After Hamas’s brutal massacre of over a thousand Israel civilians and Israel’s massive military response, peace may appear inconceivable. Certainly, few would blame those unwilling to forgive the shocking violence of days past. Yet peace does not demand forgiveness of the unforgivable—and shattering events have a way of producing unanticipated consequences.

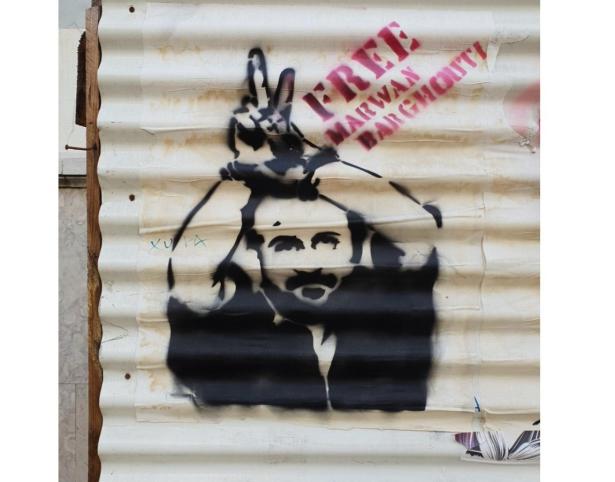

A prisoner exchange—which historical patterns suggest is likely—could, despite it all, reopen a path to peace. In 2011, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traded 1,027 Palestinian prisoners (280 of them serving life sentences) to obtain the release of a single Israeli soldier captured five years earlier. Israel now claims that Hamas holds 199 hostages. Meanwhile, an estimated 5,200 Palestinians languish in Israeli jails—and among them is one man who may hold the key to peace: Marwan Barghouti, considered by some to be Palestine’s Nelson Mandela.

Though Israeli authorities labeled Barghouti a “terrorist” after Israeli courts convicted him on five counts of murder, the idea of releasing him is far from a fringe position: Indeed, Alon Liel, formerly Israel’s most senior diplomat, has proposed just that. Deeming him “the ultimate leader of the Palestinian people,” Liel believes “he is the only one who can extricate us from the quagmire we are in.”

As early as 2008, polling data revealed that Barghouti was far more popular among Palestinians than any other possible leader, including President of the Palestinian Authority Mahmoud Abbas and Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh. But his very popularity was a problem for Prime Minister Netanyahu.

As Hebrew University professor Dmitry Shumsky has pointed out, it has long been the unannounced policy of Netanyahu to undermine the more moderate Palestinian Authority by bolstering Hamas, which shares his hatred of the two-state solution. As confirmed by a former Israeli Cabinet minister, Netanyahu actually propped up Hamas, approving the channeling of substantial funds from Qatar to the radical Islamist organization. Paradoxically, then, there has been a de facto alliance between the hard-line Netanyahu and Hamas, long irreconcilably opposed to the existence of Israel.

In this context, the popular and charismatic Barghouti has posed a unique threat to Israel and its persistent claim that it had no plausible interlocutor with whom to negotiate. The influential Israeli newspaper Haaretz captured the underlying dynamic well as far back as 2012, stating flatly in an editorial, “If Israel had wanted an agreement with the Palestinians it would have released him from prison by now. Barghouti is the most authentic leader Fatah has produced and he can lead his people to an agreement.”

The parallels between Barghouti and Mandela, while imperfect, are striking. Barghouti has spent 27 years in prison and in exile—precisely the number of years Mandela spent in a South African prison. While imprisoned, Mandela’s convictions drove him to learn Afrikaans, the language of his captors. Barghouti, in turn, has spent his time in jail becoming fluent in Hebrew. Critically, both men advocated for peaceful coexistence with—not the annihilation of—their adversaries.One should not romanticize. Neither Mandela nor Barghouti were devotees of Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent philosophy; both believed that armed resistance to oppression was sometimes justified. As early as 1953, Mandela advocated armed resistance; classified by the South African regime as a “terrorist,” he six times refused offers of release conditioned in part on his renunciation of violence. And while Barghouti rejected violence in the early years of the Oslo peace process, claiming in 1994 that “the armed struggle is no longer an option for us,” he later embraced armed struggle as he watched Israel expand settlements in the West Bank and consolidate control. But by 2012, Barghouti admitted that the turn to violence during the Second Intifada had been a grave error, and has repeatedly stated that he supports only unarmed resistance.

Crucially, both Mandela and Barghouti arrived at a hard-won recognition that, after years of relentless struggle, they would have to learn to live with their longtime enemy. Recognizing, as he put it in his eulogy of Mandela, that they must “defy hatred and … choose justice over vengeance,” Barghouti supports, in exchange for an end to the Israeli occupation that began in 1967, permanent peace between Israel and Palestine as “independent and equal neighbors.” As such, he stands in stark contrast to Hamas’s leader, Ismail Haniyeh, who steadfastly refuses to recognize Israel.

Like Mandela, Barghouti earned the respect of his people through decades of sacrifice and commitment to the cause. And despite his over two decades in prison, Barghouti remains popular among Palestinians in both Hamas-controlled Gaza and the Fatah-controlled West Bank. Indeed, a December 2022 poll by the Palestine Center for Policy and Survey Research showed that if Barghouti were to run in a presidential election, he would defeat Haniyeh in a landslide victory.

Barghouti’s release would hardly guarantee an expeditious or smooth peace agreement between the Israelis and Palestinians; entrenched animosity and the continued occupation of Palestine by more than half a million Israeli settlers spread out over 199 settlements and 220 outposts may well prove insurmountable. Excruciating concessions must be extracted from both sides, necessitating a receptivity to compromise that would no doubt arouse fierce, and possibly violent, backlash. Yet both the Israelis and the Palestinians must ultimately choose: either an endless escalation of the cycle of violence and hatred or a grudging recognition that they must find a way to live together.

Though the intensifying conflict between Hamas and Israel is a genuine tragedy, the exchange of prisoners that will likely follow the carnage presents a historic opportunity that neither side can afford to miss: Israel must free Marwan Barghouti, the only Palestinian with the authority and vision to bring peace within the ambit of possibility.

Jerome Karabel, professor of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, is the author of The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton and several other books. The recipient of many awards, he has written for The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, The Nation, the Los Angeles Times, and Le Monde Diplomatique.

Read the original article at Prospect.org. Used with the permission. © The American Prospect, Prospect.org, 2023. All rights reserved.

Click here to support the Prospect's brand of independent impact journalism.

Spread the word