter, one-seat bus ride from his home in the same neighborhood, but he gets an earful from his students, who commute from all over Baltimore to attend one of the most diverse schools in the city—some of them need three bus transfers to get there.

The Northeast Corridor’s other major cities—Washington, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston—all have had extensive networks of bus and rail lines for decades. Since the 1980s, Baltimore has had just two north-south running rail lines: the Baltimore Metro SubwayLink, a single solitary line that seems to be largely unknown to the outside world (one Redditor recently dropped into the Baltimore subreddit to ask about “the mysterious subway”) and the Baltimore Light RailLink, which runs from Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport through downtown and on to suburban Hunt Valley, and which has a reputation for subpar service. “One big challenge is there is not a defined culture of transit in the city,” said Derek Moore, a Baltimore resident (no relation to the governor) who attended the BTEC meeting.

During the pandemic, bus lines were targeted for cuts, even though the light rail shed more of its mostly white riders than the buses that moved mostly Black essential workers. Today, Baltimore’s bus network has recovered to about 85 percent of its pre-pandemic ridership while the rail links struggle. The transit coalition’s campaign to set up a regional transit authority in tandem with a new Red Line argues that an independent authority would do a better job than the MTA has of aligning the metro region’s various interests.

Blame much of Charm City’s bad transit on the interstate highway mania of the 1950s, which had very different outcomes in two cities than less than 50 miles apart. Both Baltimore and Washington were targets of aggressive highway campaigns, but only one walked away with the crown jewel of a world-class subway system. In Washington, another multiracial coalition beat back the factions that wanted to spin spiderwebs of highways across the capital. The victory positioned the city by the 1970s to use the more than $1 billion that would have gone to the highways to build Metrorail instead.

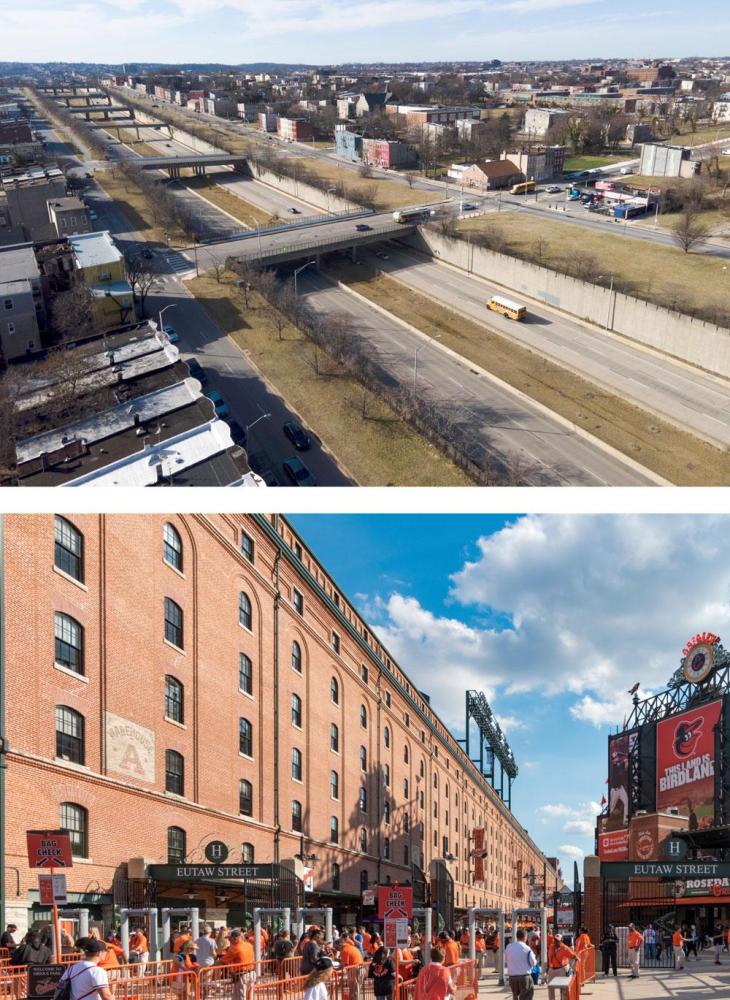

Above: The “highway to nowhere,” which cut through West Baltimore; Below: Camden Yards, which has light-rail and subway access Julio Cortez/AP Photo

Some of Baltimore’s problems can be traced back to the 1940s, when city leaders called in Robert Moses, New York’s legendary builder of highways. Moses brought with him his distinct contribution to urban restructuring: building expressways that pushed low-income people, and especially African Americans, out of certain areas he wanted repurposed. In Stop the Road: Stories From the Trenches of Baltimore’s Road Wars, Evans Paull, a retired Baltimore city planner, documents how a “Franklin Expressway” plan, ultimately shelved, would have forced about 18,000 people out of their homes. “Some of the slum areas through which the Franklin Expressway passes are a disgrace to the community, and the more of them that are wiped out,’” Moses argued, “the healthier Baltimore will be in the long run.” Local business groups of the period, like the Association of Commerce, endorsed the idea.

By the late 1960s, however, Baltimore transit planners had envisioned a six-line Baltimore Region Rapid Transit System, somewhat similar to Washington’s. But Baltimore politicians, planners, and business leaders had exhausted themselves and their treasury with highway schemes that the city ultimately could not pay for. They had little interest in repurposing highway dollars to subways. They also had let the streets crumble, leaving furious residents demanding repairs—not rail.

William Donald Schaefer, the powerful, pro-highway mayor of Baltimore who later became Maryland’s governor, decided to save face by building a truncated span of a larger interstate highway project that was later abandoned and came to be known as the “highway to nowhere.” It did succeed, however, in ripping out West Baltimore homes and displacing hundreds of families.

Schaefer did support public transit when it came to two of his pet legacy development projects: the Inner Harbor, with a then state-of-the-art aquarium and indoor mall and food courts, which opened in 1983, and Camden Yards, the Baltimore Orioles’ baseball stadium, which opened in 1992. He belatedly had realized that the downtown area couldn’t handle the throngs of fun-and-games-seeking white suburban drivers drawn to those attractions.

Unlike their counterparts in Washington, there was little support among white Baltimoreans for expensive and complex rail projects that they viewed as solely benefiting Black people. While the Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland eds and meds centers are on or near those rail lines (and bus lines, of course), the government centers remain bus-dependent destinations.

Baltimore was the birthplace of redlining in the early 1900s, and similar racist perspectives have shaped the city’s and the state’s policies in transportation, education, and policing. Brian O’Malley, president of the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance, explains that “if you look at maps of historic redlining, if you look at a lot of the indicators where people live, by race, by income, and where people don’t have a car for every working adult in the house, the lack of rapid transit matches up with some of those other indicators of historic institutional racism and lack of resources.”

AMERICAN POLITICIANS OFTEN SUCCUMB TO THE IMPULSE to come up with a manifesto that ticks all the boxes about Big Issues of the Day. Moore authored five books (four nonfiction and one young-adult novel) before he was elected governor. After the sudden death of his father when he was a toddler, Moore moved with his mother and sisters from Takoma Park, Maryland, to live with his maternal grandparents in New York. Equity and access to opportunity figure in his public comment on transportation, and his published works provide snippets of Moore’s experiences with New York’s intense public-transit culture before he returned to the Maryland area as a teenager.

Moore learned to navigate the ebb and flow of the subways between his home in the South Bronx and the rest of the city. In Discovering Wes Moore (the young-adult version of his autobiographical memoir), he observes, “On the Number 2 train home, we were crushed in a crowd of executives, construction workers, accountants, and maids. Hands of all colors clung to the metal pole in the middle of the subway car. Justin broke down his strategy for securing a seat. ‘Just stand next to the white people. They’ll get off by a Hundred and Tenth Street. I swear you’ll see. Give it six more stops.’ I grinned at him, then nodded in awe as his prediction came true. All the suits emptied the train by the time we hit 110th Street, the last wealthy stop in Manhattan … A subway car full of blacks and Latinos would continue the ride up to Harlem and the Bronx.”

By the time he had settled in Baltimore, Moore had a more sobering impression of transit’s impact on a city. In 2020, one year before he announced he’d run for governor, he wrote Five Days: The Fiery Reckoning of an American City with The New York Times’ Erica L. Green, a former Baltimore Sun reporter who’d covered the 2015 uprising. The book profiles eight Baltimoreans’ experiences during the Freddie Gray uprising. One of them, Major Marc Partee, a Baltimore police officer, had to come to grips with the Baltimore Police Department’s decision to shut down the Mondawmin Mall, which Moore describes as “a true transportation hub in a city not known for its transportation assets,” where a number of bus lines and the metro meet. Moore described that decision as one of the period’s “big unanswered questions.” Clearly, however, that one order epitomized the authorities’ lack of consideration for Black Baltimoreans’ basic needs, stranding already angry young people and exacerbating the conditions that fueled more unrest in the week after Freddie Gray’s funeral.

SCUTTLING AN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT IS EASY. Resurrecting it takes time and megabucks. Rather than starting from square one, the Moore administration wants to salvage some part of the more than two decades’ worth of the original Red Line work for its new federal application.

Moore has certain advantages. His selection of Paul Wiedefeld, the former general manager of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, as Maryland’s transportation secretary raised some questions thanks to Wiedefeld’s sometimes dicey six-year tenure at an agency in the throes of its own midlife crisis. But the Baltimore native also had run Maryland’s transit and aviation agencies. He was the transit administrator who signed the original 2008 Red Line community compact, which included an outline of which experiences from similarly situated cities could be applied to the Red Line. The Wiedefeld pick signaled that the new governor wanted an adviser already well versed in the terrain.

The Red Line proposal, with a new estimated $3.4 billion price tag, has lined up key supporters in its bid for federal dollars. Maryland Sens. Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen gave the Red Line a boost by inserting a provision in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that allows states like Maryland to get back into one of the federal government’s most complex hyper-competitive grant processes by allowing previously approved projects that have been on pause to reapply.

Wes Moore, Maryland’s first Black governor, has made salvaging the Red Line a priority. Susan Walsh/AP Photo

But a number of things have to fall into place for the Red Line to win new capital improvement grant monies from the Department of Transportation. For starters, Maryland has to come up with some coin itself. With Democratic supermajorities in both chambers, Moore had proposed tapping into the state’s rainy day fund for $500 million to be divvied up between the Red Line and other transportation priorities. But the projected budget surplus fell short of expectations, and state lawmakers prioritized education, cutting Moore’s transit request to $100 million with a possibility for an additional $100 million. That covers just a fraction of what the line requires. In 2015, the state had lined up about $1.7 billion, plus funds from localities, Maryland’s Transportation Trust Fund, and a possible public-private partnership.

State officials also have to figure out what they can salvage on the environmental front. Does the environmental impact statement that must accompany a new application need to be completely redone? Or can an earlier one at least be amended to indicate how the project meshes with new development and other changes along the route?

Not surprisingly, Wiedefeld is upbeat. “Every project I’ve dealt with, either at the airport, Metro, or the MTA, there’s never been a clear path,” he told the Prospect. Can Maryland do the project without federal dollars? “My preference obviously would be to get as many federal dollars as I can.”

The hope is that a legislatively mandated east-west corridor study which just happened to appear in the waning months before Hogan left office in 2022 can help backstop the state’s application without requiring a brand-new environmental impact statement. The study examined how to improve transit access for the Central Maryland region—Baltimore City and four adjacent counties. It contained assessments of how the project would impact the environment and a menu of feasible alternatives, which are required by National Environmental Policy Act processes for transit projects.

The corridor study lists seven east-west alternatives, which include light-rail and bus rapid transit options. (One is a subway, which is almost certain to be out of the running due to construction costs and disruptions.) One of the light-rail proposals (known as “Alternative 6”) mirrors the original Red Line route, according to Klaus Philipsen, who worked on the design team for the Red Line from 2002 to 2015. “This is the thing in transportation: Transit doesn’t change all that often and rapidly,” he said. Asked if Alternative 6 was going to be the choice, Wiedefeld wasn’t going there. “I think it’s too early to get that far,” he says.

Equity concerns could also figure into the state’s calculus. In 2015, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund filed a civil rights complaint with the Department of Transportation, alleging that Gov. Hogan had violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by canceling the Red Line and diverting the funds to rural white areas. When Donald Trump came into office, the Department of Transportation closed the investigation.

NIMBYs ready and willing to muck things up pose another potential set of challenges—wealthier harborside neighborhoods that were hotbeds of opposition the last time around may still frown on an aboveground line running past their homes. And some suburbanites still fear rail as a gateway to the denser “urban” communities that threaten their “lovely suburbia,” as one local official described another light-rail proposal. The threat of crime by pillaging “elements” (read: African Americans) usually factors in at some point, too. Ludicrous as those fears may be, suburban apprehension about “loot rail” (a claim that hung over the original Red Line, never backed by any data) could deter the project.

For now, the memories of what might have been are enough to power the Red Line.

Nor is there a uniform guarantee of support from Black Baltimore neighborhoods, especially the ones convulsed by the construction of the highway to nowhere. Not only were residents forced from their homes that were demolished, but others were forced to give up their homes that didn’t fall to the wrecking ball after much of the original project was abandoned and their homes left standing. That left many community members suspicious of “improvements” or “new investments,” which they have often viewed as Trojan horses for new displacements.

Moore will have to dig deep into his inner visionary and then some, given the long haul that’s ahead. “There’s still anger about the cancellation of the Red Line, which may help to mobilize the city more actively than it would be otherwise,” says Matthew Crenson, an emeritus professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University.

The questions keep coming about a next-generation Red Line and all its moving parts, from design and engineering to possible procurements and permitting to getting community input and support—and they all need answers before the bulldozers move in. The first time around, two years passed from the Department of Transportation’s final environmental impact statement approval to a federal funding commitment. The initial estimate for construction? Six years.

“It took about 15 years of planning and lobbying to get to the point where they got plans approved, money in place, so Moore is going to have to go through building that kind of support again,” says Sheryll Cashin, a professor of law, civil rights, and social justice at Georgetown Law. “There was a huge empathy gap between Hogan and the Black citizens of Baltimore,” she adds. “[The Moore administration] should be able to get it done. If they can’t, that’s quite a statement.”

But while not overselling expectations may have its merits, failing to fill that messaging void with concrete information about next steps leaves Red Line supporters anxious. Pushing any backdoor, less expensive options, such as bus rapid transit, won’t fly either. “I want to make sure that we’re sticking with rail, which the original Red Line was, because rail is better at attracting that economic development,” says Delegate Sheila Ruth, who spoke to the BTEC group at their April meeting, and represents a western section of Baltimore County in the state legislature.

Moore has to hack through some brutal terrain. He appears to have supportive partners in Washington, at least as long as the Biden administration runs it. But he needs billions in rock-solid funding, and only a portion of that is going to come from the feds. He’s likely to need two terms in office to make any serious progress. And on the cusp of a presidential election, there’s always the possibility of an increase in the numbers of transit-resistant Republican congressmembers wanting to meddle in other states’ affairs.

Providing estimates of project milestones and dates is not unreasonable. But, above all, Moore has to keep public messaging and communications transparent and accurate to keep Baltimore’s African American communities—long since suspicious of political pledge-making—on board. Otherwise, he runs the risk of defeating his own purpose by letting a “this is never going to happen, so why should I care?” mindset creep in.

For now, the memories of what might have been are enough to power the Red Line forward. “The same people are working the same jobs, waiting for the same buses they were waiting for—what, seven years ago? Eight years ago? That rail line could have been built by now. Those people are still around and remember,” says Haeseler, the high school teacher. “The faster that Wes Moore can move, the better.”

Read the original article at Prospect.org.

Used with the permission. © The American Prospect, Prospect.org, 2023. All rights reserved.

Prospect senior editor and award-winning journalist Gabrielle Gurley writes and edits work on states and cities, transportation and infrastructure, civil rights, and climate. Follow @gurleygg

TAP depends on your support

We’ve said it before: The greatest threat to democracy from the media isn’t disinformation, it’s the paywall. When you support The American Prospect, you’re supporting fellow readers who aren’t able to give, and countering the class system for information. Please, become a member, or make a one-time donation, today. Thank you!

Spread the word