As the recent defeat of progressive Philadelphia mayoral candidate Helen Gym vividly demonstrated, progressives — like Democrats broadly — continue to struggle with working-class voters. Progressives hardly ever run outside of deep-blue districts, where they typically depend on middle-class constituencies for victory. And, with notable recent exceptions like John Fetterman in 2022, they often fail to compete effectively in heavily working-class areas when they do run.

Since 2020, however, at least some progressives have begun to recognize the scale of the problem, dedicating more attention to bread-and-butter economic issues they hope will resonate with working-class voters and reengaging with the labor movement.

The Center for Working-Class Politics (CWCP) sees its work as part of this larger project. We aim to provide research that will help progressives expand their appeal among working-class voters, in the hope of achieving our shared political goals.

In November 2021, together with Jacobin and YouGov, the CWCP published findings from our first original survey experiment, designed to better understand which kinds of progressive candidates, messages, and policies are most effective in appealing to working-class voters.

Among other things, the survey found that voters without college degrees are strongly attracted to candidates who focus on bread-and-butter issues, use economic populist language, and promote a bold progressive policy agenda. Our findings suggested that working-class voters lost to Donald Trump could be won back by following the model set by the populist campaigns of Bernie Sanders, John Fetterman, Matt Cartwright, Marie Gluesenkamp Pérez, and others.

Yet our initial study left many questions unanswered and posed many new ones. Which elements of economic populism are most critical for persuading working-class voters? Would economic populist candidates still prove effective in the face of opposition messaging and against Republican populist challengers? How do voter preferences vary across classes and within the working class? Can populist economic messaging rally support from working-class voters across the partisan divide?

To address these questions, we designed a new survey experiment in which we presented seven pairs of hypothetical candidates to a representative group of 1,650 voters. We assessed a vast range of candidate types (23,100 distinct candidate profiles in total) to better understand which candidates perform best overall and among different groups of voters.

Our aim was to test which elements of economic populism are most effective in persuading working-class voters, how the effects of economic populist messaging change in the face of opposition messaging, and how these effects vary both across classes and within the working class.

Overall, we find that progressives can make inroads with working-class voters if they run campaigns that convey a credible commitment to the interests of working people. This means running more working-class candidates, running jobs-focused campaigns, and picking a fight with political and economic elites on behalf of working Americans.

The key takeaways of our survey, listed briefly below and discussed in greater detail in the full report and in this summary, can inform future progressive campaigns.

Some of Our Key Takeaways

Running on a jobs platform, including a federal jobs guarantee, can help progressive candidates. Virtually all voter groups prefer candidates who run on a jobs platform. Remarkably, respondents’ positive views toward candidates running on a jobs guarantee were consistent across Democrats, independents, and even Republicans. Candidates who ran on a jobs guarantee were also popular with black respondents, swing voters, low-propensity voters, respondents without a college degree, and rural respondents. Across the thirty-six different combinations of candidate rhetoric and policy positions we surveyed, the single most popular combination was economic populist rhetoric and a jobs guarantee.

Populist “us-versus-them” rhetoric appeals to working-class voters, regardless of partisan affiliation. Working-class Democrats, independents, Republicans, women, and rural respondents all prefer candidates who use populist language: that is, sound bites that name economic or political elites as a major cause of the country’s problems and call on working Americans to oppose them.

Populist “us-versus-them” rhetoric appeals to working-class voters, regardless of partisan affiliation. Working-class Democrats, independents, Republicans, women, and rural respondents all prefer candidates who use populist language: that is, sound bites that name economic or political elites as a major cause of the country’s problems and call on working Americans to oppose them.

Running more non-elite, working-class candidates can help progressives attract more working-class voters. Blue- and pink-collar Democratic candidates are more popular than professional and/or upper-class candidates, particularly among working-class Democrats and Republicans. Non-elite, working-class candidates are also viewed favorably by women, Latinos, political independents, urban and rural respondents, low-propensity voters, non-college-educated respondents, and swing voters.

Candidates who use class-based populist messaging are particularly popular with the blue-collar workers Democrats need to win in many “purple” states. Manual workers, a group that gave majority support to Trump in 2020, favor economic populist candidates more strongly than any other occupational group. Low-propensity voters also have a clear preference for these candidates.

Right-wing opposition messages do not undermine the effectiveness of jobs-focused campaigns, economic populist language, or the appeal of non-elite, working-class candidates. In fact, our study suggests that candidates running on a progressive jobs policy may actually be more effective in the face of right-wing opposition messaging.

Rural voters across the political spectrum support key elements of left-wing populism. While rural Democrats and independents support pink-collar candidates and rural Republicans support small-business-owner candidates, they all share a dislike for upper-class candidates, prefer candidates running on a progressive jobs guarantee, and respond favorably to populist messaging.

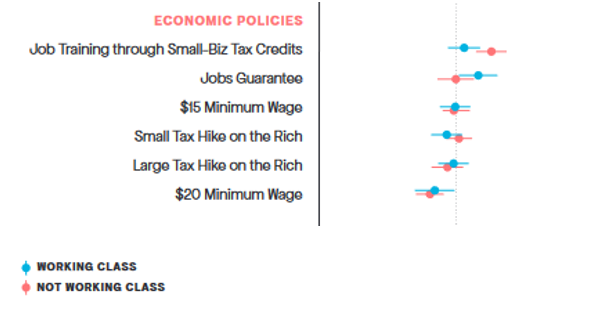

Class matters. Working-class voters respond differently to Democratic candidates, messages, and policies than other voters. As defined by occupational group, working-class respondents across the political spectrum have a particularly strong preference for non-elite, working-class candidates; managers and professionals do not. Working-class respondents also find economic populist language and a federal jobs guarantee more appealing than other messages and policies; non-working-class respondents do not.

These class-based preferences persist within racial and ethnic groups: black working-class respondents, for instance, enthusiastically favor economic populist rhetoric, while black managers and professionals are averse to it. Working-class white respondents strongly favor non-elite candidates; their middle- and upper-class counterparts do not.

Progressives running on the Democratic ballot line should consider distancing themselves from the Democratic Party establishment. Regardless of class, gender, or race, we found that respondents tend to favor Democratic candidates who call out the Democratic Party for failing working-class Americans.

You can read the full report here.

Spread the word