Chicago-Inspired ‘Purpose’ Explores Fictionalized Iconic Black Family in Blistering Steppenwolf Production

There’s a saying from playwright Anton Chekhov that, to paraphrase, if you hang a pistol on the wall in Act I, it needs to eventually go off.

But we can create another such maxim: If you go to the Steppenwolf Theatre for a large-scale family drama, and there’s a dining room table prominently featured in the set, you can be pretty sure you’re in for one of those knee-buckling scenes of such explosive intensity that it can eventually become a giant photograph hanging from the side of a building on Halsted Street, visible for blocks, advertising the Chicago brand of kinetic acting.

Playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and a stellar cast, under the direction of Phylicia Rashad, deliver a doozy of such a dinner scene in his new play “Purpose,” now receiving its world premiere at Steppenwolf. It’s the centerpiece of a play about a Famous Black Family — in capital letters. Clearly inspired by Chicago’s Jackson family — as in Jesse and Jesse Jr. — the play is set at a transitional moment when the family must process a problematic recent past and consider the future.

When: Through May 12

Where: Steppenwolf Theatre, 1650 N. Halsted St.

Tickets: $20-$116

Info: steppenwolf.org

Running time: 2 hours and 55 minutes, with one intermission

Solomon Jasper (Harry Lennix, oozing dignity) is a larger-than-life civil rights icon and a preacher without a congregation. Other than the occasional paid speech, he’s mostly retired and has taken up beekeeping, for reasons he’ll try to explain.

His oldest son, Junior (Glenn Davis, finding so much neediness under the surface charm), was an up-and-coming politician but is now returning from a prison sentence after embezzling campaign funds. Junior’s wife Morgan (Alana Arenas, brilliantly commanding attention even when she’s silent) has been caring for their kids during her husband’s sentence, but now needs to serve her own time for related tax fraud charges.

That’s why, rather than a homecoming party for Junior, the family has decided this get-together will be considered a very late birthday celebration for Claudine (Tamara Tunie, unyielding), a deeply protective matriarch whose every sentence seems to carry in it her strong opinions without expressing them directly, although she’s capable of that, too.

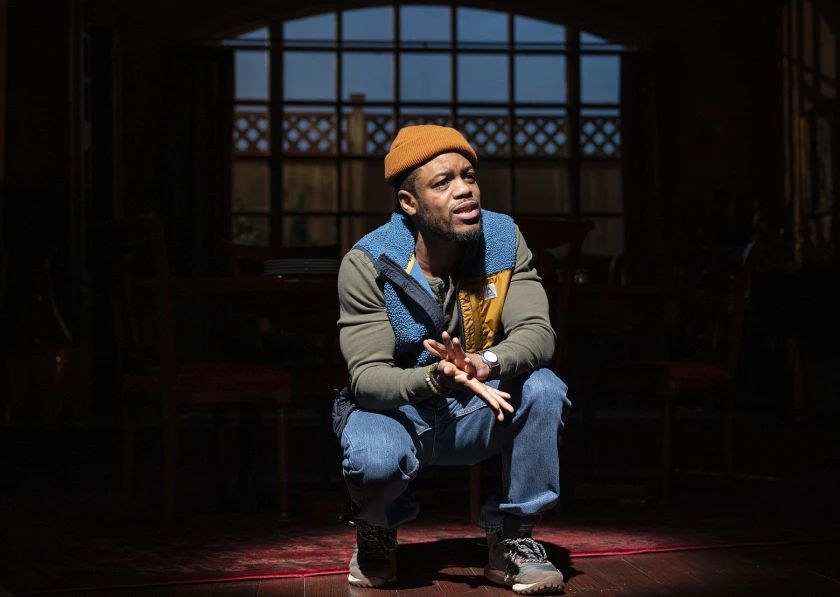

To provide a bit of distance and perspective (and pure fiction), Jacobs-Jenkins has structured this as a memory play told from the perspective of Solomon and Claudine’s younger son Nazareth (Jon Michael Hill, an emotionally generous guide).

Naz, as he’s known outside the family, has strayed from his father’s planned path by dropping out of divinity school and pursuing a career as a nature photographer. He refers to this as the “Great Disappointment,” looking at it from his father’s perspective. Then again, Naz was always the “weird son,” struggling with the social demands of being part of a famed family. His father wanted to mold him, but “the clay began to ask questions of the hand.”

Jon Michael Hill stars as Naz in in Steppenwolf Theatre Company’s world premiere of Branden Jacobs-Jenkins “Purpose,” directed by Phylicia Rashad. Michael Brosilow

And finally, there’s an outsider in the form of guest Aziza (Ayanna Bria Bakari, elevating the idea of being star-struck), Naz’s “friend.” It’s complicated you see, and every member of the family would really like to figure out what Junior refers to as their “situationship.”

The boisterous first act leads up to the dinner scene, when all the tensions and secrets get exposed, as do the raw nerves. It bears a lot of darkly comic resemblances to “Appropriate,” Jacobs-Jenkins drama about a white Southern family — now a giant hit on Broadway after it premiered in Chicago over a decade ago.

The second act, though, comes off as something very different. Jacobs-Jenkins stops piling on new revelations and instead lets the characters contemplate what we already know. Sure, there’s still some story and a Chekhovian turn, but I think Jacobs-Jenkins may have limited himself to where he could go here, having gotten so close to a real-life family. It’s also clear, though, that Jacobs-Jenkins, now nearing 40, is letting himself be looser, allowing his characters to talk, letting in essence the clay talk back to the hand.

The play’s second half may not have the same entertainment value, but the dialogue reaches for a depth that few writers even attempt. In the opening monologue of the play, Naz refers to trying to capture pictures of lakes in a way that “you could take in the entirety of it.”

It’s not hard to discern that Jacobs-Jenkins, in addition to exploring what it’s like to be part of an iconic Black family, wants to use that as a stepping stone to considerations of Even Bigger Things, like the nature of humans’ desire to have children; human differences that encompass mental illness, neuro-divergence and sexuality; the management of regret; and, perhaps above all, how to think about God’s plan and, yes, whether we have a purpose, or maybe several.

Starting out as thoughtfully passionate, the play leads us toward the passionately thoughtful, with plenty of profundity. In the first act, a character asked about their feelings will tell everyone what they want them to hear. In the second act, asked how they feel, they stop, think and pretty much pour their hearts out.

Steven Oxman is a theater critic whose work appears in Variety and the Chicago Sun Times.

Winner of eight Pulitzer Prizes, the Chicago Sun-Times was founded in 1948 through a merger of the Chicago Sun and the Daily Times. It’s known for hard-hitting investigative reporting, in-depth political coverage, timely behind-the-scenes sports analysis and insightful entertainment and cultural coverage. In 2022, it became part of the Chicago Public Media family of companies and now operates as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. You can download our latest financial report here.

Become a Member: Support news that's for, from and about Chicago. Invest in journalism that informs and connects. Keep independent local news and information strong in our communities.

Spread the word