MADRID — If you thought the political drama in Spain would conclude with Sunday’s national election, think again.

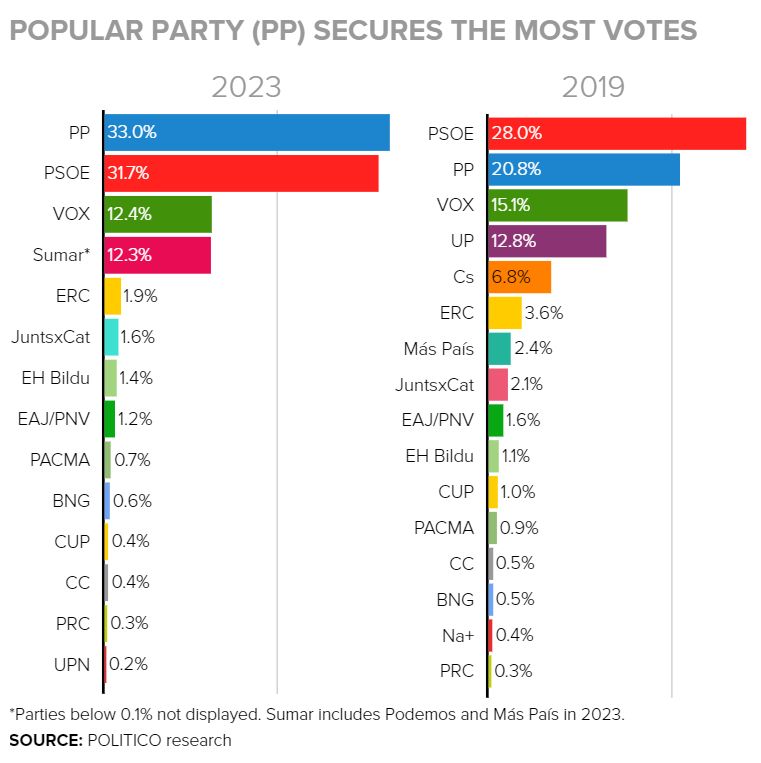

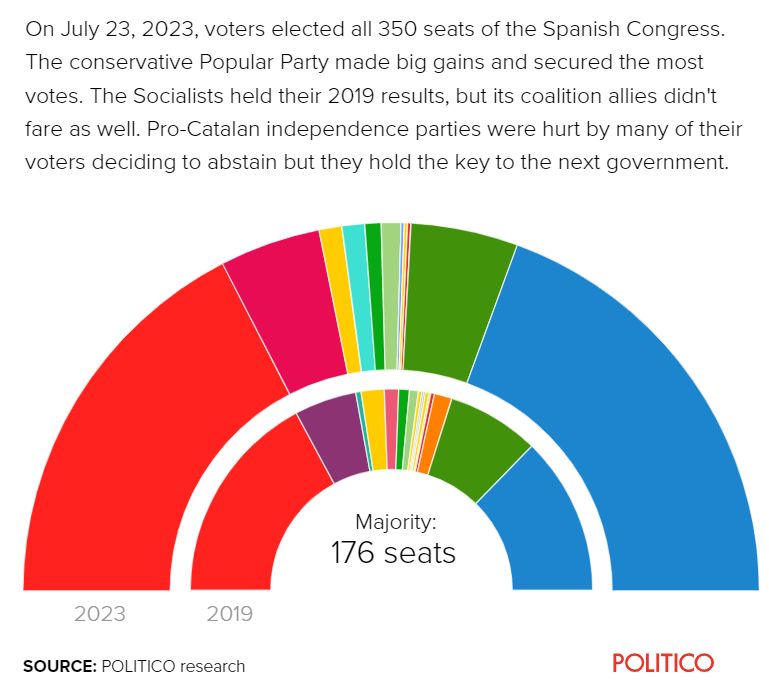

The inconclusive national vote resulted in a split parliament with no clear governing majority. The center-right Popular Party secured the most votes, but it doesn’t have nearly enough seats to form a government on its own or even with the far-right Vox party, its preferred coalition partner.

On Sunday night, conservative leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo said he would attempt to form a minority government and demanded “no one be tempted to blockade Spain.”

Feijóo argued the country has always been governed by the leader who secures the most votes, and insisted the future government needed to be “in accordance with the electoral victory.”

But in parliamentary democracies like Spain, the head of government isn’t necessarily the person who wins the most votes in the election, but rather the one who can secure the support of the greatest share of MPs — and right now Feijóo does not have the backing needed to make his candidacy for prime minister viable.

Socialist leader and current Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, meanwhile, has a possible — though extremely complex — route to victory.

Sánchez’s Socialists and his preferred partners, Yolanda Díaz’s left-wing Sumar coalition, control 153 seats in parliament. Although the left-wing allies are unlikely to secure the backing of the 176 MPs needed for Sánchez to be confirmed as prime minister the first time the new parliament votes on the matter, they could make a bid during the second round of voting, in which the candidate to head the new government must receive more yeas than nays.

But Sánchez will have to move quickly to prove his bid to stay in power is realistic.

A break, then a visit with the king

After a grueling campaign characterized by ugly, personal attacks, everybody needs a breather. So it’s just as well that Spain’s parliament is only due to be reconvened on August 17, when MPs will be sworn in.

But once parliament is back in session, Sánchez will have to clear an initial royal hurdle.

In the days following the start of the new parliamentary session, Spain’s King Felipe VI will summon the leaders of the political groups for consultations at Zarzuela Palace and quiz them on who they think has the most support to form a government.

Feijóo will press his case and insist that, as the leader of the party that received the most votes, he should be named the candidate for the next prime minister.

While thus far Spain’s prime minister has indeed always been the politician who garnered the most votes in the election, Pablo Simón, a political scientist at Madrid’s Carlos III university, said the king’s responsibility would be to entrust the formation of a new government to whichever leader can show they have the backing to overcome the key investiture votes in the Spanish parliament.

“The king is cautious and will follow the rules set out in the constitution,” Simón said. “In other words, he’ll order a government from the person whose candidacy is viable.”

So Sánchez will need to ensure that when he shows up at Zarzuela Palace, he does so with a convincing list of supporters, preferably with several other party leaders openly indicating their willingness to back his candidacy.

Epic horse-trading

If Sánchez succeeds and the king names him the candidate to be Spain’s next prime minister, the incumbent will have several weeks to negotiate with potential backers.

In 2019, Sánchez managed to form Spain’s first left-wing coalition government by striking deals with regional parties that supported his candidacy in parliament in exchange for concessions in the form of infrastructure like new railways or hospitals.

But in these high-stakes elections, voters opted to back larger parties, and smaller ones like the Teruel Existe citizens movement — which was key to Sánchez’s victory in 2019 — lost their seats in parliament.

This time around, Sánchez will need Basque and Catalan separatist groups like EH Bildu and the Republican Left of Catalonia to vote in favor of his candidacy. He’ll also need to convince Junts — the party founded by former Catalan President Carles Puigdemont — to not vote against him.

Although Sánchez’s left-wing coalition government has sought to mend ties and take a softer approach with Catalan separatists during the past four years, relations are by no means ideal.

Puigdemont, who fled Spain in the immediate aftermath of the 2017 Catalan independence referendum, remains in self-imposed exile in Belgium. The politician, who is currently a member of the European Parliament, recently had his legal immunity stripped by a top EU court, paving the way for his extradition to Spain.

On Sunday, Junts candidate Míriam Nogueras told the press her party had “understood the result” and would “take advantage of the opportunity.”

But she signaled negotiations with the Socialists would not be easy, and that a positive outcome was by no means certain.

“This is a possibility for change, to recover unity,” she said. “But we will not make Pedro Sánchez president in exchange for nothing.”

What next for Sánchez and Feijóo

If Sánchez is asked to form a government but fails to win the required support in parliament, Spain is likely to face a new election.

Feijóo could press the king to allow him to try to form a government if Sánchez’s bid fails. But his backing in the parliament is unlikely to be altered dramatically in the next few months, meaning he probably wouldn’t have the necessary support to succeed.

Moreover, if Sánchez loses the votes in parliament, Feijóo may well decide he’s better off waiting for new elections in which he can argue that his opponent wasted everyone’s time and left Spain without an effective government for an entire season.

The Spanish constitution dictates that the king is obliged to dissolve the legislative body two months after the first failed investiture vote. Given that a new ballot must be held 54 days after the legislature concludes, if Sánchez fails to secure parliament’s support, Spaniards would go to the polls again at the end of this year or, more likely, at the beginning of 2024.

Until a new prime minister is confirmed by parliament, Sánchez will remain as head of government in a caretaker position with limited powers: No new laws can be adopted except in emergencies.

That means that, whatever happens, Sánchez is on track to remain Spain’s prime minister for the foreseeable future — but what’s next for Popular Party leader Feijóo is less clear.

When Feijóo attempted to deliver a speech to supporters Sunday night, the crowd drowned out the conservative politician by shouting the name of Madrid’s populist regional president, Isabel Díaz Ayuso.

Prior to the election Ayuso, who is wildly popular among Popular Party voters, implied her support for Feijóo’s leadership was linked to him winning this election.

Despite scoring the most votes, whether Feijóo fulfilled his mission may now be matter of opinion.

Aitor Hernández-Morales is a reporter for POLITICO and the author of our Living Cities Global Policy Lab.

Prior to joining POLITICO, Aitor covered Portuguese politics and social issues as the Lisbon-based correspondent for Spain’s El Mundo and the Cadena SER radio network, and collaborated with Spain’s El Español and Ahora Semanal, France’s Courrier International, and Canada’s CTV News. He also spent several years working in the civil infrastructure sector, and previously served on El Mundo’s International and Breaking News desks, where he covered European affairs.

Born in Pamplona, Spain, but raised in Miami, Florida, Aitor has lived in Germany, Spain, Portugal and Italy. He speaks English, Spanish and Portuguese fluently and has a working knowledge of French, German and Italian.

POLITICO is the global authority on the intersection of politics, policy, and power. It is the most robust news operation and information service in the world specializing in politics and policy, which informs the most influential audience in the world with insight, edge, and authority. Founded in 2007, POLITICO has grown to a team of 700 working across North America, more than half of whom are editorial staff.

Spread the word